Pam Frederick

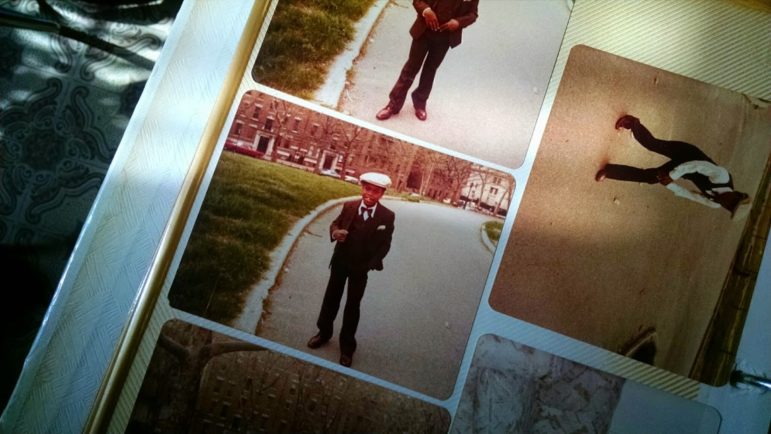

A photo of Carl Van Putten III as a child, displayed by his father, who is now leading a lonely effort to get his son's conviction reconsidered.

The man who shot and killed Orlando Curet was released from prison nearly 15 years ago. The men who confessed to helping him are out, too. Of the five men charged with taking part in the murder, only Carl Van Putten III remains behind bars, still insisting that he had nothing to do with the killing 12 years after a jury found him guilty.

Carl is serving a life sentence for the murder of a drug dealer that took place just steps from his childhood apartment on Hunts Point Avenue. He was the lone holdout when prosecutors offered a reduced sentence to those who were arrested in the killing, claiming that he was not involved in the crime. The decision forced him to forfeit his life, but pleading guilty to a crime he said he did not commit was never an option.

“Your soul is more important than your freedom,” he said during a phone interview from Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary in Pennsylvania.

On August 10, 2004, federal agents met Carl at his parole office and took him into custody. At the time he was 30 years old, and his first child, a son also named Carl Van Putten, was just days old and still in the hospital with his mother.

Carl had been in and out of prison since his first arrest in 1993. But in 2004, by all accounts he had turned his life around. He had been holding down a full-time job for more than a year. He was living with his fiancée in Hunts Point and the two of them had spent the previous months planning for the baby – buying a crib, a bassinet, baby clothes.

For the first time, Carl felt like he had a secure future: a regular job, a woman he loved and a role he had always hoped for – fatherhood.

“I had finally gotten it right,” he said.

Then the brutal past of the South Bronx’s drug epidemic intervened. He had taken part in Curet’s murder nine years earlier, the feds said. The charge, murder while engaged in narcotics conspiracy, and aiding and abetting that crime, would get him a sentence of life without parole after an eight-day trial. And his imprisonment would leave his own aging father bereft, his fiancée alone without his support and his newborn son without a father, like so many children in Hunts Point.

Curet was killed in a dispute over turf. In court documents, the event is recorded like this:

Around 10 p.m. on Oct. 11, 1995, Andrew Lang, a drug dealer who operated out of 754 Manida St., decided to confront Curet, a competing dealer from up the street.

Lang ran a small group of managers, pitchers (or sellers), and lookouts on Manida between Lafayette and Spofford; Curet’s turf was just a half-block away on Lafayette. Lang thought Curet was encroaching on his territory.

Both groups sold cocaine and crack, cooking the crack themselves with water and baking soda in local houses and dealing on the streets and in abandoned buildings. Hardly a block in Hunts Point was spared. Crack came in $2, $3 and $5 bottles or baggies, labeled with different colors to distinguish between dealers.

“On every block there was just people standing on line purchasing all sorts of narcotics. It was, like, all over Hunts Point,” Sgt. Dennis Rodriguez of the Bronx narcotics squad testified at Carl’s trial. “To me it was just out of control.”

That night in October, as Lang and a buddy, Jose “Chubby” Sanchez Echevarria, cruised the neighborhood in Chubby’s car, they spied Curet on the corner of Lafayette and Coster. Lang – unarmed –got out to confront Curet, who in the course of the curbside chat, pulled a revolver from his waistband and positioned it in the pocket of his green army jacket. It’s at this point, Chubby would tell the court, that he put his car in drive and held down the brake. Seconds later, Lang jumped in the passenger-side door headfirst as gunshots blew out the back window and hit the headrests. Chubby peeled out.

Chubby was angered enough by the damage to his car that he told Lang he would subsidize the cost of the hit on Curet. The pair put the word out on the street, and before long, they’d hired Clarence “Boo Boo” Jackson—who worked for the local Bryant Boys operation, another drug crew in the neighborhood—to do the job for $1,000. The deal was made outside the pool hall on Faile and Lafayette, and the guns arrived a short while later in a car driven by Chubby’s brother, Victor.

Word reached the pool hall that Curet was at the bodega up the street on Hunts Point Avenue, just off the corner of Lafayette. So Boo Boo and another shooter, Anthony Ramirez, staked out a position behind the icebox in front of the store. When Curet came out, Boo Boo rushed up behind him and shot him point-blank in the back of the head. Curet landed face down, and Ramirez, also emerging from behind the icebox, put a shot for good measure into Curet’s prone form on the street.

Boo Boo told police and prosecutors this story on three separate occasions—in a hand-written and videotaped confession two weeks after the murder, and again when he was subpoenaed for Carl’s trial in 2005.

But his testimony at the trial didn’t place Carl at the scene of the crime.

While Boo Boo said Carl was given a gun at the pool hall, he told the court he didn’t know where Carl was when the killing team reached the bodega. It was only afterwards, as he and Ramirez headed down Manida Street, that he places Carl back at the scene.

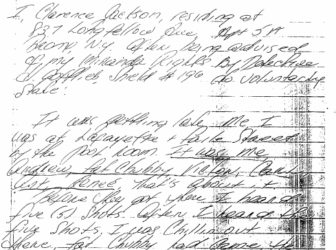

“[Curet] came out of the store, me and Ant went up behind him and just started shooting,” Jackson wrote in a slanted scrawl in his confession. “I ran by his left side and I shot him.”

The other three who confessed to taking part in the murder scheme implicated Carl in the shooting, but they told contradictory stories about where he was and what he did, and even raised questions about whether they were identifying the wrong person. It is the testimony of these four cooperating witnesses – all of whom accepted plea deals in exchange for information on other suspects, and all of whom offered details of the crime that showed “raging inconsistencies,” as Carl’s defense attorney said – that secured Carl’s guilty verdict.

At Carl’s trial, Chubby told the court that Carl emerged from the ice box as a third shooter, contradicting Boo Boo’s confession. But that is not the most striking inconsistency. Chubby, whose car window was shot out that night and started the whole chain of events, said he was living alone by age 13 and was involved with five murders in his career as a drug dealer. When it comes to this murder and Carl’s involvement, he not only told the court that Carl is Latino, but that he had known Carl since the third grade at PS 48 in Hunts Point. But Carl, who is Black, never attended elementary school in Hunts Point; he went to CES 110 near Crotona Park, where he and his father lived until he was in middle school.

Chubby went on to tell the court that he knew Carl from Adlai Stevenson High School in Soundview, but Carl attended Evander Childs High School on Gun Hill Road. Carl’s name also never came up in Sanchez’s previous testimony on the case in 1999, nor when he made a plea deal with the government.

Pablo Colon, who also testified at Carl’s trial, started cooperating with the government in 1999 and met with them over the course of six years, giving up more than a dozen names. He said he saw Carl take one shot, but at the same time, he couldn’t recall the time of year of the murder, and he referred in his testimony not to the ice box but to a pay phone. In two sessions with the government, Colon could not identify Carl in photographs, nor did he know him as a drug dealer.

Fermin San Martin, whose nickname was “Beast” for his violent nature, was one of Carl’s partners in Lang’s dealing operation. He told the court that Carl was behind the ice box with Boo Boo, and describes Carl taking three shots, a scenario that Boo Boo himself does not corroborate. Over the course of years cooperating with the government, he would go on to give information on more than 30 people, reducing his 25-year sentence.

All four men make references in court documents to chances they had to discuss the case – and compare notes – either in prison or before their arrests. Yet not one of their stories matches the other when they testify during Carl’s trial. In each man’s version, Carl is in a different location, or, in the case of the confessed shooter, not there for the shooting at all.

For his part, Carl heard the discussions at the pool hall, and knew something was going on outside – “the streets talk,” he says, and it doesn’t take long for word to spread. As Boo Boo and the crew headed up the hill from the pool hall, he says he and a bunch of other guys ambled over to 52 Park. They then walked up to Lafayette, and by the time they got there, a man was dead on the ground. Carl denies getting a gun at the pool hall.

When cops arrive minutes later, this is what they find: Orlando Curet dead, face-down on the sidewalk, a .22 caliber revolver fully loaded with nine rounds in the waistband of his pants; two discharged shells from 9 millimeter revolver; copper jacketing; a deformed lead bullet.

And when the medical examiner writes her autopsy report a few days later, she notes these details about Curet: He was 34 years old and 5 foot 8, with a blood alcohol level of .24 and a cocaine level of 0.1. He had a gunshot wound near the upper part of the left ear that had been taken at close range, within three and a half feet. He had another bullet in his right leg and a bullet fragment in his chest that likely came from a ricochet. Cause of death: gunshot wound to the head with skull fractures and brain perforation.

For his part, Boo Boo Jackson, facing a life sentence for murder, ends up serving six years after cooperating with the government by providing information on this crime and another, earlier murder. During Carl’s trial in 2005, Carl’s attorney, Bobbi Sternheim, says to Boo Boo when he’s on the stand, “So it was good to get a second chance, correct?”

“By the grace of God,” Jackson answers.

At 84, Carl Van Putten II has one last dream: Before he dies, he wants to get his son, Carl Ellis Van Putten III, out of prison.

The senior Van Putten has seen his share of the world, and of life’s ups and downs. He lived on his own starting at 14, bunking in Harlem and working as a “pin boy” at neighborhood bowling alleys for 12 cents a line. He enlisted in the Army in the first year the U.S. military integrated (“It was 1949, but yes, there was a war going on every night — after supper”). He was married three times, drove a cab for 18 years, still smokes cigarettes without apology (“They are my friend when I need one, my food when I’m hungry, my water when I’m thirsty.”) and by many accounts, has spent the past two decades as one of the more effective civic activists in the South Bronx, leading the charge to create two new waterfront parks in Hunts Point, fight off jail proposals, and start a food pantry at Bright Temple AME Church along with a dozen other neighborhood efforts.

He is a man without regret – a man who remembers his mistakes and his successes with remarkable clarity and equal value; a man who feels he never missed a chance at adventure, at living a life where every day was an opportunity to do or learn something new. He admits now, however, in his ninth decade, things have slowed down for him. He’s come to terms with that. Yet he spends most waking hours thinking if he can accomplish this one last task for his son.

Over the years, Carl Sr. has approached several non-profit legal organizations that work to exonerate the wrongly convicted, as well as dozens of lawyers, to no avail. His last plan now is to simply walk into the U.S. Attorney’s office and ask, man to man, if there’s anything he could do. He’s grasping at straws, but he’s determined and he has a deadline.

“There are few options at this point, that’s what hurts,” says Van Putten. “I can’t let him down. I have to keep trying.”

Carl Sr. raised his son by himself starting at age 6, when the boy’s mother, whose life was overtaken by heroin abuse, could no longer care for him. The two first came to their second-floor apartment on Hunts Point Avenue in 1985.

“My father actually left his wife so he could take care of me,” Carl Jr. says now. “I always feel like I caused him a lot of pain.”

But Carl Sr. sees it differently.

“I was really angry a lot of the time as a younger man, and I didn’t trust anyone or myself for that matter,” Carl Sr. recalls. “Carl saved my life.”

But Carl Sr. worked nights, and Carl Jr. was left to himself in a neighborhood that was rife with the temptation of easy money. Some were able to avoid it, like Carl’s childhood buddy Mario Castro, who to this day is one of his few tethers to the world outside prison.

But that proved too hard for Carl.

“I think he wanted to fit in somehow – he wanted to be popular,” says Castro, who works as a train operator for the MTA and lives in Soundview. “He always wanted more than what he had, but he also had such a big heart.”

Carl headed to Evander Childs High School on Gun Hill Road and would have graduated in 1992, but he didn’t finish senior year. Instead, he started dealing with Andrew Lang.

“It was such a common thing, going to jail,” remembers Castro. “It wasn’t even that big a deal. My goodness, I was the oddball.” Drugs, dealers, addicts, prostitutes — they were all over the place, on corners, in cars, schools, warehouses. Some streets, like Coster where Castro lived, were tamer than others, with mostly families. But walk a block in either direction, he said, and it was “mayhem.”

“It’s unexplainable, really, if you didn’t live it,” says Carl Jr. “Here we are little kids – 11, 12, 13 – and you come home from your little league games and you see hookers practically naked right across the street. You had to walk around them just to get into your apartment.”

The dealers in the neighborhood were kids they grew up with, went to school with, went to parties with. It wasn’t threatening, Castro says now; it was simply familiar.

“The long view is they had choices, but the choices were thin,” says Paul Lipson, who ran teen programs in Hunts Point after college in the late ‘80s and founded The Point Community Development Corporation in 1994. He knew Carl, Boo Boo, Anthony Ramirez and a lot of the others as good kids, who watched out for their younger siblings, who were respectful, thoughtful. “None of these kids were programmed to be bad, but there were absolutely limited prospects. Mix that into the idea that drugs were so pervasive, there’s not much incentive to stop.”

The drug organizations, like Lang’s or the Bryant Boys, were structured like a ladder, with each man getting a bigger cut as he moved up the rungs. The runners (delivery boys) and lookouts were at the bottom. The next rung were the pitchers who sold hand-to-hand, then the managers who supplied the pitchers, and then the head of the local organization, who supplied the whole operation with product, managed the money, the turf, the business.

Sales were brisk, and profits added up quickly, even on the bottom rung. Glassine envelopes of cocaine were sold 10 to a bundle, and 25 bundles in one pack. One pack cost $125, and a manager would keep $25 of that. It wasn’t hard to sell 20 packs in a day, keep $500 and turn the rest in to the stash house.

“I’m not going to say it’s like a business,” Carl says, “but it sure is.”

Carl spent the better part of his 20s on a timeline of arrests, jail time, rehab, rinse, repeat: starting with eight months in Rikers in ’93 for possession and ending in 2003 with a work-release program run out of the now defunct Fulton Correctional Facility across from Crotona Park.

By the time he and Carl were in their late 20s, Castro says he saw a change in him. Carl was holding down his first “legit” job at a discount store in Midtown, he was happy, he wasn’t even thinking about street life, Castro said. Then he was picked up for murder.

“It hit us hard,” said Castro. “It was a total shock.”

The trial was over in eight days.

The only evidence implicating Carl in the murder of Curet was the testimony of those four cooperating witnesses – all of whom had all been convicted of murder or multiple murders, and who had cooperated with the government in order to reduce their own sentences.

Boo Boo Jackson served six years for the murder of Curet and was released in 2001, three years before Carl was even arrested in the case. Chubby Sanchez, the leader of the Hoe Avenue Boys, served 10 years on a reduced sentence for five murders, as well as racketeering and drug charges. He laundered the thousands of dollars he made in the drug trade here in Puerto Rican real-estate, but never had to relinquish any of his properties, according to court documents. Pablo Colon, one of the Bryant Boys, pleaded guilty for conspiracy for two murders and cooperated with the government, and was out for time served – four years – and five years’ probation. Fermin made a deal with the government in 2002 to reduce his 25-year sentence.

With testimony from those four men, yet no material evidence, the jury came back with its decision: guilty.

Hunts Point has the highest prison admissions rate in New York City – 7 out of every 1000 people are imprisoned, according to statistics compiled by the Justice Mapping Center. Of those in prison, nearly all – more than 90 percent – are men. Add that to a neighborhood where nearly half the households are run by single parents, and the strain on families begins to show.

When Carl was arrested in 2004, his girlfriend and new born son – just days old – were still in the hospital. His father carried the boy home from the hospital the day after Carl’s arrest.

“It isn’t just one person, it’s a whole family that’s affected,” says Carl Sr. “There are a lot of other people who are also serving a sentence.”

In 2007, Carl was assigned a lawyer to appeal his conviction. Brian Sheppard, who has a private practice on Long Island, argued two main points in his more than 90 pages of briefs to the court: that the judge improperly instructed the jury on the law regarding the charges against Carl, resulting in a guilty verdict; and that Carl’s sentence of life without parole was unfair, especially when compared to the lighter sentences received by all of the other defendants charged in the case.

Federal sentencing guidelines established in 1984 allow the judge to choose from within a range of sentences based on the crime, which is then influenced by the defendant’s prior record. But in 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the guidelines are advisory only – the judge can aim above or below. In Carl’s case, the judge chose the sentence recommended by the guidelines—life in prison without the possibility of parole—despite the various mitigating factors that Sheppard cited in his appellate briefs, including the disparity between Carl’s sentence and that of the others’ charged in the case, and the fact that Carl had completely turned his life around before his arrest in this case nine years after the crime was committed.

It is Sheppard’s firm belief that if Carl had pleaded guilty—as did everyone else charged in the case—he would not have received a life sentence. More than 95 percent of federal criminal cases result in plea bargains, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Often it’s the innocent ones, Sheppard says, who get the longer sentences because they refuse to plead guilty to a crime they did not commit.

“This was one of the most extreme cases you could imagine,” says Sheppard now, 10 years after he argued the case. “He’s probably innocent of the crime for which he was convicted, but he’s in for life, he’ll never get out, and most of the people in the case who were guilty are now out, walking around, because they pled guilty and in some instances, because they testified against Carl.”

The U.S. Court of Appeals confirmed Carl’s conviction in 2008, and at that time, his sentence was vacated and his case was remanded to the district court, with a reminder to the court that it had the “discretion to deviate from a guidelines sentence.” Carl was resentenced to the original life sentence a year later.

Carl’s case was one in a substantial string of Sheppard’s criminal cases in which the appeals court rendered decisions that, he believes, were clearly wrong on the law, the facts, or both. Largely for that reason, Sheppard stopped taking assignments from the court, and has instead focused on writing a book to enlighten the public about what he calls “systemic causes of wrongful convictions which have not received proper attention.”

“Carl’s was one of those cases that sort of pushed me over the edge,” Sheppard says now. “I finally asked, ‘What am I doing here?’ It’s an exercise in futility.”

By his count, Carl Jr. has read hundreds of books in his decade behind bars. “I think I have seen every Dean Koontz and James Patterson book there is,” he says, referring to the best-selling paperback writers. The days repeat in an endless loop, like in Bill Murray’s movie “Groundhog Day,” he says. He’s 43 years old; he’s been in prison for 12 years. “My life is just a small shell. It’s all the same.”

Carl has also tried to take legal matters into his own hands, and this past September, filed a “successive or second motion to vacate” to the Court of Appeals. The 26-page motion sites case law to claim that he is being held unlawfully, and “sentenced without authority of law.” His sentence was vacated once before, at his appeal, but reinstated. Still, it has given him some glimmer of hope, and he has family and friends on the outside shopping his argument around to any lawyer who will answer a call or respond to an email. And Carl Sr. continues to reach out to pro-bono legal organizations as well as exoneration groups across the country, hoping someone will offer their support.

Pam Frederick

Carl's father and son (both also named Carl Van Putten) at a recent prison visit.

At Lewisburg, the federal prison in Pennsylvania where Carl has spent the past five years, mornings start early, with 5:30 wake up and out of the cell by 6. Carl is one of the lucky ones – he is in a smaller unit for prisoners with good behavior and he has a work assignment on the painting crew that pays him $9 a month. If you work your way up the ladder, you can collect as much as $40 a month to spend on calls and emails, toiletries or microwavable food.

“It’s not a good place to imagine – and TV doesn’t do it justice,” Carl says. “But I’m thankful for every day I wake up.”

The rest of the night – from 3:15 until lights out at 10 – is just killing time. Reading. Listening to games on WFAN. There are six or seven TVs tuned to mostly sports channels, as well as bible study classes, accounting classes, some yard time. Carl sticks to himself. Prison life is tribal, Carl says, clearly divided by race. “It is totally a different world,” he says from the prison pay phones. “I don’t know how I’ve done 11 years – I don’t know how I’ve managed.”

Ultimately, it’s not the tedium that tortures him. It’s the knowledge that inside, he is powerless. That life goes on without him on the outside. That things happen to his family, to his son, to his father, that he can’t help or change.

On a Sunday in November last year, Carl Jr. was one of only three prisoners to receive visitors in the large and sterile visiting room at The Big House, as it’s called on the guards’ navy blue custom hoodies. Set up with 20 or so laminate tables — a chair on one side for prisoners, two chairs on the other for visitors – the room is unremarkable except for the view of the 6′ x 6′ prison yard cages reserved for guys in solitary, visible only by peeking through the slats in the plastic venetian blinds.

His 10-year-old son, Carl Aquan Ellis Van Putten IV, or little Carl, hangs on his father’s shoulders while his grandfather watches. The boy leans against his father’s broad back –at 5’9″ he’s well over 200 pounds – rubs his head, inspects his ears, his biceps, his tattoos. On one forearm is a fading likeness of Carl III as a baby – all eyes. This is a father he has only seen twice before, and both times in the Lewisburg visiting room.

The two play checkers for a full two hours (dad wins) with crosstalk going between father and son, grandfather and grandson. The scene is casual, comfortable, as if the three of them hang out here every Sunday. There’s no obvious explanation for their familiarity; the grandfather credits his daughter-in-law for keeping Carl Jr. alive in the mind of his grandson, keeping pictures in the house, talking about him, keeping in touch for all these years he’s been “inside.” But to watch the father and son is to see two people with no pretense, no awkward moments, no discomfort. These two are far from strangers to each other, though they have spent less than five hours together in their lives.

“Do you have any friends?” little Carl asks his father.

“No, not in here.”

“Not any?”

“I don’t try to make friends in here. It’s best that way.”

Carl Jr. says he dreams about being with his son and his father on the outside, together, the three of them. He’s only done that twice in his life, in the summer of 2014 and fall 2015, both times at Lewisburg. And he dreams of the Yankees, or rather, the dream of having the freedom and the leisure of walking to the stadium, grabbing tickets, watching the ballgame.

When Carl looks back on his life just before he was arrested, he goes back to one moment that in its retelling, sort of shimmers. It’s one of those all-is-right-with-the-world moments that rarely come in life, but when they do, they stick.

He had left his job in Midtown early to catch the 1:07 game at Yankee Stadium. A self-described sports fanatic, he would catch as many as 30 Yankee games a season, sometimes with friends or, if not, happy to be by himself, on the third base side if given the choice. In early July 2004, the Yankees were in a home stand with Detroit, and during the Tuesday night game, the AL star Dmitri Young had posted three doubles. Carl caught the Wednesday afternoon game, and Young was up at bat when the feeling came over him. He was living with a woman he loved, his son’s birth was just a month away, he had steady work.

“I was thinking that I wasn’t looking over my shoulder, that I was working, that I was –” he pauses in the retelling. “I was just happy. I dream about that.”

5 thoughts on “Despite Shaky Testimony, Bronx Man Serving Life for ’95 Murder”

My name is Mark Sanchez and I as well grew up with Carl he actually lived right across from me in a split tenement building devided by a court yard since he moved to Hunts Point ave he spend endless nights over my house and I visited his house we were young and carefree Carl is considered Family to me and I love him dearly I as well know all thee other parties involved in this crime Carl was convicted of and know in my heart that Carl is innocent of this Crime Carl is a great person and has a great heart he was the fall guy for this crime and there is a huge injustice taking place that really needs to be looked at and reconsidered

Carl is a very humble person, who couldn’t hurt a fly. Him being in prison for a crime he clearly did not commit is wrong. There’s NO JUSTICE for this man. The people who were on this case ALL have their FREEDOM except Carl. So UNFAIR. The system is UNFAIR They threaten to put Carl in prison for not testifying against his friends. The SAME friends testified against him , and put him in PRISON. Such a sad situation. JUSTICE for CARL VAN PUTTEN

in this article it reads that only Carl’s family has suffered what about the family of Orlando Curet that man was killed in cold blood and Carl was mighty close to the murder if he was on Lafayette who to say he wasnt involved him when 3 other testified it was him why bring up his name if he had nothing to do with it your name dont get mention in a murder charge for no reason 3 people dont say your name for no reason you ain’t gonna get arrested 15 years later with no evidence if he in there its cause he had a hand in it in some shape or form do I feel sorry for him no i feel sorry for his son having to live with out a father over stupidity a piece of land that dont even belong to them it belongs to the city of New York a man was taken from his family from this earth over turf something everybody lossed when they went in and the other men only doing 6 and 10 year and whatever the other one got that’s it for murder that is what taken a life is worth then we wonder why some many people are killing other people you only got to do 6 year if you snitch crazy

Nancyvelez1119@yahoo.com

Justice

Where is The justice For my brother Orlando Curet.

Why haven’t we been contacted so

people could hear the other side of the story’.

I know everybody in this case even the victim we called him him Pete or Vampiro. He was a OG who was trying to take over 1275 after Ricardo & his wife. Maine being young but ol skool had mad respect for Pete but Pete didn’t want to respect the new generation. He was trying to shut Maine down & when Maine approached him respectfully Pete shot him. That started everything. If you his sister you know this is true & you also know Pete was so gangsta that he wouldn’t want anybody cooperating wit police to lock up who ever murdered him. Pete was 100% street and lived and died by that code. Pete’s mistake was not taking Maine seriously letting him live. He didn’t kill Maine that day because he just wanted to scare him. Big mistake. Everybody knew Pete in the hood 7 knew he bussed his gun. He thought his rep would scare the youngins away and it backfired. Same mistake Chuito made. However what you be calling for justice if it was the other way around? I know Carl & i won’t get into all the details, but Carl wasn’t there the moment Boo killed Pete.

The truth is that this drug game is the cancer we should all be standing against. The people who killed Pete knew Pete from childhood. He knew their parents, aunts, uncles etcetera and saw them all grow up. The greed & treachery of the drug game tore them apart as well as many other people in the Point and hoods all over. Chuito was murdered by kids who not only did he see grow up, but he literally caught a body with their cousin Peechy ten years earlier. Mamita & Felo got murdered by a crackhead who Mamita took care of his whole family and the hit was put out by one of Mamita’s son’s close friends. Little Lou and Billy were set up by dudes they not only grew up with but their parents grew up with each other and there are so many others. Besides, your brother got a couple of bodies with him. You gotta call for justice for them too right?