Environmentalists say an Army Corps of Engineers’ plan to protect the city from coastal storms using walls and gates fails to address other climate change-related threats, like heavy rainfall.

Eleven years after hurricane Sandy killed 43 New Yorkers and caused $19 billion in damages, plans to barricade the city from coastal storms—with over 82 miles of flood protection measures—have yet to leave the drawing board.

The $52.6 billion dollar storm surge protection project will be funded by both the state and federal government and designed by the Army Corps of Engineers. Construction is set to take off in 2030 and take approximately 14 years to complete.

Last September, the Army Corps published a study that laid out the master plan and gave the public six months to weigh in on the draft. A decision on whether they will move forward with the proposal or start from scratch was due in July, but the Army Corps announced last month that it would be “delayed until later this fall,” with no specific deadline.

Meanwhile, 30 environmental groups are demanding a redo of the current plan. The main issue, according to advocates, is that it falls short of addressing climate change-related threats beyond coastal flooding, like heavy rainfall and sea level rise. They also want the project to incorporate more nature-based solutions like rain gardens and storage tanks to collect rainwater and tackle inland flooding.

“Our biggest concern is that this project is not a multiple climate hazard project. It is not accounting for sea level rise or any of the flooding brought on by the heavy rains that we have seen recently,” said Tyler Taba, senior manager for climate policy at the Waterfront Alliance, one of the environmental groups pushing back.

RELATED READING: ‘Predictable Emergencies’: NYC Flash Floods Spur Renewed Calls for Basement Legalization

Last month, a storm dumped more than seven inches of rain on New York City in less than 24 hours, flooding streets and halting public transit. Two years earlier, rains from Hurricane Ida caused similar inland flooding that killed 13 residents.

With the city facing multiple severe weather threats beyond the coast, advocates urge that the Army Corps project take other flood-risk precautions into account.

“The [current] project is addressing how to protect us from another Hurricane Sandy. And I totally understand that and we should absolutely be looking at storm surge as a legitimate risk in the region,” Taba added. “But should we be looking at it as the only risk on a mega project like this?”

Bryce Wisemiller, the Army Corps of Engineers’ project manager for the New York study—which focused on the five boroughs as well as neighboring New Jersey—said in an email that storm surge “is not the only flood risk under evaluation in this study” but adds that working them all into one project “may not be the most efficient and effective approach.”

“For this study area, by far, the most significant risk to life safety and property damage, as illustrated by Superstorm Sandy, is coastal storm surge,” Wisemiller said.

A plan with pitfalls

Over the last decade, the Army Corps of Engineers studied five possible solutions for barricading the city from coastal super storms like Sandy, and eventually wound up choosing one.

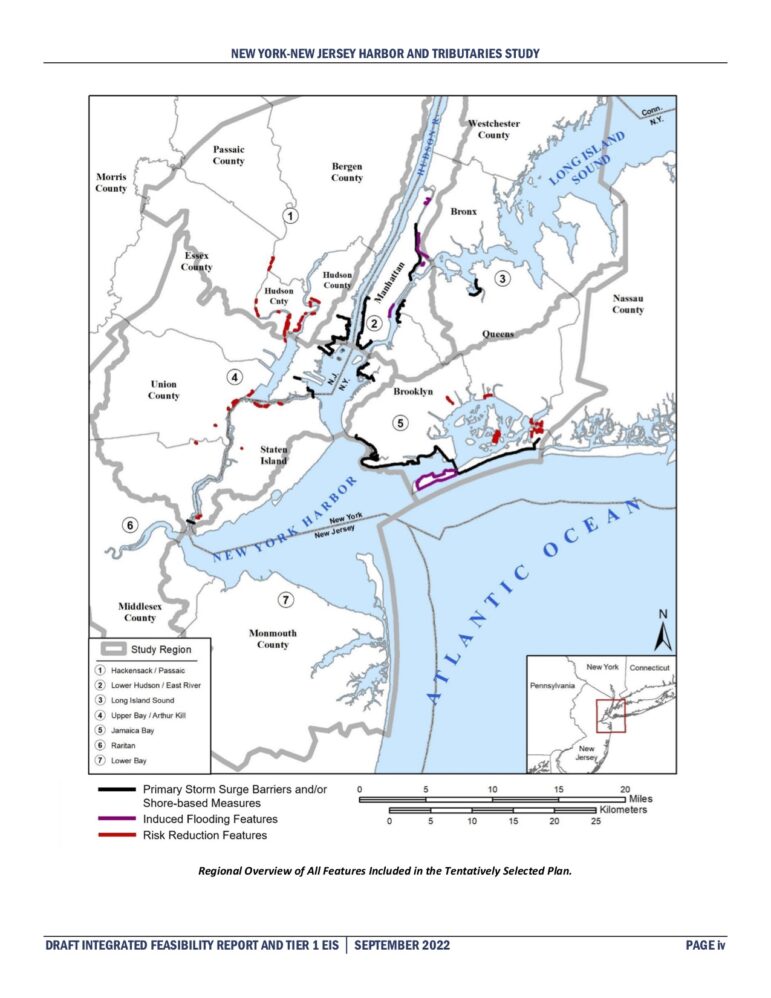

The selected plan, known as “Alternative 3B,” features 80 miles of on-land infrastructure like floodwalls, levees, deployable gates and elevated promenades. It also includes 2.2 miles of a variety of storm surge gates and other structures inside the water, including sea walls at 12 locations throughout the city.

New York-New Jersey Harbor and Tributaries coastal storm risk management feasibility study

A map showing where storm-surge barriers and other protections would be placed under the Army Corps’ draft proposal.For Kate Boicourt, director of NY-NJ climate resilient coasts and watersheds at the Environmental Defense Fund, however, the sea walls can present challenges.

“In some cases [the seawalls] can be problematic with heavy rains, because they can back up and create a bathtub effect,” Boicourt said. “Imagine you’re in a bathtub, and you slosh the water and it hits one side [of the tub] and it comes back at you. That’s what’s happening.”

And the bathtub effect can be particularly yucky when the sewers in New York City overflow during heavy rains. More than half of the city’s sewers use an archaic system that collects both sewer water and storm runoff in the same pipes. When it rains too much, the pipes can’t handle the amount of water coming in, causing them to spill over and dump untreated waste in a process known as Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO).

“Inland flooding is as large a concern as coastal flooding in a neighborhood like Gowanus,” said Andrea Parker, executive director at Gowanus Canal Conservancy.

Parker says one way to address the issue is to invest in a flood risk plan that can help build a more “spongy city” as she calls it. In other words, create mechanisms to absorb or collect the rain before it ever makes its way into the city’s pipes.

“I’m talking about green infrastructure like rain gardens that hold water or storage tanks and rainwater systems where water gets reused within the building. There are a ton of different technologies that can be implemented to basically slow the way that stormwater is getting to the sewer,” Parker said.

Wisemiller, from the Army Corps of Engineers, said in an email that the focus of the storm surge project has been on measures “that can best possibly manage severe storm risks” and added that because “green and nature based solutions typically can best manage more frequent, less severe storm impacts, their incorporation into the plan, so far, has been limited.”

But last month, when New York was grappling with remnants of inland Tropical Storm Ophelia, the city witnessed one of its wettest days on record—canceling flights, closing down subway lines and flooding neighborhoods.

“We haven’t yet really internalized increased precipitation as the really, really dangerous piece of climate change. But it is,” Parker told City Limits.

Councilmember Lincoln Restler, who publicly voiced his concern about the draft plan at a hearing earlier this month, echoed the sentiment.

“I think the scale of the devastation of Superstorm Sandy has oriented policymakers in the ensuing years toward high expensive coastal resiliency projects to try to keep our waterfront community safe. And they’re necessary and important. But they’re not the whole enchilada,” he added.

The Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice (MOCEJ) told City Limits that when it comes to mitigating flood risks, the city needs to be prepared for multiple weather threats.

“Our infrastructure should protect us from multiple climate hazards while supporting community uses all New Yorkers can benefit from,” said Executive Director, Elijah Hutchinson, in an email.

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Mariana@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org