Murphy

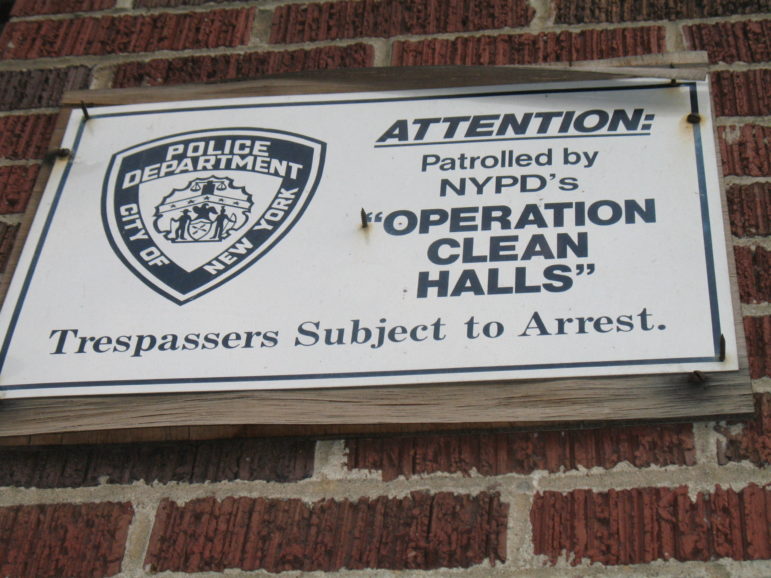

Law-enforcement initiatives like Clean Halls contributed to disproportionate policing—the arrest and prosecution of low-income people of color for offenses that are common everywhere.

A cascade of crises is forcing America to confront the racism of its past and present—from overt acts of hate to subtler injustices that shape our society. Over 16 weeks, City Limits and Enterprise Community Partners will feature prominent New Yorkers’ views on how race and housing policy intersect to create a legacy each of us must confront, and the way forward we should take together. These are not necessarily views we endorse. But they are views we fully believe are important to share with each other. Here is the 10th post in our series. Read the rest here.

* * *

An hour ride on most NYC subway lines should be enough to see how New York City, for all its diversity, is an economically and racially segregated city. A few stops along that same ride can also illustrate how policing in communities varies depending on the neighborhood. Take the D train from 59th-Columbus Circle to The Bronx Defenders’ office in the South Bronx and this will be evident. The correlation is no coincidence. Over-policing and housing segregation are two sides of the same coin—the two systems are embedded in each other, making it impossible to dismantle one without fundamentally changing the other.

Previous articles in this City Limits series have explained how New York City became so persistently racially segregated and the impact such segregation has on people’s access to educational, employment and economic opportunities in the long-term. Residential segregation, whether imposed by law or as the result of decades of racist housing policy and real estate practices, as well as other economic forces, has created and concentrated disadvantaged neighborhoods of color, specifically with Black and Latino majorities, with higher rates of poverty compounded by decades of government divestment and, in turn, higher crime rates. Such segregation serves as a system of social control. The police abuses that have become the focus of a national conversation about race in the United States take place in that context.

As the Director of the Civil Action Practice at The Bronx Defenders, a community-based holistic public defender office in the South Bronx—one of the most under-resourced, segregated, and over-policed districts in the city—I see every day how people in this vibrant community struggle to escape a cycle of poverty and criminalization that is often passed from generation to generation and is sustained by the manner in which segregated, unstable and poor quality housing—whether private or public—is used as a vehicle for increased policing and surveillance of an entire segment of the population.

Take, for instance, the stop-and-frisk practices that were deemed unconstitutional in 2013 after having been used for decades to target those neighborhoods with the highest concentration of communities of color; or programs like Operation Clean Halls, a type of stop-and-frisk in private housing that as far back as the early 90’s enabled police officers to patrol the hallways of privately-owned buildings in “high-crime” areas. In some Bronx neighborhoods, nearly every private apartment building was enrolled in the program and police officers would conduct regular floor-by-floor sweeps, stopping and questioning almost everyone they encountered and exposing tenants and guests of these buildings to a heightened risk of unlawful NYPD stops and arrests. Add to this mix the policing of so-called “quality of life” offenses, also known as broken windows policing, which allowed police to profile and criminalize harmless, non-violent acts, such as riding a bicycle on the sidewalk, spitting on the ground, playing loud music, jaywalking and littering, to name a few—acts that take place everywhere in New York but are only policed in some neighborhoods. Additionally, the aggressive enforcement of the War on Drugs, dating back to the 80’s, led to the disparities in arrests, prosecutions, convictions and incarceration due to purported drug sales and possession in communities of color, despite the fact that blacks and whites used and sold drugs at roughly equal rates. Such practices are just a few examples of the different police programs that allowed for the constant surveillance and policing of communities of color under the banner of “law and order.”

Constant police presence in segregated spaces of low-income communities of color like the South Bronx only increased the probability of arrest and further involvement in the criminal justice system. An arrest can trigger a host of grave additional civil consequences, such as losing your job, housing, other social and civil rights—in addition to the stigma of being labeled a “criminal.” Nowhere is this more true than in the housing context where an arrest, even before a conviction, can result in an eviction proceeding. These civil consequences fuel the cycle that marginalizes low-income people of color, keeping communities of people under increased government control and resulting in systemic deprivation of opportunity in all aspects of life, thus reinforcing segregation into under-resourced neighborhoods and further destabilization of families.

Take the case of Carl, a young man from the South Bronx whom I represented a few years ago. Carl has lived in the south Bronx his whole life. Carl was raised by his grandmother in her rent-stabilized apartment, which he “succeeded” to when she passed away; he was able to get assistance through Section 8 to make his apartment affordable. Carl was slated to start working as a locksmith. He is a single dad with a young son. Carl is also Black. One day Carl was across the street from his home when officers stopped him. They told him they believed he had marijuana on him and that further, he tried to sell it to someone on the street. They handcuffed Carl and asked him where he lived and when he pointed to the building across the street, they took him to his apartment, took his keys out of his pocket, went into his apartment and searched it. They found some pot and took Carl to the precinct, after which time he was booked, charged and prosecuted for possession of marijuana. He also was investigated by the Administration of Children’s Services because his son was home when the police searched the apartment and he was arrested.

Carl told me he was used to being stopped and harassed by the police and that he experienced it before—sometimes leading to an arrest, sometimes not. What did come as a surprise to Carl was that several months after his arrest, he received a notice from the building’s landlord stating that they would seek his eviction on the basis of selling drugs out of his apartment. Shortly after that notice, he received another letter stating that the city would seek to terminate his Section 8 housing assistance. He received these notices while he was innocent, not proven guilty, and was still going back to criminal court, waiting for a trial. Carl had a public defender in criminal court, but since no right to counsel exists in the housing context, he was expected to fend for himself to prevent his own eviction and to keep his Section 8 subsidy because he could not afford a private housing lawyer. Because of these cases, Carl was also unable to work as a locksmith, leading to further income instability.

Carl’s story is not the exception. He lives in a heavily-policed neighborhood with an expectation that, based on where he lives and what he looks like, he will have police encounters often and may even be arrested from time to time. This is his accepted reality. Our office represented Carl in all of his cases, and eventually, all three cases were dismissed.

The City of New York has invested millions of dollars in building affordable housing and in increasing legal services for tenants who are facing eviction and displacement. There have also been a slew of policing and criminal justice reforms in recent years, focusing on racial and economic disparities in policing, the unconstitutional and unjust nature of policing programs like stop-and-frisk and broken windows, and from the realization that years of arresting and incarcerating Black and Brown people for non-violent drug charges is not an effective approach to crime fighting and is fundamentally unfair and cruel.

But we must step back and take a more integrated approach to addressing these problems because one affects the other and we cannot take a siloed approach to achieve real change for those communities most impacted. Social and economic investment in communities that have been historically neglected, like the South Bronx, is critical. We must have a right to counsel in any civil proceeding that arises as a consequence of a criminal charge, first and foremost in housing court. We must rethink and revise the multitude of civil punishments designed to further penalize people in addition to criminalizing them, given the disparities in the policing of low level and non-violent, sometimes even harmless, acts.

When thinking about the racially and economically segregated nature of New York City’s neighborhoods, it is important to consider the structural role it plays in the policing of communities of color. In order to increase equity in our city it is essential that we take an integrated and holistic view to bridge the gap between housing and criminal justice reforms and to create meaningful change for the communities that need it most.

Runa Rajagopal is the director of the civil action practice at The Bronx Defenders.

One thought on “Building Justice: How Segregation Enables Over-Policing of Communities of Color”

I think most NYCHA tenants are happy with the NYPD patrols. What’s so wrong with keeping out trespassers? If someone was trespassing on my property I’d have to assume their intent was criminal.