Guglielmo Mattioli

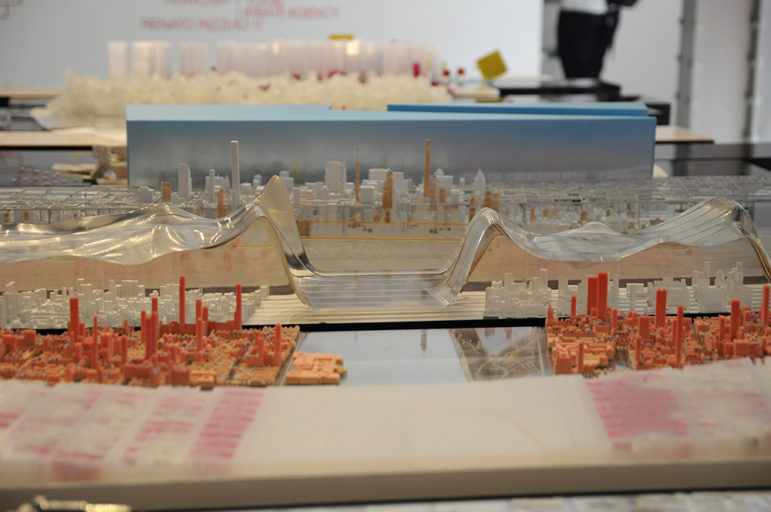

The waves in this installation by SITU represent the gap between recent sales value and property-tax assessments across a rich vein of the Upper West and Upper East sides.

The new luxury towers dotting the skyline of Manhattan have spurred concern among housing taxation experts and architecture critics on how little in tax revenues these properties generate despite their astronomical market values.

The problem has less to do with this new typology of residential towers–as controversial as they might be–and more with the system the city uses to assess and calculate property tax in general, which is so complicated that even experts have trouble understanding.

But a recent architectural model and a series of drawings effectively show the gap between properties’ real market values and relative tax liabilities.

SITU Studio, an architecture firm based in Brooklyn, came up with the idea to visualize this policy issue for “Sharing Models: Manhattanisms” a collective exhibition organized by the Storefront for Art and Architecture in which 30 architectural firms were each assigned a section of Manhattan and asked to produce a model of their own visions for the city’s future.

Inspired by the 2013 report “Shifting the Burden: Examining the Undertaxation of Some of the Most Valuable Properties in New York City” by the Furman Center, which cast a light on “the severe and persistent undervaluation of some of the most valuable co-op and condo properties in the city,” the Brooklyn-based SITU decided to focus on property tax disparities. Their project is named “Section 581” after the section of New York State’s tax code governing how property values are assessed for taxation purposes.

The current taxation system dates back to a real-estate market that was completely different from today values and was designed for a city facing completely different challenges.

“The city was really at is lowest point and the city’s government felt like it had to bribe people to build new units,” says Howard Husock, a housing analyst at the Manhattan Institute. “If you don’t incentivize developers, pretty soon you are Buffalo or Detroit.”

On top of the existing problems with the tax system, there was a decade of incentives and tax abatements to support new developments during the Bloomberg administration that produced a swath of luxury towers that are now benefitting from the outdated, arcane system.

An attempt at reform, gone wrong

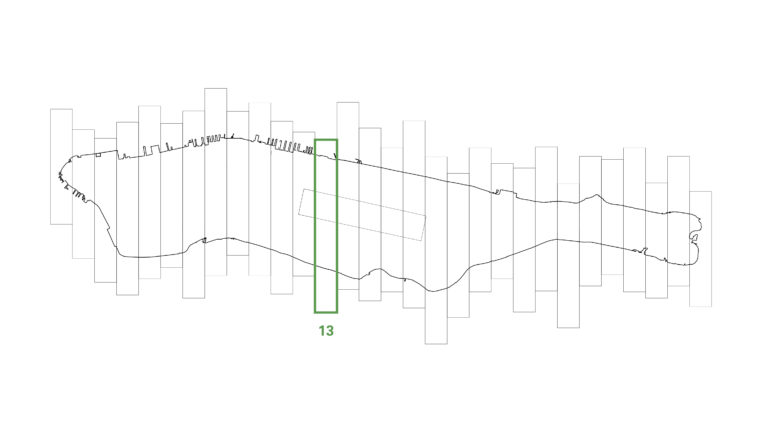

SITU

The swath of Manhattan studied by SITU.

The main problem is in the methodology the city uses to assess property value, found in section 581 and created by state legislation in 1981. It’s hard to believe, but the law was originally intended to fix unequal burdens among property owners.

Back in the 70s homeowners paid property taxes equal to a relatively small share of the value of their homes and owners of commercial and apartment buildings paid taxes based on a far larger share of market value. Furthermore, “owners of similar homes in different neighborhoods in the same town often had very different tax burdens,” read a 2006 report by the Independent Budget Office. “New York City homeowners in low-income communities frequently had a higher effective tax rate—the tax paid on every $100 of full market value— than homeowners in wealthier neighborhoods.”

To fix the problems the legislature came up with the idea of dividing all properties into four classes. Each class would be taxed on a different share of its market value. To protect owners who couldn’t keep up with growth in real-estate values, caps on annual assessment increases were introduced. Also to lower their burden, condos and coops would be assessed with a comparison system. The city would identify an equivalent rental property, which typically have many units that rent stabilized, to compare the condo or coops and determine its values.

This system, although pretty complicated, made sense back in the days. But it doesn’t work now.”Today it’s a very different world,” says Andrew Hayashi, a professor at University of Virginia School of Law and coauthor of the 2013 Furman Report. “The main problem with the current system is not so much the general level of property taxes in New York City but the big disparities you may have in property types.”

A 2006 IBO report indicated that over its first 25 years of operation, the 1981 law did shift the burden—but in a way that increased disparities. It also made accurate re-assessments of value difficult because of the annual caps, and effectively lowered the burden of condos and coops, especially in wealthy neighborhood, while the effective tax rate stayed relatively high in low-income neighborhoods.

Since the 2006 report, the disparities have reached new heights in the new super tall and skinny luxury towers. And one thing the 1981 law certainly didn’t do was make the system comprehensible to the people paying taxes.

“It is so complex… that it is impossible for the typical taxpayer to understand how her tax bill was determined. Even those of us who work on it for a living have a hard time following all of the moving pieces,” said George Sweeting from IBO said at a January public hearing.

A rising wave

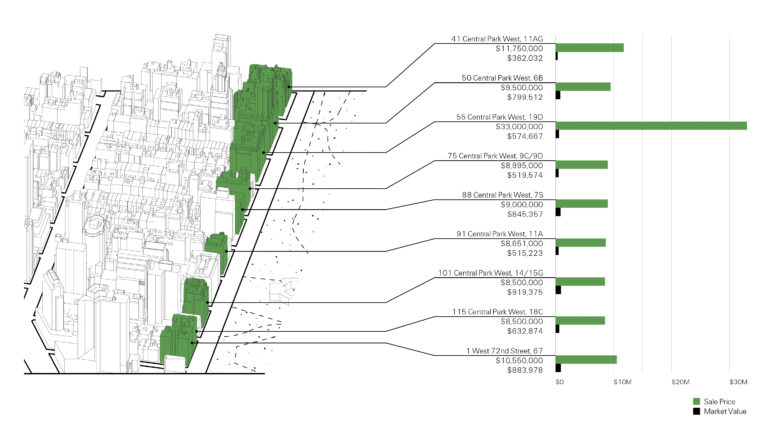

SITU

Sales value versus assessed value for some select properties in the section of Manhattan studied by SITU.

The SITU model uses architectural and visual language to show something that otherwise would be too hard to grasp.

A translucent acrylic surface, like a wave slowly rises from the edges of the model, peaks on top of the buildings with the higher discrepancies rates to dramatically fall flat above Central Park.

“We saw this as a chance to create a tool to open up a really complex policy issue and make it visible to a broader public” says Amy Parker, communication manager at SITU.

The model demonstrates in a visual and physical form some of the key findings of the 2013 Shifting the Burden report but uses the most updated information on property assessment roll from open data reporting by the Department of Finance and the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications.

“We are interested in taxation and luxury development because it has become an urban issue central to the conversation on real estate in New York City right now,” says Dan Miller, researcher at SITU.

The SITU model focuses specifically on a rectangular section of Manhattan, river to river, that goes from East 79th street to West 62nd embracing the richest parts of the Upper West and the Upper East Side, an area where the gap between market values and property taxes is vast.

The model and drawings show that high discrepancies between market value and taxable value exist not only among new luxury towers, but also in prewar buildings that have never been re-assessed to gauge current market values. For example, 55 Central Park West, a coop building erected in 1929, was last sold for $33 million in 2013 but the city still has it assessed at $574,000, making this apartment the one with the highest discrepancy factor in the section of Manhattan analyzed by SITU.

The new luxury towers, part of Bloomberg’s legacy, push the paradox even further. Max Galka, a data analyst working in New York, discovered that a penthouse sold for $100 million at One 57th street pays only $17,000 in property tax. “That’s an effective tax rate of just 0.017 percent (vs a national average rate of 1.29 percent),” he wrote on his blog Metrocosm. With more luxury developments on the rise, he says, “The whole problem is getting bigger and bigger.”

City Limits’ coverage of the intersection of art and policy is supported by the Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund.

One thought on “Not a Pretty Picture: Art Exhibit Depicts NYC’s Mountainous Property-Tax Inequity”

NYC Real Estate taxes are a mess to put it mildly. I pay about $5k/year on a 1-family home on SI valued at approx $500k. A Brownstone in Park Slope Brooklyn now worth in the millions can pay less in NYCRE taxes than I do. Crazy.