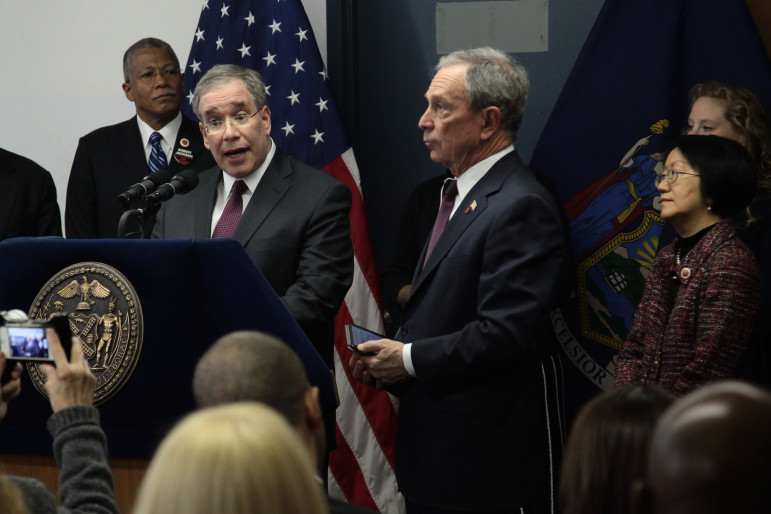

Office of the Mayor/Edward Reed

Then-Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer, seen with Mayor Bloomberg in a 2013 photo. As comptroller, Stringer has advanced a transparency initiative that began during the Bloomberg years.

The hidden contracting world that’s existed underneath the day-to-day business of the City of New York is finally being uncovered.

On Tuesday afternoon, Comptroller Scott Stringer announced that Checkbook NYC, which tracks how the city spends its money and who it gives it to, now includes some data on subcontracts, with more to come.

That boring, boring word, “subcontract,” has the power to put even the wonkiest reader to sleep. But subcontracting data is the gold standard for government transparency and this new system has been in the works at City Hall for at least a decade.

It’s a really big deal—a landmark achievement for government transparency in America. Government accountability advocates are starting to buzz about it.

“There’s no blueprint for this. No state or locality in the U.S. is reporting subcontracts online. Zero. This is a national first,” said Reinvent Albany’s John Kaehny, co-chair of the New York City Transparency Working Group.

Every year, the City of New York pays billions to private companies to do work. And every year, those companies in turn pay out hundreds of millions — sometimes more than $1 billion — to other companies to actually do the work. Forever, those second-hand companies have cashed taxpayer checks in anonymity. The obscurity has been especially troubling to efforts to pin down whether the city was making any progress at letting minority- and women-owned businesses (or MWBE) a fair shot at lucrative city deals.

“The public can now see in real time where money is flowing at all levels of contracting in one place. These new features will provide transparency about MWBE spending as never before and also give crucial insight into how contracts are distributed once they are awarded,” Stringer said in a press release.

But the transparency will not merely benefit those outside government. Amazingly, this will be the first time the city itself can view this information in one place. Until now, a subcontractor could be doing millions in work for a dozen different agencies and there was no central system to track it all. That made preventing fraud difficult.

The implications of Stringer’s move are far-reaching. The “sub” prefix is misleading because subcontractors could be doing more work than some of the bigger prime vendors in the city. They could be huge campaign donors. Or big, local prime vendors could be outsourcing a majority of a job to Nebraska or even India.

Creating this system dates back to at least 2005 when then-Chief Procurement Officer of New York City Marla Simpson told the Council that the administration was working on building an electronic system to track subcontractors. It wasn’t until after the CityTime scandal — where subcontractor Technodyne, a city-certified minority-owned business, milked millions from the city — that the Bloomberg administration moved on the issue.

On a Tuesday in March 2013, Mayor Bloomberg and Comptroller John Liu announced they had been working on creating of a new reporting system for subcontractors. Not one daily newspaper in New York reported the announcement. If the administration was trying to make the announcement fly under the radar, it picked its spot well: The stop-and-frisk trial was in its second day, Council speaker and mayoral frontrunner Christine Quinn announced she supported a bill to create an inspector general for the NYPD and many papers were still in soda-ban craze.

Beyond uncomfortable reminders of CityTime, the new tracking system also raised awkward questions like: What was the city doing before this? A city employee speaking on the condition of anonymity to City Limits back in 2013 said that for years, every city agency had its own process for reporting payments from primes to subs. Some contractors even reported what they paid to their subcontractors (sometimes millions of dollars) by filling out forms by hand.

The room for error was so great that Liu’s office refused to trust any subcontracting dollars for its M/WBE report card. When Stringer’s office picked up the pieces in early 2014, it realized the subcontracting data was so intertwined with the M/WBE data that it had to overhaul its M/WBE report before releasing the subcontracting data.

In the coming months, and years, this new data stream will allow the public, researchers, data scientists and journalists to follow the money like they never have before—and maybe find some loose change along the way.

2 thoughts on “City Boosts Transparency on Millions in Spending”

There is more MWBE corruption if you look into how Empire State Development runs their MWBE Division. Keep on investigating the lack of transparency on the state level.

Pingback: What’s Brewing? This Week’s Must Read Link Roundup | The BQ Brew