Marguerite Ward

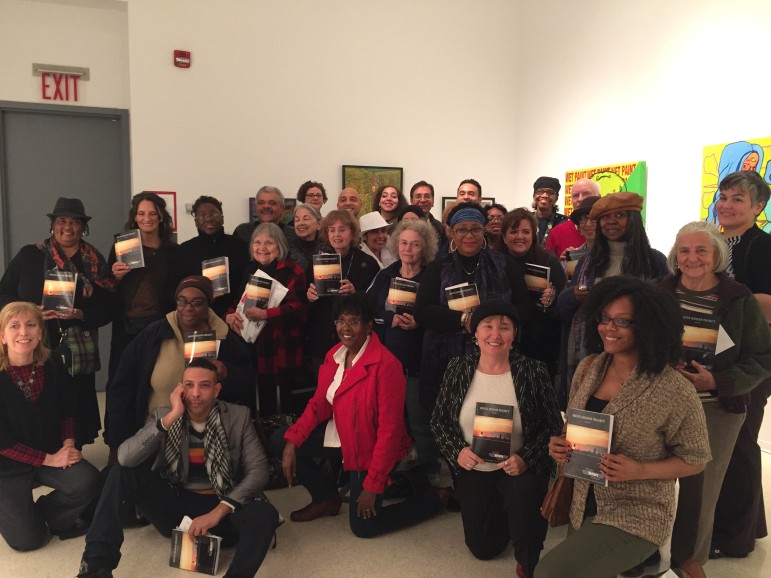

Authors of a volume of Bronx memoirs pose at a recent book launch event. The project challenges stereotypes about the borough.

It was early morning New Year’s Day in 1999, when Orlando Ferrand, a resident of Manhattan at the time, hopped on a subway train headed toward the Bronx. He was heavily intoxicated after a night of partying and had no reason to be headed there.

When he woke up, he was at the Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx. He had overdosed and nearly died.

“Somebody saved my life here in the Bronx, in Jacobi Hospital. I took that as a sign,” Ferrand said.

Shortly after the near-death experience, he moved to the Bronx to start a new life. “I love the area. I feel and have always felt that the Bronx is a very unique space,” Ferrand said.

For Ferrand, a 47-year-old writer and teacher living in Pelham Parkway, the “Bronx Memoir Project – Volume 1” was a chance to share his very personal story of arriving in the Bronx. His is one of approximately fifty stories published on Dec. 3, as part of The Bronx Writer’s Center’s creative memoir project.

“We’re trying to dispel the mythology about what the Bronx is or does. It’s a groundbreaking thing to have people tell their own stories as opposed to folks talking about us,” said Deirdre Scott, executive director of the Bronx Council on the Arts.

The book shares more than fifty short stories, including an account of Nazi Germany’s invasion of Italy during World War II, a snapshot of the South Bronx in the 1950s and a story of what it was like working alongside Alvin Ailey and Nipsey Russell in the Harlem cabaret scene of the 50s and 60s.

The Bronx Writers Center, a subset of the Bronx Council on the Arts, produced and published the memoir project. The center hosted a series of public writing workshops and had an open call for submissions to solicit resident stories.

Sonia Fuentes is a 63-year-old retired city school principal who has lived in the Bronx her entire life. In her memoir (which you can read below), Fuentes walks readers through what the borough was like in the 1950’s.

Ersilia Zaccaro Crawford, an 81-year-old resident of Co-op City, published three short memoir pieces in the book after attending one of the public writing workshops.

“My stories are about my childhood in Italy during WWII. I feel very proud about it, to be able to share them,” Crawford, who has lived in the Bronx for some 45 years, said.

Other stories in the book provide a more recent snapshot of the borough. Siri Nelson, a 29-year-old resident in Fordham and student at the College of New Rochelle, shared her story about meeting someone from OkCupid, an online dating side, in person. While the date didn’t pan out, she was happy to discover a new area of the Bronx.

“I walked away with a sense of satisfaction. At least now I knew about Arthur Avenue,” said Nelson, reading her story at the Bronx Council on the Arts’ book launch party last week.

Laurie Humpel, a 32-year-old resident of Bedford Park and an author of a story in the book, said that the book was a way for Bronx residents to have their voice be heard.

“People have a lot of things to say about the Bronx and it’s usually negative. To have Bronx residents put their own spin on things, it’s nice,” Humpel said.

The project was funded by the National Endowment for the Arts, the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs, NYS Council on the Arts, the Lambent Foundation Fund of the Tides Foundation, The Joan Mitchell Foundation, Lily Auchincloss Foundation, Inc., Councilman James Vacca and the Bronx Delegation of the City Council.

“I love how the stories came together. The diversity of richness is amazing,” said Charlie Vásquez, director of the Bronx Writers Center.

Vásquez said the organization hopes to publish a second volume of the project.

“The Kelly Street I Knew”

by Sonia Fuentes Resto

The deafening roar of the IRT elevated train as it entered the Intervale Avenue Station rested for a brief moment before introducing the quieter sound of the subway doors opening, then quickly closing. On weekdays, these sounds were repeated every half hour.

At the age of six I was accustomed to the rumble of the trains from the proximity of our fourth floor window. I enjoyed watching the riders entering or exiting the cars, always in a rush.

I often wondered, “Why are they running? Where are they going?”

On special occasions, my parents would take me up those steep train station stairs to ride the magnificent iron monster for a ride “downtown.”

Oh, what a treat that was! Going to see the skyscrapers or Radio City Music Hall in Manhattan was an event that made an everlasting impression on me.

Living on Kelly Street in the Bronx during the early 1950s was very convenient for my family. Titi Anita, my aunt, lived on the next block over, on a magically curved street known as “Banana Kelly”.

Tío Pepe lived on Simpson Street and Titi Tona lived on Prospect Avenue, both just a subway stop away. On the corner of Kelly Street and Westchester Avenue, just a few steps from our building, were the local friendly farmacia, bodega, and the family doctor’s office.

On that same avenue was el vivero, the live poultry slaughterhouse I dreaded visiting. The acrid smell of wet feathers and the helpless squawking of the fowl as they were held against the large shaving machines were overwhelming for the animal lover in me. I was never able to witness the actual slaughtering process, since I feigned illness whenever my abuela encouraged me to watch.

She thought my behavior was childish because she slaughtered chickens often as a young girl. The workers at the poultry place recognized my terror and always offered a balloon as consolation. To this day, I associate balloons with the butchering of chickens. However, once the fowl was in a pot with Puerto Rican spices and herbs like adobo, cilantro, and fresh garlic, and stewed to perfection at home, I delighted in savoring my favorite pieces.

My family lived at 971 Kelly Street when I was born in 1951. The beige limestone four-story building had twenty apartments. We lived in 1D, a two-bedroom apartment for my parents, grandmother, two brothers, my baby sister and me.

My parents were close friends with the families that lived in apartments 2D, 3D, 1C, and 4E. All other neighbors in that building were known to us by name. Most of them had extended families living with them or close by. There were few single parent families, and everyone seemed to have a job.

The hallways, front stoops, and back stairs were always immaculate and people never loitered. I cannot remember a time when any of the residents of the other small buildings on Kelly Street “hung out” in the front stoops for extended periods of time. Everyone remained indoors for the most part, even during the sweltering heat of New York summers.

My mother was a beautician and made house calls whenever she wasn’t working at her own salon. One of her favorite clients lived two buildings away from us on the fifth floor. In order to avoid going down four flights of stairs and then climbing another five flights to service her friend, my mother had a special plan.

She would take my sister and I with her when she went up to the roof of our building. She would jump across the adjacent roof edges to the adjoining building, extending her protective arms for us to do the same. There was such tranquility and silence up there.

The tar was always soft and smelled like a brand new doll.

I recall my excitement of being up so high and able to see Kelly Street below, which seemed miles away. I was always excited about these adventures, because to a seven-year-old, it felt like flying.

On Saturday mornings my father washed and waxed the linoleum floors in our apartment. The smell of King Pine gave us a sense of renewal and cleanliness. At the same time the Victrola played Mantovani’s The Soul of Spain at full volume.

I would shadow dance to the toreador’s entrance music to the bullfighter’s arena. By the afternoon hours, my father was dressed to the nines with his suit, tie and fedora hat. Most men wore felt fedoras every day even with casual clothes. In the winter they wore long coats and white silk scarves in the style of Argentinian tango sensation, Carlos Gardel.

For special occasions, women always wore dresses, stockings and high heels. Fancy hairstyles, long necklaces, and dark red lipstick were a must. Every family picture I have from that era is testimony to this fact. No Puerto Rican woman ever dared to wear slacks during those years.

Saturday nights were times of celebration. On special Saturday afternoons, my sister and I were dressed in beautiful “can-can” party dresses and shiny patent leather shoes. The parties were always adult centered, even if it was a child’s birthday, baptism, first communion or graduation.

My father would jokingly say, “We even celebrated the baptism of a doll.”

The kids were usually sent to play in the bedrooms. The coats were piled high on the beds creating a distinct mixture of Chanel #5 and Varon Dandy aftershave floating in the air. It was a wonderful delight as a child to fall asleep under all those coats. I remember feeling so warm and protected brushing against the fake furs.

I can still hear the slow-moving bolero, “Bésame Mucho”, and laughter from what seemed far, far away.

Television family nights were very predictable. On Saturday nights, my parents, abuela, Titi Anita and Tío Hernández would rush through dinner in order to watch The Lawrence Welk Show. I relished being bilingual and bicultural and I was so proud of the fact that my family felt the same way.

In a way, it was like living in two worlds. The elders also enjoyed The Ed Sullivan Showand The Wonderful World of Disney on Sundays. We spoke only Spanish at home but learning English was paramount. The music we listened to on the radio and record player was in Spanish.

My teenaged brothers preferred Frank Sinatra and American Bandstand but they also listened to one of the most popular music of the fifties; the mambo. I first heard Tito Puente, Tito Rodríguez and Machito—the Big Three from the Palladium Ballroom in that Kelly Street living room.

Although the media image of the South Bronx has been portrayed as a dangerous and impoverished, I remember it as a safe and nurturing environment. Our family life was simple and very enjoyable.

The 1950s was a very innocent and family-oriented decade for many of us. Before falling asleep, the last sound I heard was the familiar roar of the train. I could count on its scheduled arrival and departure. It never changed, just like my memories of Kelly Street.

2 thoughts on “Reality vs. Reputation: A Peoples’ Memoir of the Bronx”

Great story. I grew up in the Bronx, New York. Have many great memories of going to school, getting married and having my children in the Bronx. i live in Harlem now but my heart will always belong to the Bronx,

Pingback: Reality vs. Reputation: A Peoples’ Memoir of the Bronx | Marguerite Ward