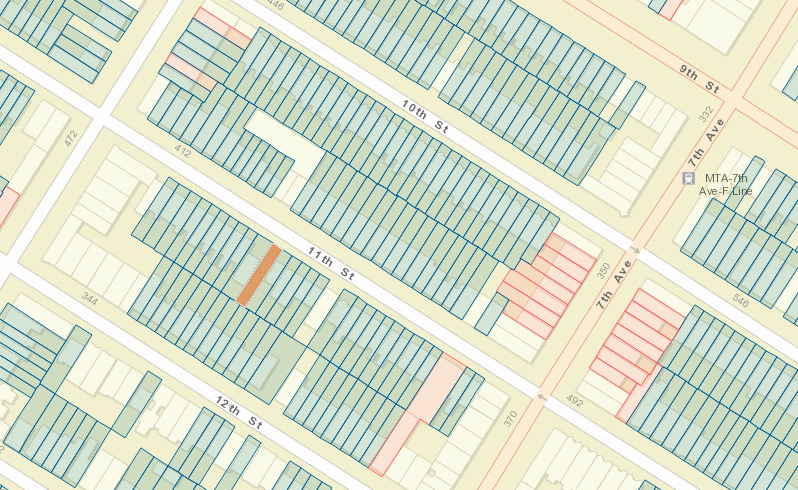

The city's tax map for Park Slope.

When you’re a straight, White, upper-middle-class, non-disabled, gentile natural-born citizen like your correspondent is, it’s rare to feel like you are getting screwed. So it was strange this week to learn this fact: Mayor de Blasio’s family home is worth more than four times what my house is but I’ll pay 17 percent more this year in property tax than he does.

I realized this after reading Sally Goldenberg’s Politico story on Monday about the mayor’s search for a new tenant for a second property he owns. Her article noted the property tax charges the mayor takes both on that house and his pre-Gracie Mansion residence. The tax bill on the mayor’s primary residence sounded a little low compared with the amount that gets rolled into my own mortgage payment.

And it is. My home in the Norwood section of the Bronx has an estimated market value of $400,000 and my property-tax bill this year is $4,186. De Blasio’s place in Park Slope has an estimated value of $1,688,000 and the mayor is paying $3,581.

So, yeah, that’s a little messed up.

This is not de Blasio’s fault. Rather, it is one of many quirks and inequities in a system that the city’s political class has shown little interest in fixing because of the dangerous politics around resetting who wins or loses from it.

I’m not saying my taxes are too high, mind you. Truth be told, I’ve always thought I was getting a pretty good deal on taxes—city, state and federal. I’m pretty lucky to own a house in a city where tens of thousands of people are in public shelters. I am not expecting the Times’ Neediest Cases series to call looking to do a profile.

Still, there does seem to be an equity issue here. Why does a system where charges are based on property values charge more to someone whose property is valued less?

The reason, according to city Department of Finance Deputy Commissioner for Property Timothy Sheares, dates back to when the current property tax system was created in the early 1980s.

My house and de Blasio’s are in the same tax class (Class 1) and pay the same tax rate (19.9910 percent). That tax is applied not to the estimated market value of the property but to a fraction of it called the “assessed value” which is supposed to be 6 percent of the estimated market value.

But neither the mayor nor I are assessed at that level. The assessed value on my lair is 5.2 percent of the estimated market value. The mayor’s assessment is 1 percent of his market value. That’s because we’ve each benefited from a cap the property tax law placed on how much an assessment could rise year to year. De Blasio just benefits from this more because his property has gained a heck of a lot more value in recent years. Basically, Park Slope has had a better 21st Century than Norwood, at least in terms of property values.

The logic behind the cap is clear. Just because you live in a neighborhood that suddenly gets hot, boosting the worth of your home, doesn’t mean you have a greater ability to pay. Unless you sell your house or take out a second mortgage or something, you don’t benefit in a tangible way from the increase in the value of your home. The system doesn’t want to punish people simply because the city changes around them.

At the same time, the cap means the city is profiting relatively modestly from the increase in the value of the property within its borders. And it also introduces inequities between property owners, and weirdness like your tax bill going up even if the property value goes down because the assessed value is still trying to catch up to earlier increases in its worth. This is hardly the only quirk in the city’s property-tax system, as our Ruth Ford made wonderfully clear in a 2015 article.

In 2014, it looked as it the city might take on the task of fixing the system: City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito established a commission to study possible changes. But the effort fizzled. The commission tuned its attention instead to reviewing the tax incentives the city uses to encourage economic development—a worthy topic itself, and less of a minefield than property taxes. The caps on changes in assessed value, which create disparities in trying to avoid other forms of unfairness, are just one example of the cross-wiring and complexity that characterize the system. There is no way to fix it without making some people pay more than they are now, and that’s not usually seen as a way to win votes.

For its part, the de Blasio administration says any changes to the system need to be made in Albany, which sets the rules for it; the city just changes the tax rate. “This is a state law,” Sheares says. “The state would have to revisit this.”

Property taxes are a problem almost wherever you go. In municipalities that depend on them for revenue, they can get really high, and they often lead to huge disparities from town to town in the funding available for schools. While property taxes are a critical revenue source for New York, the city is fortunate to also have an income tax, which buffers the city a little from changes in different parts of the economy and limits the impact on residents of the flaws inherent in either system.

In fact, if you’re talking about a New Yorker’s overall tax burden, the progressive city income tax (where de Blasio pays much more than I do because he makes much more) probably offsets some of the quirks in the property tax system—although the Fiscal Policy Institute has estimated that because of the property tax the city’s overall tax structure is regressive, meaning the rich pay proportionately less than people with lower incomes.

Give the property tax a little credit: It’s an attempt to tax wealth, something U.S. governments don’t otherwise do—preferring to tax the transfer of wealth between parties and the transformation of assets into income—even though there are good arguments for it. It’s just a rather clumsy attempt to do so.

An election year seems an unlikely time for revived talk about property-tax reform. So for now at least, I’ll fork over my fee and cheer myself up with this realization: Park Slope might have the cute restaurants and leafy sidestreets, but Norwood is still where it’s at when it comes to … assessed value.

Awwwwww yeah!

Assessed Value on the Two Finest Homes in New York City

1981-2017

3 thoughts on “UrbanNerd: Why I Pay More than the Mayor in Property Taxes and how it Makes me Feel About Myself”

I own a Class-1 1-family home on SI and will pay $5300/year in NYCRE taxes.

I live in a Sunset Park brownstone with $5K in property taxes. My Irish relations refer to it as Murphy’s Hotel.

The prices for these edifices of late are out-of-control. Please explain.

“DeBlasio doesn’t pay much in income taxes either. He paid absolutely no taxes on his rental incomes from his two houses. ” paid $37,757 in federal taxes — about 17 percent of his total income.

But the mayor and his wife also avoided paying thousands of dollars by making a byzantine tax code work for them. In addition to his reported income, virtually all of it from his salary, the mayor reaped $106,000 from rents at two houses his family owns in Brooklyn.

But de Blasio and McCray didn’t pay taxes on any of this cash. Why?

A big reason is the mortgage-interest deduction, worth $61,219. Contrary to the de Blasios’ prim statement about being grateful to have a “home,” the mayor and his wife don’t have a Brooklyn home at the moment, but run an apartment-rental business while they live in Gracie Mansion. That’s admirably entrepreneurial, and paying the interest on business debt is a real cash expense.

But the mayor also avoids taxes by constructing a paper loss. The de Blasios took a $26,970 “expense” for “depreciation” of their houses. That, plus much smaller expenses, left the first couple with a $6,247 loss on renting out the apartments, meaning they don’t have to pay taxes.”http://nypost.com/2017/04/20/how-landlord-de-blasio-games-the-tax-code/