Nearly four decades ago, Ellen Baxter and I set out to document the predicament of New York’s street-dwelling poor. Released in 1981, Private Lives / Public Spaces confirmed what was already open secret: the city’s emergency shelter system was failing badly. With the signing of the Callahan consent decree later that year, separate litigation filed on behalf of homeless families, extensive media coverage and mounting public support, real reform seemed in the works. But the scandal of the street was just a sentinel event. Deeper mischief was afoot.

Since then, five mayors, five governors and a slew of commissioners have grappled with framing homelessness, targeting and funding solutions, and managing the political fallout. None has been better prepared or more committed than the current administration. So it’s an unwelcome task to report that scrambling for shelter seems destined to become part of the survival kit of New York’s poor.

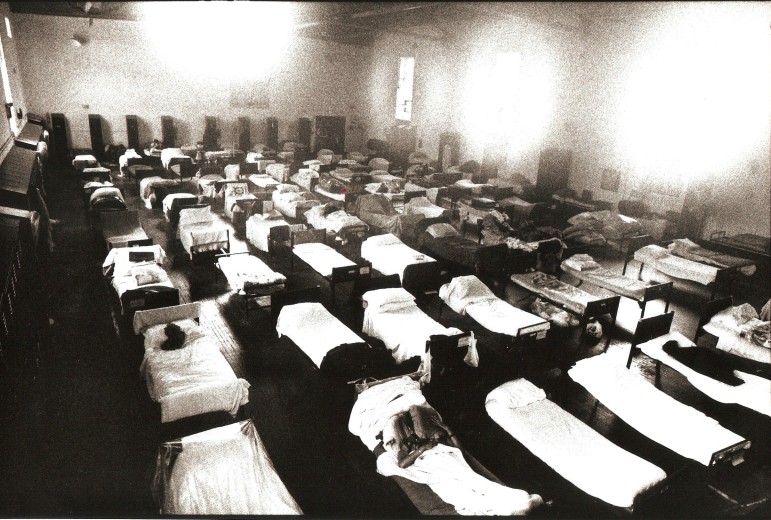

In the early 1980s, legal advocacy framed homelessness as an elemental right denied, but the public was pointed elsewhere for guidance. A “vagrancy crisis” was declared at a time when a mayoral advisor confided to us that exposure-related street deaths were commonplace. The New York Times christened its home base “the new Calcutta.” A state judge called shelter conditions “Hogarthian.” The new homeless were an historical anomaly, dangerous, a poor apart, something that didn’t belong.

But make no mistake: then and today, the dystopian scenes we see are neither third world makeovers nor Dickensian-era extensions. They are our own fresh hell.

Don’t be misled by recurring motifs in press coverage—city/state feuding, the singularity of New York’s right to shelter, reliance on profit-making flophouses (renamed “three-quarters housing”), the carping of advocates and defensiveness of officials. The underlying problem has morphed decisively. The surface evidence is the shelter census, which has surged from roughly 1,200 beds for singles and a few score for families then, to 60,000 plus today. But new forces of displacement are driving this demand and determining the load that shelter is supposed to shoulder.

By now, those forces have been well rehearsed. Deindustrialization, gentrification and neoliberal stringency—code words for structural forces behind what geologists might call “induced seismicity” in bedrock housing—took shape in the 1980s and have accelerated since then. Widespread residential instability, due largely to insupportable rent burden, has become the bass line of urban poverty. Episodic displacement is its inevitable accompaniment. Whether expressed as serial evictions, ever-shifting circuits of makeshift arrangements testing kith and kin alike, ill-planned institutional exits (from corrections, detox, mental health or foster care), or intolerable cohabitation (intimate partner violence): precarious housing is the new normal. Shelter—scorned skid row afterthought—is now its would-be failsafe.

Sensible homelessness policy is so elusive because shelter has been pressed into service as the last resort for the fallout from all those institutional and market failures. Running a bare-bones emergency effort located far downstream, relief officials can do little to correct short-sighted policy and economic dislocation upstream. This works decently enough with a humming economy, robust kinship networks and a backlog of cheap housing. In postwar years, the shelter bureau subsidized a seedy retirement community (the Bowery) and put up families displaced by fire or vacate orders. But not today.

Advocates argue that shelter should be a buffer, a last dignity-shielding redoubt, not a degrading penalty for failure to plan or cope. In a weak welfare state, it will probably never be that. But we can commit to making it a decent way-station, not a grim terminus. Better still would be targeting resources where they can do the most good—in prevention.

Refreshingly, the city now seems to get this. Even as federal and state authorities dither in well-founded fear of failure, the de Blasio administration has committed itself to forging a homelessness policy tuned to the complexities of our troubled times. Nettlesome critic recruited as put-up-or-shut-up bureaucrat, Steve Banks emerged as its point person. In short order, eviction prevention and rent-subsidy programs were beefed up, while new multi-agency efforts were undertaken to repair a dysfunctional shelter system suffering decades of systemic neglect.

But the necessary complement to temporary shelter is affordable housing. Here the math is more revealing than the messaging. Recent research by the Citizens Budget Commission estimates the number of “severely rent burdened” (paying more than 50 percent of income on rent) households in specific income groups. “Extremely low income” (<$25,150 for a family of four) households are estimated at 246,000; “very low income” ($25,150 – $41,950), at 133,000. For these 379,000 precariously pitched households, the mayor’s affordable housing plan reserves a total of 40,000 units over 10 years. Even if we credit the plan with full success (which makes some magical realist assumptions about federal support), and assume no increase in the numbers of those in dire need (unlikely), the plan will be good news for just over 10 percent of sorely strapped households.

So there’s no evading this awkward truth: Whether as prevention, deterrence or respite, the shelter system will continue to anchor and belay the housing struggles of low-income New Yorkers. What was once a rude salvage operation targeting the disreputable poor is now an integral part of how those disfavored by fortune get by.

In such an environment, it’s folly to subscribe to “disparate missions” for housing and homelessness divisions within city government. It’s cynical for the state to play coy. Intensified preventive efforts and set-asides in existing housing will surely help; so would more rational institutional placement. But without a serious reckoning with what it will take to integrate affordable housing and shelter policy in the long run—and a significantly greater commitment from the city and state to creating housing affordable for those earning 30 percent of area median income or less—the specter of enduring mass homelessness will continue to haunt New York.

But if we can’t “build our way out of” this crisis, there is promising news on a parallel front. The “Housing Stability Support” policy being developed by State Assemblymember Andrew Hevesi draws upon the demonstrable success of a host of targeted (if often time-limited) rental subsidy programs, programs that have operated at varying degrees of visibility. Left to its own devices, of course, the private market is an inconstant partner. But the focus on enhanced demand (rental subsidies to be used in existing housing), in addition to expanded supply (developing affordable units as contingent “set asides”), is a welcome one. The devil, as always, will reside in the details.

One thought on “CityViews: The Long View on New York’s Homeless Problem”

We don’t need affordable housing as much as we need plain old cheap housing. We need a massive influx of net new housing created, and the transit/infrastructure corridors to support it. We need lots of upzoning among new corridors, and we need to further develop our non-Manhattan CBDs. The city needs to grow, even if it means property owners don’t benefit from value accrual so richly as they have overall in the past 25 years. We need to acknowledge that a static or slightly sloping housing cost trend is not a calamity for the greater city. Real estate interests have colored all the language around this. Everything that is not exceeding inflation is a ‘collapse’. But they do not have the best interests of the whole city, and should not be allowed to talk like they do.