NYCCFB

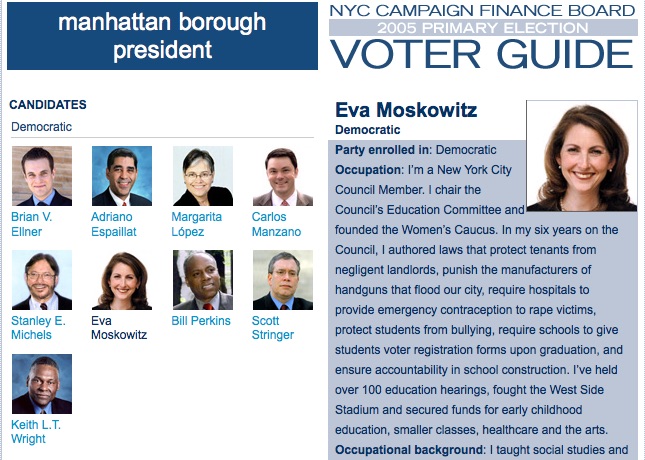

From the Campaign Finance Board's 2005 voters' guide.

Eva Moskowitz on Thursday said she wouldn’t re-enter political life with a run for mayor in 2017. Mere moments after she dropped the news, the city’s Campaign Finance Board released a decision that in some ways echoed a dispute in Moskowitz’s last race.

In 2005, Moskowitz and Comptroller Scott Stringer were the leading candidates in a nine-person Democratic primary for Manhattan borough president. Then-Assemblyman Stringer won it with 26 percent of the vote to the second-place Moskowitz, a councilwoman at the time, who netted 17 percent. The result put both leaders on the paths they now tread. Stringer was re-elected to the borough post in 2009 and beat former governor Eliot Spitzer to become comptroller in 2013. Moskowitz left public office to found Success Academies and become a luminary of (and lightning rod in) the charter-school movement.

That 2005 contest has an even broader legacy, however — one that could shape the next race for mayor even if Moskowitz stays on the sidelines.

Late in that campaign, Moskowitz complained to the city’s Campaign Finance Board that the Working Families Party, which sent out mailers attacking Moskowitz, was coordinating with Stringer’s operation. Under the city’s campaign finance law, candidates are limited in the size of donations they can receive and, if they accept public financing as most candidates do, in what they can spend. A way to cheat that system would be to set up an independent apparatus that could raise and spend extra money on your behalf. So the CFB mandates that independent efforts by unions, PACs or others actually be independent—with no coordination between them and candidates’ campaigns.

On its face it’s a simple rule, but it leaves a complex problem for campaign finance regulators and watchdogs: What if a candidate doesn’t need to whisper instructions to his adoring PACs? What if the strategy is so obvious, and the targets so clear, that no coordination is necessary? Even if the coordination rule is obeyed, the spirit of the campaign finance laws—whose aim is to create a level playing field and reduce the influence of money on politics—can be undermined.

Nearly three years after the 2005 primary concluded, the CFB determined that Stringer and the Working Families Party had not violated the rule, though Stringer was fined for other lapses in compliance with the law. The Board has since issued three advisory opinions (in 2009, 2012 and 2013) to clarify what the “no coordination” rule means.

On Thursday, the CFB announced that it would the fine The Advance Group, a major political consulting firm, $15,000 for coordinating the activities of NYCLASS, the animal-rights group that was so visible in the 2013 campaign, and two of the City Council campaigns that Advance was working for. “This substantial penalty sends a clear message that the Campaign Finance Board will vigorously enforce coordination between outside groups and candidates that violates the law. These violations strike at the very heart of our campaign finance program. When a consultant’s actions make it impossible for their clients to comply with the law, the Board will hold the consultant accountable,” the board said in a statement.

On all levels of government, independent expenditures—think Super PACs—are today’s chief worry for those trying to reduce the power of money at the ballot box. Regardless of who runs for mayor, the city’s own rules on outside money are likely to be tested in 2017. Moskowitz’s well-funded allies in the charter-school movement have already displayed a penchant for putting tough, anti-de Blasio ads on the air and in the mail, and that’s likely to continue no matter who runs against the mayor. If such an air war breaks out, de Blasio’s supporters in the city’s unions are unlikely to sit on the sidelines, either.