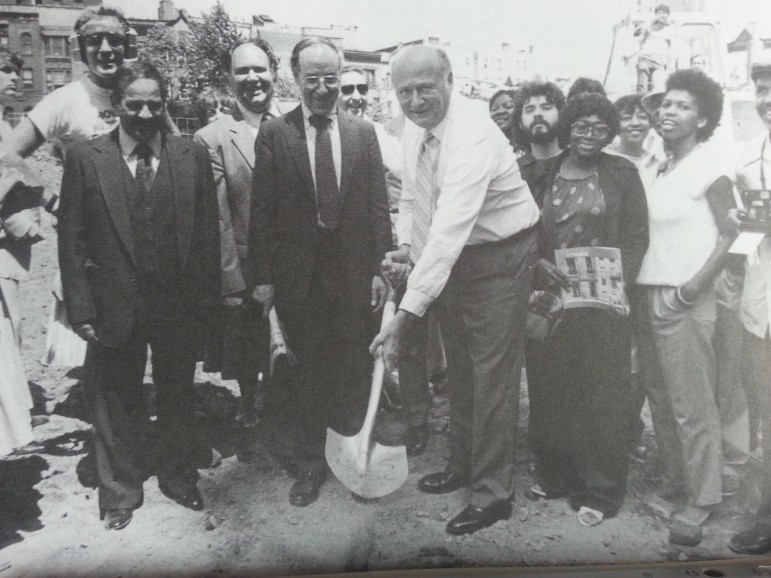

City Limits archives

During the Koch era, residents of supportive housing were generally required to prove sobriety before they got a room. Over the years, that thinking has changed.

***

New York City’s homeless population is no monolith, and the 2005 NY/NYIII supportive-housing funding agreement explicitly recognized that. Kingsbridge Terrace, a supportive housing facility run by Jericho Project in the Bronx, was in part funded for “Population F”—substance users who recently finished treatment.

Including substance users in supportive housing was controversial to earlier planners. While those agreements ended up including many homeless individuals who had struggled with addiction, they were accepted into the program because of serious mental illnesses, not because of their drug or alcohol problems. As Ted Houghton put it in his history of the field, “in our society’s constantly shifting definitions of deserving and undeserving poor, substance abusers rarely escape the latter category.”

Tori Lyon, the executive director of Jericho Project, says that allowing in active substance users was the most profound shift she saw in her 20 years at Jericho. At the start, she said, “we required six months sober. You were expected to remain sober.” As political scientist Thomas J. Main writes, in its first versions, New York’s supportive housing demanded that “homeless people sober up, take their medications, and demonstrate that they were ‘housing ready’ before they would be moved into an apartment.”

The city and state’s move away from requiring sobriety for housing showed the influence of the Housing First approach. In the ’80s and ’90s, homeless services in New York were a kind of ladder, with the street at the bottom and housing at the top. For the homeless woman addicted to heroin, or the man with severe schizophrenia, the way to climb was by demonstrating “good” behavior—by taking your medication, gaining “insight” into your mental illness, and most importantly, remaining sober.

Sam Tsemberis, a clinical psychologist hired to lead a street outreach program under Mayor Koch, began questioning this approach after hearing from street residents that what they wanted most was not treatment, social services or even shelter—but housing. With a state grant, Tsemberis started Pathways to Housing, which provided supportive housing without requiring sobriety or treatment compliance. The idea, Tsemberis wrote in a later study, was to turn the traditional ladder upside down. In some ways, this built on some supportive housing models from the 80s, like the “Heights,” a former SRO in upper Manhattan that made it voluntary for residents to use services like substance-abuse counseling.

The success of this approach and other experiments like it quickly became clear. A 2000 study compared Pathways to Housing to 65 “treatment first” providers in NY/NY I. The difference was striking: After 5 years, 88 percent of those in the Pathways program remained housed while only 47 percent using “treatment first” did. In the early 2000s, the approach spread across the U.S. A 2011 study reviewed the evidence for these initiatives nationwide and found similar levels of success.

Housing First has become, in some senses, policy in New York. In 2006, Mayor Bloomberg’s administration streamlined street outreach, making one provider responsible for each borough and encouraging Housing First principles. This countered the recommendations that an influential commission, led by a younger Andrew Cuomo, made to Mayor Dinkins in the early ‘90s: As the New York Times put it at the time, “The commission…would offer the homeless a richer array of services, including drug treatment, psychotherapy and job training, in smaller settings. But it would also require the homeless to take steps like enrolling in a drug-treatment program to qualify for subsidized permanent housing and it would strengthen enforcement of eligibility requirements for getting shelter, commission members said.”

Today, the ideals of choice and autonomy emphasized at providers like Jericho are informed by this tradition. Housing cannot be tied to sobriety or services, although most contracts require a set number of encounters between caseworkers and tenants each month.

Advocates underline that the voluntary nature of services does not mean abandoning those struggling with mental illness or addiction. Increasingly, providers are encouraged to use “evidence-based practices”; the city’s new proposal emphasizes “person-centered planning with a quarterly service plan; motivational interviewing; health and wellness services; recovery-oriented and trauma informed case management; harm reduction services; a progressive demand approach that encourages tenants to participate in services.”

But at the ground level, supportive-housing staff have learned they must creatively market these offerings. Sarah A. Harris, a senior social worker at Jericho Project, says residents who have cycled through rehab facilities, hospitals and other rigid institutions are often fed up with clinical lingo. At Jericho Project, staff members try to reframe their offerings to emphasize the choice involved. One relapse-prevention group had low turnout until it was renamed “Keeping the Balance.” They saw a total turn-around, Harris says.

Despite these changes in the model, many of the basic realities of transitioning from the street to permanent housing are and probably will continue to remain constant. For some residents, the simple act of sleeping in their own apartment for the first time in years takes some adjustment. Harris remembers a resident who couldn’t sleep because he kept waking up terrified after thinking he heard someone trying to break into his new apartment. “It was the refrigerator.” Harris says. After years on the streets and in shelters, it took time before he could put two and two together. Some of the men Harris works with have had extensive combat histories, but “homelessness itself is traumatic” she says.