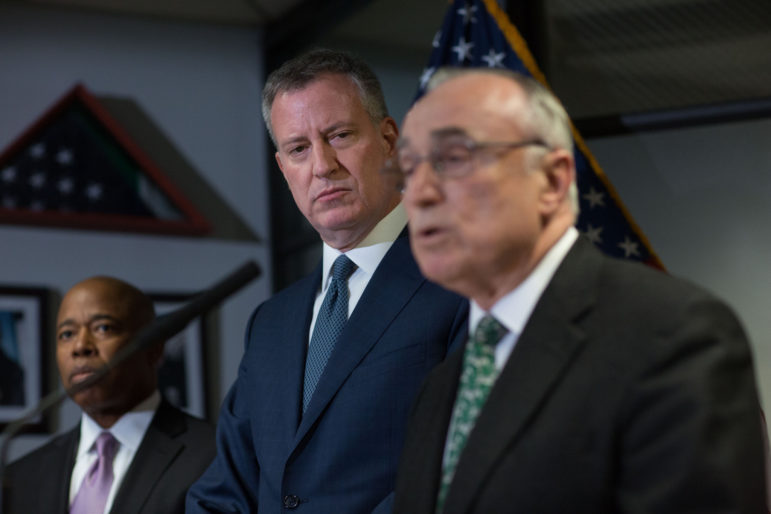

Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office

Bratton's stature was both an asset and a liability for the mayor.

Come September 1, nearly three years after Bill de Blasio won the Democratic primary thanks to a television commercial that critiqued the way New York was policed during the Bloomberg era, city residents will learn how the mayor wants it policed now.

With Bill Bratton gone, de Blasio will no longer be the second-biggest name at press conferences about crime statistics, new NYPD initiatives or alarming incidents of alleged police abuse. As impressive as incoming commissioner James O’Neill’s resume is, his name is not synonymous with an era in American policing. Nor will O’Neill be a police commissioner who by agreeing to come back to One Police Plaza in 2014 validated a mayor-elect’s ability not just to keep a lid on crime but also to manage the city despite limited executive experience.

With Bratton at his side, de Blasio reassured the business community and made it difficult—though not impossible—for his enemies on the right to deploy their ready-made narrative of a city sinking into violent chaos. It is widely assumed that Bratton also helped keep the PD’s rank and file from mutinying against the mayor in 2014 after his comments about the Eric Garner killing and after the slaying of two cops in Brooklyn.

The argument here isn’t that we know de Blasio let Bratton do whatever Bratton wanted. The point is precisely that we don’t know where the lines of authority were drawn.

De Blasio speaks very forcefully about his support for what he calls “quality of life” (a.k.a. “broken windows”) policing, Bratton’s brand, so it’s possible the mayor wouldn’t have done a thing differently if a celebrity commissioner weren’t in charge at One Police Plaza. But there was that little thing where the mayor refused to add more headcount to the NYPD, then caved when Bratton outmaneuvered him with the Council. And there were the times de Blasio and Bratton sent markedly different signals about the role of marijuana in violent crime and the morality of Black Lives Matter protesters. Maybe some of that daylight was visible only because we were all looking for it. But this much is certain: de Blasio was never in a position to exile Bratton the way Rudy Giuliani did two decades ago.

Given how much political weight rests on the crime numbers, the power dynamic between the mayor and the police commissioner is always going to be complicated: Each holds the other’s job security in his hands. If it turns out that de Blasio delegated rather generously to the sharp-featured Bostonian, he wasn’t the first mayor to let his police commissioner do most of the driving. Mayor Bloomberg, for one, seemed to give Ray Kelly plenty of room. It’s interesting to speculate whether the stop-and-frisk numbers would have reached such absurd heights if Bloomberg, who was no great civil libertarian but was pretty adept at reading a balance sheet, was more closely managing public safety.

When it comes to de Blasio’s ledger, the question is whether Bratton added more to his first 31 months than he took away. The numbers don’t lie: Crime is down and stop-and-frisk is all but gone. Those both reflect trends that were in place when de Blasio took office, but in their degree they rebut many a naysayer who predicted the rapid return of The Bad Old Days after de Blasio’s inauguration. Bratton’s presence didn’t stop cops from turning their backs on de Blasio at Woodhull Hospital; at Officer Liu’s funeral a few days later, cops ignored Bratton’s request that they show a little respect for the the mayor. Nor did Bratton prevent the NYPD work slowdown that occurred around the same time. He did help the mayor put a lid on the revolt, though the PBA is still in open warfare with de Blasio.

Basically, Bratton gave de Blasio credibility with the city’s political center. But the right was never going to give the mayor a chance no matter who he picked to run the cops. Meanwhile, for many in communities of color and on the left—de Blasio’s political base and the ticket to his survival in 2017—Bratton was more liability than asset, because a significant number of those New Yorkers feel “broken windows” is as much a problem as stop-and-frisk was.

It’s impossible to say what life would have been like had Bratton not returned to One Police Plaza. The more practical question for cops and the residents they police is whether anything changes now. O’Neill, the third consecutive Irish-American NYPD commissioner (and they say our time in the sun has passed!), emphasized continuity at yesterday’s press conference.

But both he and the mayor stressed the potential of Neighborhood Policing to fundamentally alter how law enforcement works in New York. Said de Blasio: “As the architect of neighborhood policing, he’s creating a model that I believe we’re going to make work here. I believe it’s going to change this city.”

O’Neill also addressed the political dimension of his new gig and his relationship with de Blasio. “I’ve worked with the mayor now for the last two-and-a-half years, and – not always in total lockstep, but I think that’s what I do well and I know that’s what the mayor does well, and that’s – to come up with some, sort of, decision that’s good for the city and good for the future of this place. So, I think, moving forward, I know we’re going to be able to work together and just make this city an even greater place.”

Those moments in past when de Blasio and O’Neill weren’t in lock step weren’t public. The ones in the future probably won’t be either. For a mayor whose stature has fallen and must soon define himself to a very skeptical electorate, that is probably a good thing.

One thought on “Bratton’s Departure Means De Blasio Owns NYC Policing Policy Outright”

Ultimately O’Neill must follow the inept deBlasio’s orders.