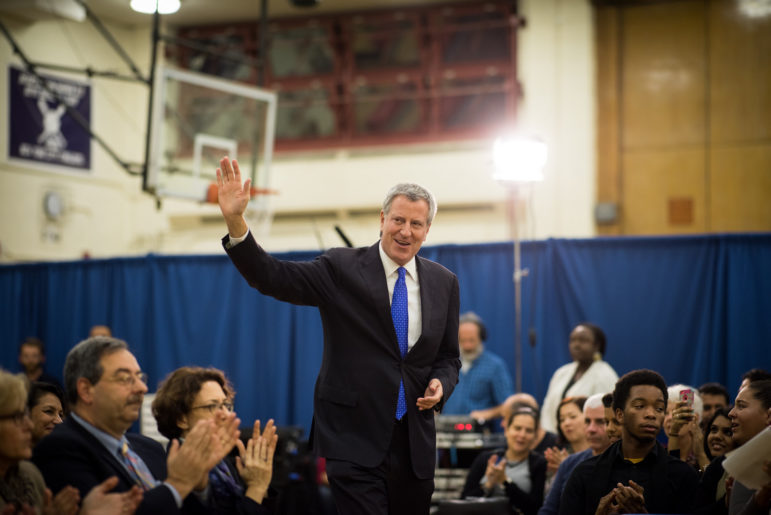

Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photography Office.

The mayor at a town hall meeting in Queens last week.

The 2017 campaign has come and gone in New York City, and while the race for mayor was bereft of suspense, it was not without significance. Mayor Bill de Blasio’s defeat of Republican nominee Nicole Malliotakis and a set of third-party candidates means he is the first Democrat re-elected to City Hall since Ed Koch in 1985 and the first progressive returned to that office since John Lindsay in 1969.

That’s at once an enormous accomplishment as well as a step into the unknown territory of trying to solidify the achievements of his first term while delivering policies that better reflect the progressive ideals the mayor articulates.

Massive tasks await him, like beginning the process of closing Rikers Island, the city’s massive jail complex, and making a real dent in the homeless-shelter population. Huge challenges also loom in Albany, where the mayor’s feud with Governor Andrew Cuomo continues to infect crucial policy discussions, and in Washington, where Republican antipathy to cities—especially “sanctuary” cities—could create genuine crises in coming years. Meanwhile, de Blasio’s ethical lapses and poor relationship with the press threaten to muddy his second term as much as they marred his first.

This story is part of a series on Election 2017 published in partnership with The Nation.

This fall, veteran journalist Juan Gonzalez and respected scholar Joseph Viteritti each published revealing books about de Blasio’s life, his rise to power and the progress—and shortcomings—of his mayoralty. Gonzalez’s book, Reclaiming Gotham: Bill de Blasio and the Movement to End America’s Tale of Two Cities (New Press), situates New York’s mayor within a broader context of progressive ascent in many US cities. The Pragmatist: Bill de Blasio’s Quest to Save the Soul of New York (Oxford), which Viteritti penned, places de Blasio within the historical trajectory of progressive mayors from Fiorello La Guardia to Robert Wagner to Lindsay to the present day.

I sat down with both men on October 24 to talk about de Blasio’s past, present, and future. It’s worth noting that the conversation occurred before de Blasio announced an expansion of his housing plan to 300,000 units over 12 years—a larger version of the plan that, below, Gonzalez criticizes as too small. It’s also important to note that our talk took place before the latest round of revelations about de Blasio’s dealings with the corrupt donor Jona Rechnitz, in which Rechnitz claimed to have been given access to the mayor in exchange for donations he made to de Blasio’s political operation.

Hear the full audio here:

In the text below, the interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jarrett Murphy: You both do a good job of setting de Blasio within a larger context. And Juan, [your book] is looking at him as part of this larger urban progressive movement. What do you think is his role in that?

Juan Gonzalez: Certainly, he’s not the most radical of these progressive mayors. You’d have to look at somebody like Gayle McLaughlin in Richmond, California, or the first Chokwe Lumumba and now the son [in Jackson, Mississippi], or even to some degree Ras Baraka [in Newark]. I think he’s almost sort of in the middle of this progressive movement, ideologically, but because he’s the mayor of the largest city in the country, with the most resources, therefore he has outsized influence in terms of the soapbox that he has. So in that sense, even though he’s not the best example of the progressive mayors, he’s certainly the most influential.

Murphy: And Joe, you talk about de Blasio largely in a historical context going back to La Guardia. And I’m curious—explain how he fits into that tradition.

Joseph Viteritti: Well, he comes along at a very important time, because I feel that, if there’s going to be a serious progressive movement in the country, hopefully it will happen within the Democratic Party—it remains to be seen. But he’s one of the local leaders who, I think, has a real progressive stripe. And what I hope to see him do over the next few years, which I think he will, is become an important voice in terms of the Democratic Party, which is not there yet. I mean, the Democratic Party in 2016 was still very centrist—to their own demise, I believe. And so he’s a very important voice, as Juan said, because he’s the mayor of New York. You know the history of mayors in New York: They’ve always been spokespersons. Lindsay was considered a spokesperson for the American city. La Guardia was in Washington before he got sworn in, saying, “We need housing. We need to deal with this depression that’s going on.” So that’s a very important role for New York City mayors.

Murphy: De Blasio has La Guardia’s desk and, obviously, when he was elected people drew comparisons, friendly or unfriendly, with John Lindsay. To what extent does de Blasio inherit some legacy from those earlier progressive mayors or is there something like a clean slate?

Gonzalez: Well, I think he does have some things in common with La Guardia, including his Italian radical roots. But I think that the advantage that de Blasio had was it wasn’t just him. He had an entire coalition. He had, really, control of the City Council. He had [public advocate] Tish James. He turned [comptroller] Scott Stringer into the most conservative guy in the whole city government, when Scott is really not that conservative. But basically it was a unified government at the local level, so that they were able to get things passed things quickly in the City Council that otherwise might not have happened under La Guardia. Now La Guardia did have a federal government that was behind him. He had the whole new New Deal. But at the local level, he didn’t have the kind of leverage and unified government that de Blasio has.

Viteritti: I see progressivism as a journey. As I’ve said to many people before, my favorite chapter in the book is called “The Soul of New York” and it goes back to La Guardia. Each one contributed something. La Guardia made the case very clearly that government has a stake in taking care of people and that it has an important obligation to take care of people who are struggling. Wagner came along, and Wagner recognized the importance of organized labor. You can’t have a progressive movement without organized labor. But Wagner really couldn’t deal with the very militant racial politics of the ’60s. And that’s something that Lindsay did very well, and I think Lindsay probably worked towards the incorporation of blacks and Latinos in the political process more than any mayor in history. But Lindsay couldn’t get along with organized labor. So you have de Blasio come along, and it’s a very broad coalition. It’s labor. It’s women. It’s minorities. It’s gays and lesbians and transgender people as it’s never been before. So it’s a very broad coalition. And I think it’s part of that journey.

Murphy: I’m wondering if either or both you want to talk about the role of his time in the Dinkins administration in shaping his approach to [being] mayor. Do we see echoes of [that] directly in how he’s governed and how he’s acted as a candidate and mayor?

Gonzalez: What I think de Blasio learned from Dinkins was, one, you’ve got to work. If you want to be mayor, you really have to manage and run the government. And two, I think [there was] the deep lesson that he learned from the way the police department rebelled against Dinkins—the famous riot in City Hall with Giuliani cursing. I’ve always told a lot of the progressive folks who were very angry about de Blasio naming Bratton as police commissioner—they said, “Why would he name Bratton? He’s got all this other baggage”—I said, “Yes, I agree with you. I would not have chosen Bratton. However, I can understand the logic. The logic he had was, I don’t want to happen to me what happened to David Dinkins, which was that the police rebelled.” The police are the army of local government, and if the police are against you, you cannot function. They could allow crime to spiral. So what he decided to do was he would let Bratton—because Bratton was popular with rank-and-file cops and the elite of New York City—Bratton would keep the peace on crime while he got to concentrate on his social agenda.

And it almost didn’t work, because within the first year the police did sort of rebel. But Bratton kept them in line, and kept them from an outright rebellion, like what happened under Dinkins…. So I think that was a strategic decision on his part which I might not have made if I was in his shoes. But I completely understand his reasoning for doing it, because he had been through the thing and he’d seen what happened in Crown Heights and seen what happened in the police riot. And he did not want his first term as mayor to be marred by a constant racial battle with the police.

Murphy: Talking about 2013, de Blasio coming from behind to win the primary without a runoff and to win the general election overwhelmingly. Joe, how much of that do you think is down to what might be described as luck—you know, [Anthony] Weiner imploding, John Liu having the campaign finance board decision against him [in which the board fined Liu $26,000 for campaign-finance violations and denied him public financing]? And how much was it about the wisdom of de Blasio, his skill as a politician and the success of his message?

Viteritti: I think it was a little bit of each. Certainly lucky that Weiner imploded. Certainly lucky that Liu was taken out of the race, though I’m not sure that he was much of a threat. The thing that was impressive about de Blasio’s win was that, other then Liu, he was the only candidate willing to talk about any economic issues and economic inequality—which, unfortunately, Democrats have avoided. And so you had a Democratic primary year and [only] one major candidate willing to talk about it. It was an issue that resonated with people. Christine [Quinn, then the City Council speaker] and Billy [Thompson, the former comptroller] danced around it. They were kind of promising Bloomberg-lite. And he confronted it. He ran against Bloomberg. And that’s one of the significant things about 2013 to me: He demonstrated that this is an issue that has resonance. Unfortunately, Democrats didn’t remember that in 2016.

Murphy: The ’13 race raises the question of where de Blasio’s personal ideological compass actually points. He was the guy who worked for the Quixote Center in the ’80s and ’90s, went to Nicaragua. But then he was Hillary Clinton’s campaign manager [in her 2000 Senate race]. Certainly, he was not the most radical critic of Mayor Bloomberg as a councilmember. How much of the 2013 race and de Blasio’s message was him, the man, and how much was him sensing the moment?

Gonzalez: Well, I think that’s the big problem with Bill de Blasio. He has always had his one foot in each camp. One foot in the activist, dissident camp and one foot in the mainstream Democratic Party camp. And he’s been able to skillfully maneuver between the two to get both to feel that he stands up for their values. And so I think that’s the constant balancing that he’s trying to do. And of course it’s hurt him on some issues. It’s hurt him on the whole “broken windows” stuff with the police. It’s hurt him on housing—on what do you define as affordable housing, and how ambitious, how real is your plan to really deal with the housing crisis in New York? … But I think that his basic ideological compass is far more progressive than most people realize. And I think that he’s always trying to push what he thinks he can get done to achieve a vision—a much, much more progressive vision.

Murphy: Well, Joe, you call your book The Pragmatist, and I think that goes to the fact that there is this tension, right?

Viteritti: Yeah, I see him as a bifurcated personality, pretty much the way Juan just described him: He’s got one foot in both camps. I mean, looking at it realistically, ideology is not enough. You’ve got to go out there and make it work. And so he’s trying to do that. Unlike La Guardia and Lindsay before him, he’s got to count on the private sector for three out of four of his dollars for housing. And so he’s got to do business with them. And they’re not in business for philanthropic reasons. They’re there to make money. And their instinct is to build housing that is more profitable than what we would call “affordable housing.”

Murphy: So de Blasio wins in 2013: 74 percent of the vote. New York City is on the verge of having its most progressive mayor for generations. For each of you personally, what were you worried about for de Blasio?

Viteritti: One of the ironies I see is that, even though I believe he is truly progressive and wants help people who are suffering from inequality, he gets probably his most intense criticism from the left. It’s an irony. And it’s one of the thankless things about being a progressive politician in a city like New York, because progressives, and I’m not criticizing, they’re never satisfied. They’re not going to be satisfied until you solve the problem. And there’s still a lot of people who are not being reached by affordable housing; gentrification thrives. And it’s a very tough position to be in.

Gonzalez: I was worried that he was going to start to double back right away… which he didn’t. The first few months I think were really the critical ones that made me think that this was definitely going to be a new kind of administration. Because they didn’t waste time. They went right after the earned sick pay. They went after [universal] pre-K right away. They went after the settlements on stop-and-frisk right away. Settle the Central Park Five case. I mean, it was one after another—and, of course, the labor contracts. They wasted no time in going right at all of these things. And, as I said in my book, to me, one of the most astonishing wealth transfers was the three years of virtual rent freezes. The reason why the landlords were on TV virtually every night for two years blasting de Blasio is because they lost $2.1 billion in increases that they normally would have gotten if they hadn’t had three years of 1 percent, 0 percent, and 0 percent rent increases….

But then, the other aspect is what’s going on around the country. And I think [for] all of the progressive mayors, the number-one problem they haven’t solved is the affordable-housing problem—which, of course, then merges into the homeless problem, because that’s just another reflection of the same issue of affordable housing. But whether you go to Seattle or Newark or any of these cities, they’re all having the same problem, because the federal government is so completely not involved in affordable housing: “How do I get the private sector to build something that they will never build on their own?”

Murphy: And of course, homelessness here is one problem that has been a minefield for de Blasio, and it’s where his management has been faulted. And one of the major lines of concern about him between the election and inauguration was, is he capable of managing the city? Overall, how do you think he has done with that potential criticism, that potential pitfall?

Viteritti: I don’t see any indications that he’s not a good manager. I mean, to be honest, I don’t think mayors are managers. I think mayors are visionaries who hire managers to manage. Bloomberg had a reputation of being a manager. How much time do you think he spent in the bullpen? So it’s not a management issue to me. I think it’s a visionary issue and it’s a resource issue. And I will come back to kind of reflecting on something Juan wrote more about in his book, which is: What is the future of progressivism without a federal role? Because the primary examples we’ve had of it, under FDR and LBJ, involved the infusion of federal money. And in some ways, New York is not a good test case for the problem now, because New York, fortunately, has a fairly healthy economy. And so [de Blasio’s] able to rely on that. But when you look at some of the other cities that Juan has looked at, they may not have that vibrant local economy that they can count on. It creates real problems for a progressive future. And this is why mayors can’t spend [enough] time in Washington, as far as I’m concerned.

Murphy: At some point, do Trump and Andrew Cuomo put a firm cap on [de Blasio’s] progressive potential locally?

Gonzalez: Where I think the real battleground is going to be—and I think this is why de Blasio is right to support it—is over sanctuary cities. I believe the federal government and the state governments are on a collision course with cities over sanctuary cities. People forget: Eisenhower called federal troops into Little Rock to force the integration of Central High School. John Kennedy called in 2,000 federal marshals to Oxford, Mississippi, to occupy the city for two years to enforce the desegregation of the University of Mississippi. But back then, it was the federal government that was representing the enlightened position and it was the local governments in the south and the state governments that were standing against progress. Now it’s reversed. Now it’s the federal government and the state governments—with the exception of California, because California just recently passed sanctuary status for the entire state. So it’s California and all the cities against the federal government and the rest of the states.

And I believe in places like Texas they’re going start arresting public officials who are refusing to cooperate with ICE and there are going to be direct confrontations between local governments and state and federal government. It will start over sanctuary cities. But there will be conflicts over police-accountability issues, conflicts over sustainable-development issues.

So the fact that you don’t have a majority in the Congress or a majority at the state legislature does not mean you don’t continue to fight for what you think is right. And you create the confrontations, you have teaching moments with the general population and you have more public debate over the justness of these policies. So I think that’s where we’re heading. And de Blasio, when he goes after Trump, I think what he’s doing is setting the terms. This is the battle. It’s us, the cities, against them.

Viteritti: I would add the whole tax issue. I think the mainstream press has been too dismissive of the idea of, let’s raise taxes on the rich. You know, we had a millionaires’ tax. We had a mansion tax. You know who developed the mansion tax? Mario Cuomo. So I think [de Blasio] should continue to talk about it. It’s a very populist issue. And, by the way, I don’t think it’s just a populist issue in New York City. I think it’d be a populist issue in New York State too. Go to Binghamton. People up there are suffering. So issues like that could resonate in New York State.

Murphy: Some of these trends underlie de Blasio’s effort to fashion a national role for himself. And that’s one of the things that the press here has given him a lot of hell over. And in general the press has seemed to me been fairly acrimonious. Does that surprise you?

Viteritti: I’m becoming less and less surprised and more and more disappointed that the mainstream press doesn’t appreciate what he’s trying to do. One of the reasons that he’s not resonating in the Democratic Party the way other progressive mayors have is the Democratic Party doesn’t want to hear what he has to say. La Guardia [worked] with FDR and the Democratic Party; FDR wasn’t progressive on lots of issues, including race, the way he should have been, but, at that point, the Democratic Party was dealing with a national issue that was affecting people across the board whether they were white or black, men or women, and so his message resonated with the mainstream Democrats. LBJ was in Washington when Lindsay was vice-chair of the Kerner Commission [which famously concluded that “Our nation is moving towards two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal”] and became a national spokesperson for cities. And at that point until it changed, the Democratic Party, because of LBJ, was very much focused on cities. He created HUD [the department of Housing and Urban Development] in ’75. And so de Blasio is talking to a very different Democratic Party who’s not ready for his message. To me that makes him even more important.

Gonzalez: I want to get back to the stuff you said before about the journalists, the way they treat de Blasio. I think that journalists, generally speaking, especially journalists in the corporate and commercial media, have become more and more jaded and more and more suspect of people who have ideas. If you have a vision or an ideal, there’s something wrong with you. If you’re in politics, you have to be a maneuverer and practical and respond to pressure and this and that. And I think also because they’re largely of the same milieu of all the people in Manhattan who hate de Blasio, they don’t really get a sense of how the policies are affecting everyday New Yorkers. I mean, the polls! The racial divide in the polls over de Blasio is astounding, considering he’s a white guy. Generally speaking, white people in New York don’t like him and African-Americans and Latinos do. And it’s by wide margins, the difference. And I could see if it was a black candidate, but a white candidate? So I think that it just reflects who is feeling the brunt of the reforms.

Murphy: The ethics concerns about [de Blasio] and his people and their fundraising: Was that purely smoke, or was there some fire there? Does de Blasio have something to answer to progressives for how he conducted himself through those?

Gonzalez: Yeah. I think he—and this is part of him straddling, one foot in one foot out—he has all these people around him who are… some of them are career, you know, fixers. [But] the thing about de Blasio is, why he wasn’t indicted, is because, unfortunately, politics in America is so corrupt that you really have to be caught on videotape saying, “You give me this money and I’ll do this” before you get arrested. I think it became clear that while, there was a lot of sleaziness in some of the stuff that was occurring, first of all—as the prosecutors correctly said—there was no attempt by de Blasio to enrich himself and, two, at every step along the way they consulted lawyers, expert lawyers in campaign finance, who told them, “Yes, as long as you structure it this way, you’re within the law,” so they were following the advice of their lawyers.

But was there a lot of unethical stuff that happened in the de Blasio administration with some of these interest groups? Absolutely. Does it represent some of the worst aspects of American politics? Absolutely. But the reality is that this is happening across the board in most cities in America and most government operations these days.

Viteritti: I mean, my conclusion is, he played by the rules and the rules are dirty.

Murphy: So he’s on the verge of being reelected to a second term. What do you think the second term looks like compared to the first? Will there be some sort of evolution?

Viteritti: You can look at what he’s promised so far. He’s beginning with 3-year-old pre-K. He’s also promised to do some things that are very unpopular. He’s finally ready to close down Rikers Island; [he’s] going to bring jails to your neighborhood. He finally agreed that he’s going to close down cluster-site housing and motels where we put the homeless, and we’re going to bring them to your neighborhood. That’s not a popular thing. It’s very defensible, because I think there’s a support network in people’s neighborhoods that they don’t have when they leave their neighborhoods—and he’s treating them like a service clientele, which is with dignity, rather than as a problem or as a nuisance. But it’s a very bold move on the part of the mayor to announce that on the eve of his election.

And then there’s the uncertainty. Some people talk about, will the economy remain sound? I don’t think it’s going to unravel in the next four years, so that’s probably going to be fine. The big uncertainty is how far will Trump get in winding back even the minor kind of assistance we get from Washington now. If he’s successful in limiting Obamacare, a lot of the cost of health will fall back on state and local governments. If [he] can cut back on housing and education and social services, which [he] wants to do, it’s going to fall on the city, too, so that’s not good news. I mean, that’s a difficult future to look at.

Murphy: What does [de Blasio’s] future hold, do you think?

Gonzalez: I don’t know where he has to go after mayor, because he’s become such a foil of the upstate forces that it would be real tough for him to sell himself in the run for governor. I don’t see that happening. I mean obviously [universal] 3-K is one of them, and some the stuff that you mentioned and also the affordable-housing thing. [But] it’s also not ambitious enough. You know, one of the points I make in my book is that New York had 8.1 million people in 2010. By 2015, you had 8.5 million. The city grew by 375,000 people in five years. That’s the size of an entire city anywhere else in America, just in five years. So even if de Blasio was to implement his 200,000 affordable units over 10 years—forget the fact that they’re not that affordable, it’s that it’s still not enough. Because the city is growing too quickly. So it has to be rethought and somehow deepened. I don’t know what the solution is, but somehow deepened.

And then the other issue is, he’s got to get a successor. Because you don’t want the same thing to happen that happened when you have conservative forces coming back. You have to start really planning who’s the best person to keep the progressive reform movement going.

Murphy

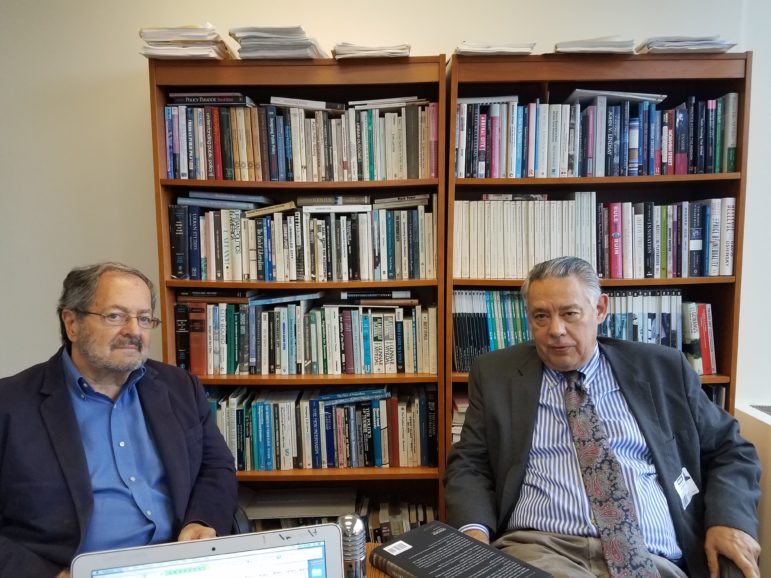

Joseph P. Viteritti, left, is the Thomas Hunter Professor of Public Policy at Hunter College, CUNY, where he is Chair of the Urban Policy and Planning Department. Prior to Hunter, he taught at Princeton, New York University, Harvard, and the State University of New York at Albany. Juan González, right, is one of this country’s best-known Latino journalists. He was a staff columnist for New York’s Daily News from 1987 to 2016 and has been a co-host since 1996 of Democracy Now!

3 thoughts on “The De Blasio Authors Weigh In: Gonzalez and Viteritti on the Mayor’s Past and Future”

I haven’t seen too many councilpersons line up to accept homeless shelters or jails. No neighborhood is going to surrender it’s quality of life to deBlasio.

Well, actually …

http://www.nydailynews.com/news/politics/queens-pols-support-site-new-jail-borough-article-1.3534882

11/51 (21.56%) or 10/51 (19.6%) depending if Crowley wins. Great. Any new jail locations are a long way off. When it gets real and actual locations are being chosen let’s see what happens.