Colin Lenton

2010: A house in southeast Queens, an area hard-hit by the foreclosure crisis.

A cascade of crises is forcing America to confront the racism of its past and present—from overt acts of hate to subtler injustices that shape our society. Over 16 weeks, City Limits and Enterprise Community Partners will feature prominent New Yorkers’ views on how race and housing policy intersect to create a legacy each of us must confront, and the way forward we should take together. These are not necessarily views we endorse. But they are views we fully believe are important to share with each other. Here is the ninth post in our series. Read the rest here.

* * *

This summer, a federal jury in Brooklyn did something unprecedented: following a lengthy trial, it ruled that Emigrant Savings Bank had discriminated against eight New York City homeowners of color in a first-of-its-kind “reverse redlining” verdict. The jury agreed with the plaintiffs and their attorneys at Brooklyn Legal Services that Emigrant Savings Bank aggressively targeted Black and Latino homeowners with poor credit and high equity in their homes for subprime mortgages with predatory terms, and in doing so, violated the Fair Housing Act, Equal Credit Opportunity Act and New York City Human Rights law.

But Emigrant was far from alone in targeting communities of color for toxic lending products in the years before the 2008 housing market collapse: rather it was part of a wave of predatory subprime mortgage lending that crashed the housing market and drove the U.S. into a devastating economic recession. While the foreclosure crisis has largely receded from today’s headlines, its impacts continue to reverberate for many families and their communities throughout New York City and nationwide. For Black and Latino families, the crisis exacerbated an already existing racial wealth gap, adding yet another chapter to our shameful history of housing discrimination.

High cost loans for people of color

The Emigrant trial centered on its STAR NINA mortgage program, which did not require proof of income or any assessment that the borrower was able to repay: rather it used the equity homeowners had built in their homes as its guarantee. STAR NINA also had a built-in interest rate hike to 18 percent if a borrower missed even one payment, a highly punitive measure that would be extremely difficult to pay.

According to Brooklyn Legal Services, Emigrant aggressively targeted communities of color with its STAR NINA advertising, spending the vast majority of its marketing dollars on newspapers with an almost exclusively Black or Latino readership: Black Star, Caribbean Life, Hoy, and Mizona Hispana. Unsurprisingly, the mortgage product was disproportionately used by people of color: Even when accounting for factors like income and credit score, STAR NINA loans were 32 percent more likely to be found in majority Black neighborhoods than White ones.

The racial targeting for toxic, subprime mortgages seen in the Emigrant case was commonplace in the years preceding the foreclosure crisis. In 2012 Well Fargo agreed to pay the federal government $175 million after an investigation found 34,000 instances where Wells had charged Blacks and Latinos higher fees and rates on mortgages than it would for White borrowers with similar credit. One Wells Fargo subprime loan officer described how Wells targeted communities of color in Baltimore for subprime loans: “We just went right after them… Wells Fargo mortgage had an emerging-markets unit that specifically targeted black churches, because it figured church leaders had a lot of influence and could convince congregants to take out subprime loans.” Another Wells loan officer reported that his coworkers referred to subprime loans as “ghetto loans,” and minority customers as “mud people.” Meanwhile, in New York City, a New York Times analysis found that Black families earning more than $68,000 a year were nearly five times as likely to hold subprime mortgages than Whites of similar or even lower incomes.

The crisis and the wealth gap

Just as homeowners of color were targeted for unsustainable subprime loans, they have borne the largest brunt of the foreclosure crisis. Although the majority of homeowners affected by the foreclosure crisis were White, homeowners of color were twice as likely to lose their homes as a result of the crisis. Because the majority of Black and Latino family wealth is tied to the home that they own, they were doubly hit by the foreclosure crisis: They were at greater risk of foreclosure due to predatory lending and other factors, and their wealth disproportionately suffered from the steep drop in property values that followed the crisis. Half of the collective wealth of Black families was lost during the Great Recession, while Latino families lost 67 percent.

While the racial wealth gap has always existed in U.S. society as a pernicious legacy of our history of slavery and racial discrimination, it has gotten worse since the Great Recession. In 1984, White families had a median wealth 12 times that of Black families and 8 times that of Latino households. After the crash, it increased to 20 times that of Black families and 18 times that of Latino ones. Unfortunately, the racial wealth gap in this country is not only appallingly large, it is growing increasingly insurmountable: A recent report found that it would take Black families 228 years to amass the same amount of wealth White families have today, if average Black family wealth continues to grow at its current pace. For Latino families, it would take 84 years.

From redlining to reverse redlining

Reverse redlining and its devastating impact on Black and Latino wealth did not happen in a vacuum; rather, it exists within the context of historic discrimination in housing policy, which systematically deprived people of color from building wealth through affordable, conventional home purchase financing.

From the 1930s until the Civil Rights Act of 1968, the federal government led the charge in enforcing housing segregation and institutionalizing the racial wealth gap through redlining, a practice that denied mortgage credit to communities of color. Created in 1934, the Federal Housing Authority developed lending standards for mortgages, relying on maps made by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation. These maps drew red lines around non-White neighborhoods that rendered them ineligible for credit, meaning that people living in them were deprived of affordable 30-year mortgages as well as loans to make investments or needed repairs in their homes. They also promoted segregation in White neighborhoods by insisting that the properties whose mortgages they insured contain racially restrictive covenants, deed restrictions that would prevent non-White people from purchasing the property in the future.

In the absence of conventional lending, homeowners of color were forced to turn to unsavory lenders who engaged in “contracts for deed,” a risky, predatory form of home purchase financing in which the buyer receives a high-interest loan and agrees to make monthly payments to the lender for a certain number of years, in exchange for receiving the deed to the home upon completion of all payments. In the meantime, the buyer does not build any equity in the home, and if the buyer misses a payment or fails to adhere to some aspect of the contract, they are swiftly evicted, forfeiting their down payment as well as all other payments made. In “The Case for Reparations,” Ta-Nehisi Coates characterizes the contract-for-deed model as “a predatory agreement that combined all the responsibilities of homeownership with all the disadvantages of renting.” Coates describes how deed peddlers targeted Black homebuyers in Chicago, selling them homes in poor condition at inflated costs, and quickly moving to evict them. If the homeowner missed a payment or failed to make costly repairs on time. The seller would then keep their money, and quickly seek out another purchaser to repeat the scheme.

Race, wealth, and homeownership after the crash

Both redlining and reverse redlining negatively affected communities of color seeking to build wealth and own their homes. Redlining denied credit to minority homeowners, while reverse redlining targeted the same homeowners with predatory credit. Today, redlining is illegal and many of the most predatory loans that caused the foreclosure crisis are now no longer used. However, the legacy of both practices lives on in New York City’s neighborhoods today.

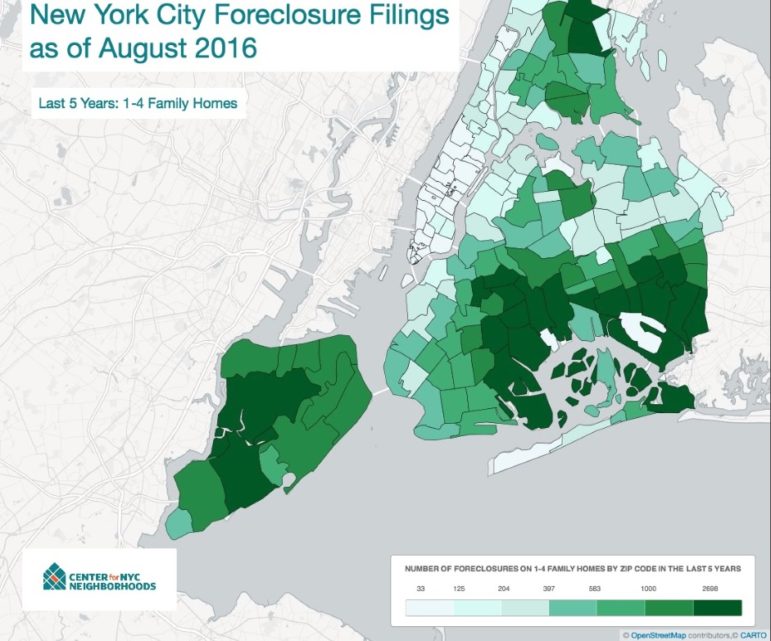

Perhaps the most obvious legacy of the crisis is seen in the thousands of New York families who are at risk of displacement due to foreclosure and financial instability. Today, tens of thousands of New York City homes are in the residential mortgage foreclosure process. The families who own those homes are mostly Black and Latino: Over 60 percent of the homeowners at risk of foreclosure we see at the Center are Black, and over 20 percent are Latino. Many live in the same communities that were redlined a couple of generations ago.

CNYCN

Another major financial pressure for homeowners in these neighborhoods is tax and water debt, which New York City sells to private investors in its annual lien sale. Once their liens are sold, homeowners will often watch their relatively small debts quickly balloon, with daily compounded interest rates and fees adding to their burden. According to our analysis of the 2016 lien sale, homeowners living in Black neighborhoods were six times more likely to have liens sold on their property, and those in Latino neighborhoods were twice as likely, than homeowners living in majority White neighborhoods.

Another persistent legacy is the wave of foreclosure rescue scams targeted at homeowners at risk of foreclosure. Almost immediately after the housing market collapsed, these scam operations sprang up targeting homeowners desperate for help, with many of the same actors who had marketed risky mortgage products re-establishing themselves as supposed foreclosure experts. These scammers took advantage of the general confusion and chaos caused by the foreclosure crisis and ripped off homeowners, charging them thousands of dollars for nonexistent services, preventing them from seeking legitimate help, and in the worst situations, costing them their home. Such was the case with Launch Development, whose principals were charged with conspiracy to commit wire fraud as part of a series of deed-theft scams targeted at New York City homeowners. Among other wrongs, the defendants allegedly misled homeowners into signing blank documents that they were told were mortgage modifications, when in fact, the documents were used to transfer the title to their homes. According to Brooklyn Legal Services, which is representing several homeowners suing Launch, the company is alleged to have almost exclusively targeted their activities to Black and Latino neighborhoods.

The good news is that free, high-quality help is available to New Yorkers impacted by the foreclosure crisis through New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman’s Homeowner Protection Program, which is funded through legal settlements with financial institutions for their role in creating the foreclosure crisis. Throughout New York State, homeowners can work with attorneys and housing counselors at community-based organizations to find solutions to their mortgage nightmares, such as mortgage modifications that will reduce their payments to affordable levels.

But there is much more to be done. We need to address and reform policies that disproportionately impact homeowners of color, such as the city’s tax lien sale, as well as the federal government’s Distressed Asset Stabilization Program, an FHA program that unloads nonperforming mortgages to private investors at steep discounts, and which, according to a recent lawsuit filed by MFY Legal Services, disproportionately harms homeowners in Black neighborhoods. We must also examine new models of asset building for low- and moderate-income communities and implement affordable homeownership models such as community land trusts, whose homeowners weathered the financial crisis with dramatically fewer foreclosures despite facing the same economic pressures. It is not enough to bemoan the past. Instead, we can and must take action to address the impacts of the foreclosure crisis and close the racial wealth gap today.

***

Caroline Nagy is the deputy director for policy and research at the Center for New York City Neighborhoods.

4 thoughts on “Building Justice: The Lasting Racial Stain of the Foreclosure Crisis”

Pingback: Community Developments: Racial Wealth Gap, Gautreaux Case and Fair Housing – Right Now Help Services

Pingback: "Stopping Foreclosure Rescue Scams in Their Track" and other headlines from 2016 - Center for New York City Neighborhoods

Pingback: Building Justice: The Lasting Racial Stain of the Foreclosure Crisis (City Limits) - Center for New York City Neighborhoods

Pingback: How a Public Bank Could Help You – The Nation. – Short Term Wealth