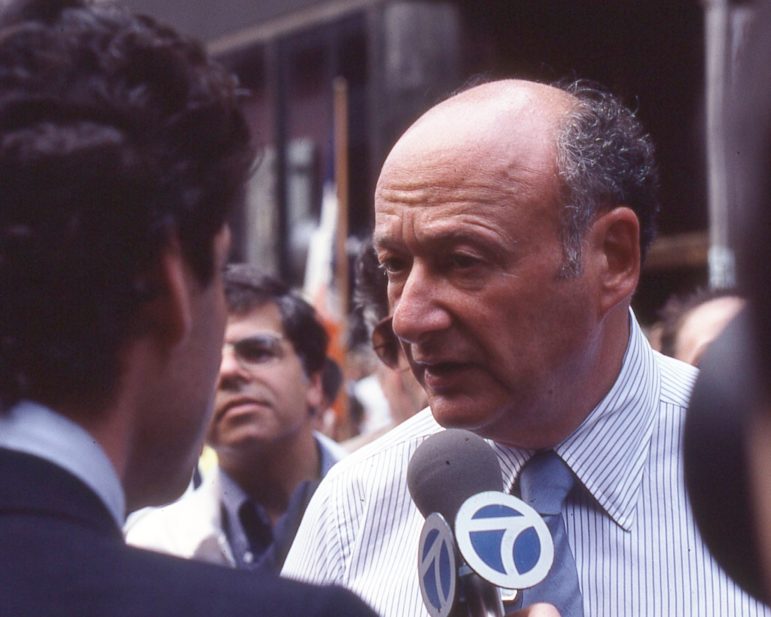

Bill Golladay

The tragic deaths of homeless children at a hotel convinced Mayor Koch to try a different approach. It's time, the author argues below, to try it again.

In the early 1980s, I was First Deputy Commissioner of NYC’s Adult Services Agency in the Human Resources Administration, the forerunner to today’s Department of Homeless Services. Then, much like today, the city was in the midst of a homeless family crisis. Emergency shelters were overwhelmed, and the city began placing homeless families into private hotels, many of which became notorious like the Martinique and Holland.

These facilities were no place for families with children, homeless or otherwise. Their owners reaped millions from city coffers, while families lived—and sometimes died—in squalor. But it wasn’t until three young homeless children burned to death in their room at the Brooklyn Arms Hotel that we in the Koch Administration realized that housing families in hotels had to stop.

In response, we put together a capital construction program to develop what we called Tier II Transitional Housing: government-regulated facilities with clean, safe, private rooms and services where homeless families would be helped to transition back to permanent housing. They were operated by experienced non-profit providers, and they worked. In time, the use of for-profit hotels declined and the homeless crisis began showing signs of manageability.

I could never have imagined that almost 40 years later the city would be facing another unprecedented homeless family crisis, and worse, that it would be beholden as never before to for-profit hotels and landlords. More than half of all homeless families today are sheltered in these unregulated accommodations at a cost to the taxpayer of roughly $250 million dollars a year. And the recent death of two children in one of these facilities, like with Koch, is the de Blasio Administration’s wake up call to stop depending so heavily on their use.

The city argues that it needs such facilities because communities object to opening new shelters in their neighborhoods. The fact is that communities are hostile because shelters have been forced on their neighborhoods with little, if any, community planning or participation.

But there is a better way to move forward and serve homeless families while also meeting the needs of the communities from which they come. The original Koch plan was to convert transitional housing facilities over to community use when the homeless crisis ended. Although that never happened, the idea was a good one; De Blasio would be wise to pick up where Koch left off.

Imagine a scenario where the elements of a neighborhood community center would be integrated with Tier II transitional housing to produce a new Tier III Community Residential Resource Center (CRRC), a residential facility with the core mission to provide at a minimum comprehensive job readiness and employment services, adult and youth education programs, child care and health care services to meet the needs not only of the facility’s residents, but of the community-at-large. CRRCs could be the source of pride rather than scorn given that they would contribute to—rather than take from—communities.

CRRCs could be readily constructed on the abundance of NYCHA’s public housing grounds currently being leased to private developers. Why not put these public lands to public use and begin to reduce the city’s dependency on for-profit hotels?

Over the last 30 years, there has been very little change in policies to address family homelessness. But a capital investment to develop new Tier III facilities would positively transform the entire family shelter system. The homeless and the community would be equally served while the costs of doing so would go down. It is an old idea whose time has come, and a win-win policy for all.

When I was first deputy commissioner, there was a young Legal Aid attorney, Steven Banks, who relentlessly pursued a campaign against the city in the courts to insure that homeless children and their families were afforded clean, safe placements while in shelter. Today, a more seasoned Banks is the Commissioner who oversees the city’s homeless and social services and finds himself in a position where he has little choice but to place families in the very hotels that he once reviled. Knowing firsthand the benefits and risks to government and the goals of advocates, Banks has the knowledge of what must be done and the power to get it done. Why not use it?

One thought on “CityViews: Homelessness Crisis Demands a New Kind of Shelter—Not More Hotel Rooms”

Whatever the percentage of homeless to those in homes are, in times like these we should be doing more to decrease this population and lay a groundwork for domicile/residential security!!!