Office of the governor

Governor Cuomo tours Dannemora correctional facility shortly after the escape of two inmates in June. He and his predecessors have overseen a major reduction in the state's prison population.

New York State has slashed its inmate population by more than a quarter since its peak in 1999, from 71,538 to roughly 53,000 today, but the state’s corrections department budget has swollen by nearly a one-third in that time to close to $3 billion. This seems unlikely to change much either–in fact the budget went up last year, as did the number of unionized guards –and these trends could very well continue.

So much for the virtuous “justice reinvestment” cycle of taking money saved from expensive incarceration ($60,000 per inmate per year in New York State) and redirecting those public funds into communities to help former inmates reintegrate and keep youthful offenders out of ‘doing time.’ That’s not happening now. What small savings there have been occurred mostly on paper, costs avoided but spent elsewhere in the bureaucracy.

That’s discouraging because the state’s recent inmate reduction was the “easy” part of moving away from the heyday of excessive incarceration. It was largely accomplished by rolling back the draconian 1973 Rockefeller drug law, a move that the federal government is now largely replicating by releasing non-violent drug offenders, eventually tens of thousands of them. In New York, the reforms ultimately led to the closure of 13 prisons, where should have translated into real savings. Future reductions will be harder to come by, take more time and yield fewer if any savings.

“It is disheartening to hear that after the closure of these facilities there has been no commitment to re-apportion those desperately needed funds to justice reinvestment programs such as the anti-gun violence initiative SNUG,” says Assemblyman Walter Mosley of Brooklyn, who serves on the corrections committee. When set up in 2009 SNUG (guns spelled backwards) had $4 million of funding to allocate to community based organizations like Gangstas Making Astronomical Community Changes who, often staffed by former gang members, serve as mentors and “violence interruptors” for at-risk youth. In this year’s budget SNUG was given $2.9 million.

The rise and fall of the prison population

New York’s prison boom got underway in the 1980s when the state built 30 new correctional facilities. Prevailing high crime – mostly drug-fueled – and harsh statutory sentencing ranges quickly filled them; the inmate population swelled from 30,000 in 1983 to 64,000 by 1993. This occurred mostly under Gov. Mario Cuomo, who some say, felt compelled to be tough on crime and big on prisons to fend off fierce criticism of his opposition to the death penalty. The Department of Correction and Community Supervision (DOCCS) budget swelled to become one of the largest of any state agency and now consumes 60 percent of all Albany’s spending on security, with the balance divided up by 12 other agencies, including the state police.

When the state realized how fiscally unsustainable its over-built prison system had become it amended the Rockefeller drug laws three times and allowed the release of non-violent drug offenders. “Although it was not specified in the legislation—this was not a bill on closing prisons, but about reforming the Rockefeller drug laws—reallocating funds was very much part of the thinking behind it,” recalls Assemblyman Joseph R. Lentol who has had a role overseeing criminal justice matters for much of his Albany time since first elected in 1972.” We were well aware that reducing the number of incarcerated would allow funds to be freed up in the short-run and longer term there was the expectation of additional savings because the reforms would help close minimum and medium security prisons.”

Kenneth C. Zirkel

Mario Cuomo in 1987. Prison populations swelled dramatically on his watch, then began to recede under Govs. Pataki, Spitzer, Paterson and Andrew Cuomo.

But real savings have been elusive. The reasons are many. Even after the incarceration trend reversed course—more than 18,000 people were released between 2000 and 2014—scandalously under-used prisons remained open for years. Complete prison wings laid empty, but it was only when an entire prison could be shuttered that there was any promise of getting significant savings. After considerable political haggling, resulting in the creation of a $50 million fund for communities facing closures to “transform their local economies,” the state has managed to close 13 facilities in the last decade, leaving another 54 in the state prison archipelago.

DOCCS now boasts of saving $162 million annually from those closures. That’s less than Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s 2011 promise of $182 million from reduced operating expenses, and a negligible savings in a $2.647 billion budget despite a 26 percent drop in inmate population. Lentol notes, “It certainly looks bad, but imagine what the budget would have looked like if there had not been those closures.” And it appears those savings have been subsumed in the overall operational expenses of the prison system.

“Justice reinvestment has worked in places around the country [but] it requires a bipartisan agreement to be enacted and that has never existed on New York State,” laments Assemblyman Jeffrion L. Aubry, Speaker pro tempore. “Sadly partisanship has prevented its implementation.”

Where the money went

Assembly Daniel O’Donnell, the corrections committee chair, who is making a point of visiting every prison in the state, seems to accept DOCCS’ explanation that the savings from shrinking the prison population are meager – a mere rounding error in a nearly $3 billion budget – mainly because the shuttered facilities were all minimum or medium security, not the more expensive maximum security prisons. The number of correction officers employed by the state has dropped 14 percent since 1999, but that’s substantially less than the 27.5 percent decrease in the inmate count.

Inflation obviously plays some role in propping up the DOCCS budget despite inmate reductions. The more basic reason for rising costs despite a declining number of “clients” is that running an extensive prison system is becoming more expensive, especially as aging inmate population, needs more medical services and rising pharmaceuticals. Health serves have far outpaced any other normal inflationary driver, with those expenses nearly doubled in the last decade.

Marc Fader

Bedford Hills Correctional Facility

The even bigger expense and reason for the budget’s growth is staffing. Overall DOCCS has 28,919 employees – 18,988 are actual correctional staff. Others supervise the swelling ranks of parolees. Staffing eats up 61 percent of funds. That, in part, reflects New York’s “direct supervision” prison model, considered a progressive reform in the 1930s, where staff are in amidst inmates versus the ‘farm model’ in the South or the indirect model in, say, California, where a slightly larger correctional staff manages more than twice as many inmates – some 30,000 ‘peace officers’ for 130,380 inmates; think of guards with shotguns on catwalks above large prison yards. This current year Albany appropriated $112 million more for DOCCS – to hire 98 additional correctional officers (COs) and a sergeant according to the guard’s union – to cover negotiated salary increases and an additional pay period.

Still, one can wonder why, despite New York disgorging more than 18,000 inmates, there has not been anything close to a commensurate drop in correctional staff. Guard staff has been reduced at about half the rate as the number of inmates has dwindled. Between 2002 and 2014, while the inmate population declined by 14,501, correctional staff declined by only 2,315 in this October 2015, according to DOCCS data. That has seen the inmate-to-staff ratio slide from 3.2 to 2.8; in federal prison the ratio is closer to 5:1.

And a well-funded and highly organized union wants to maintain that trend. “These are great, living-wage jobs in an area like Ogdensburg, in an area like Lyon Mountain, in an area like Lake Saranac,” exclaims Mike Powers, president of New York State Correctional Officer and Police Benevolent Association (NYSCOPBA), which represents 26,000 officers and retirees, most of whom live upstate, around or above the New York Thruway where there are few other well-paid jobs not requiring higher educational levels.

He makes no apology for aggressively working to retain as many of those posts as possible. Powers, a 24-year DOCCS veteran, won a three-year term last summer as union president successfully by fending off the closure of the (787-bed medium security) prison in his home town of Ogdensburg (pop. 11,128 in 2010 census) on the St. Lawrence River border with Canada. The only other major employers in town, he notes, are a hospital and the school system. One of his top concerns: keeping up with attrition to maintain staffing levels. DOCCS’s peak hiring years were 89-91, leaving some 4,000 COs soon eligible to retire. The governor’s recent assent to a second training academy will help, he says.

Right-sizing the staff

Another expense offsetting savings from prison closures, inmate reduction and staffing cuts is a steady increasing in correctional overtime. The State Comptroller office’s recently found DOCCS was the biggest user of overtime among state operating agencies – spending $180 million last year (there go the $162 million savings from prison closures!). That was 27.2 percent of overtime earnings of all state agencies. Last year corrections overtime earnings rose 12.3 percent, continuing a steady trend that has seen its overtime earnings spike by 94 percent from 2009 to 2014. From 2007 to 2014, Corrections racked up $972 million in overtime earnings, nearly a quarter of the state’s overall OT spending of $4.1 billion during that period. Guards’ average overtime pay is $51.60 per hour, higher than any other state agency except the state police, and an average of 14 overtime hours per two-week pay period, yields $17,000 extra income per year.

Republican State Senator Patrick Gallivan, chair of the Crime Victims, Crime and Corrections committee, argues that DOCCS’ large overtime bill actually proves the prisons are understaffed, a position that echoes NYSCOB’s position. DOCCS Acting Commissioner Anthony Annucci recently set overtime targets for each facility and program and now requires superintendents to justify overtime expenditures to him personally via quarterly video conferencing. The Assembly’s analysis of the most recent executive budget said that there would be $31.6 million in savings related to “reduced overtime and vacancy controls” to partially offset the $112 million this year’s increase.

In NYSCOPBA’s lean-forward approach to expanding or preserving jobs no prison closure seems justified – because prisons are treated as synonymous with public safety. “The closure of any prison in New York State represents a significant threat to the integrity and safety of the New York State prison system,” argued Donn Rowe, former union boss, even when there were 8,000 empty beds.

In the midst of acute state budget deficits, Rowe appeared before legislators to argue: “While all deficits must be taken seriously, this shortfall simply does not warrant the hardship that would fall on so many New York families if these [prison] closures were to take effect; we owe it to them – some of New York’s hardest working public servants – to find alternate solutions to this year’s budget challenge.”

Current union boss Powers says there is “no [appropriate] price tag on safety.” Says Assemblyman O’Donnell, “I keep telling them it is not rational to expect more jobs when prisons are being closed but they get incensed when they hear that.”

So, even though Cuomo has said prisons are not an economic development model they are, in fact, just that: vital anchors for dozens of poor rural communities around the state without better prospects. “When you lose a $30 million payroll in an economic deprived area, imagine what it does after that, when that’s gone,” asks Powers. When Glenn Martin, now a criminal justice reform advocate who now leads JustLeadershipUSA. Back in 2000, as he was leaving Attica prison after serving six years for robbery, a correctional officer thanked him in a way he will never forget: “He said my being there helped pay for his boat, and that when my son came there, he would help pay for his son’s boat.”

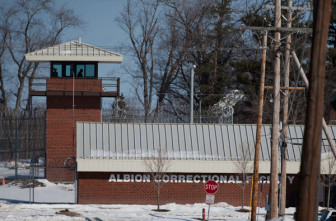

Marc Fader

Albion Correctional Facility

A sharply honed focus on its members’ interest – together with a budget of $5 million a year invests NYSCOPBA with considerable political heft. That’s grounded in upstate Republican legislators among whom O’Donnell says there is “tremendous opposition” to any further reduction of correctional spending or closing of facilities. In the past five years, the union and its associated political entities have donated more than $1.5 million to candidates around the state, including $205,000 to the state GOP apparatus, more than $70,000 to the state Democratic organization and $25,000 to then-Attorney General Cuomo in 2010. “They [NYSCOBA] are certainly a force to reckoned with because there are many, many, especially Republican, senators who have prevented the [prison] system from being right-sized for a long number of years,” says Lentol.

Nor are corrections officers shy about flexing their muscle when they feel threatened. When then-Governor Hugh Carey challenged seniority rules, COs went out on strike for two weeks – in violation of the Taylor Law – forcing a call-up of the state’s national guard.

Powers acknowledges that many poorer upstate communities lobbied Albany to have prisons built in their backyards (or have former asylums repurposed as in Ogdensburg) but denies there is any conflict with good public policy. “We are not in the warehousing business and we are not promoting mass incarceration of any type, nor would we ever, its archaic to even think it,” says Powers. “But do they [prisons] have an economic impact especially in deprived areas – anyone who says no, I’d like to have a talk with them.”

Despite some 5,000 empty beds (O’Donnell says that a prison and a half) and declining inmate count, NYSCOBA reports that the governor has agreed to order no more prison closures until at least the end of 2016. “State prisons are filled with very dangerous people. They are policed by a relatively small number of correctional officials, who are unarmed, I might add,” Cuomo said an event commemorating the Sept. 11 attacks. The governor said correction officers have a “very difficult job” in which they “have to make sure they get a certain amount of respect … Otherwise they get hurt.” NYSCOPBA recently trumpeted to its members the “unprecedented role” the union has won to work closely with Corrections Department in a sweeping security review throughout the state’s penal system and it urged its members to highlight security concerns. Indeed, the union’s press releases are a stream of accounts of inmate-on-staff attacks.

Changing dangers?

Still, NYSCOPBA’s client base does seem likely to shrink in the coming years, if some broad trends continue. These include declining crime rates and alternatives-to-prison policies, as well as shortened sentences. New York City, in particular, is sending fewer of its youth to do time in upstate prison. That’s the result of changes in police practices as well as a range of up-front investments; while the state cut SNUG funding, the city ponied up close to $16 million this year because of encouraging progress.

If these trends continue, it’s possible for the state’s inmate population to be cut to 40,000, says former New York City Corrections Commissioner chief Martin Horn within a decade. “Changes in law, in police practice and crime have already occurred so there social forces at work that nobody can control, what NYSCOPBA can control is whether prisons close or not – they can’t control what the inmate population is so we may find ourselves with empty prisons that are fully staffed.”

Powers says prisons nowadays are more dangerous environments because today’s inmates are younger, more violence-prone, often a gang member. The availability of powerful synthetic drugs ratchets up the volatility, as does the fact that an increasing percentage of inmates have mental-health issues that COs have no training to recognize, much less effectively deal with. Currently, COs get 40 hours a years of training; Powers said that should be tripled to help them cope. More updated technology is another priority, including more cameras – which inmates have long favored.

Another problem has been the state’s effort to relieve overcrowding in maximum security prisons, where population has been at 120 percent of capacity until recently, by reclassifying the less dangerous inmates so that they can move to medium-security facilities where releases have made room. But Powers says this can easily make for combustible situations because you are shifting inmates accustomed to two-person cells and putting them in dormitory settings where there is more potential for inmate on inmate conflict. “It’s a recipe for disaster,” says Powers.

Adi Talwar

Queensboro Correctional Facility

The one point of general agreement – between corrections officers and inmate advocates – is that tensions are rising, dangerously, in state prisons. Beyond that point, however, the two sides seem to occupy alternate universes. NYSCOPBA sees their upright professionalism – for “care, custody and control” – under daily siege. Assaults on guards have soared 30 percent since 2010, they say. This is a central argument for even more staffing.

Inmate advocates, on the other hand, report a marked spike in inmate complaints about aggressive management from guards. A frequent complaint, for instance, is the stepped up use of up-against-the-wall ‘tap-frisks’, in which if the inmate so much as turns his head, this can provoke guards to take down the inmate – with this recorded as another inmate-on-guard assault.

This bewildering tale of two states, or at least two prison systems, may partly reflect the deep divide that has long existed between guards and inmates. Over 72 percent of inmates are black and Latino, mostly from downstate cities, while 84 percent of guards are white, the products of upcountry communities. The Correctional Association of New York, an independent prison watchdog agency, notes that there was not a single black CO at Clinton when they visited in August and last fall, while 53 percent of inmates there are black. Powers says he knows of two minority staffers there, but dismisses staff racial composition as an issue at all. “I don’t see any true, hardline racial issues that come across – I have never seen any of that kind of barrier, I have never been privy to any of that – we are charged to conduct ourselves to a higher level and 99 percent of us do that, He insists. “All BS aside I don’t hear much about that.”

The prison closures that have already happened in the state have reinforced this cultural disconnect. Virtually all of the closed facilities have been downstate. That helps keep guards closer to home but at the expense of making it that much more difficult for inmates’ families to stay connected – a key factor in post-release success.

Where the money didn’t go

The issue isn’t just that the corrections budget has not yielded any ‘justice reinvestment dividend’ – wasn’t it bureaucratically naïve to have expected that? – but it is also how those monies are being spent. According to the Correctional Association [of New York], an inmate advocacy organization founded in 1844, and invested with statutory authority to visit prisons, there are disturbing trends to Corrections’ spending priorities. In the very gradual if not stalled down-sizing of the prison system, security staff are the least affected, the association noted in testimony at the most recent state budgetary hearings held early each year. There have been more significant reductions in support staff, program services, and even medical staff, which have declined at twice the rate of inmate population reductions, than in security headcount.

Attica Correctional Facility

“Throughout our prison visits, we are finding vacancies in crucial medical staff, including doctors, physician assistant and nurses, and in turn complaints from incarcerated persons about both access to care and the quality of care received,” noted CA’s executive director Soffiyah Elijah in her Albany testimony earlier this year. And while she commended the current year’s slight uptick in funding for programming, it is still 30 percent less than it was just a few years ago, resulting in “a tremendous number of program staff vacancies, long wait lists to get into basic mandatory programs, and a lack of programs other than the most basic mandatory requirements to help empower incarcerated persons and help prepare them to successfully return to their home communities.”

Also starved for funding are the legal mechanisms that assist inmates in asserting their rights. The Prisoners’ Legal Services of New York was set up in the wake of the 1971 Attica uprising, the bloodiest prison confrontation in U.S. history in which 43 people were killed (mostly from law enforcement bullets) after then-Governor Nelson Rockefeller ordered a forcible re-taking. The disturbance occurred because there was no way to air grievances and no access to legal counsel, a function PLS was meant to address.

When the PLS opened its doors in 1976 funding sufficed to have a lawyer for every 450 inmate. But as the work load has grown and funding stagnated – there are three times more inmates, half the number of staff attorneys – each lawyer handles 5600 inmates. If the original funding had kept pace, the PLS budget would be $16 million; instead it got $2.2 million last year.

“For me to have to go to the legislature every year, hat in hand to beg for enough money to do the job the state has asked us to do is very, very frustrating,” says PLS’ executive director Karen Murtagh. “If the state wants us to do a job, which to make sure there is never another Attica, to be a safety valve for our prisons, then the state needs to fund us adequately.”

That’s why even small amounts of savings from DOCCS – and recirculated as ‘justice reinvestment’ – can make an important difference: social service staff, legal representation, even post-release services for former inmates. Martin Horn, the former NYC Commissioner of Corrections and Parole, emphasizes the heightened need for funding of post-release services, lest the state repeat the mistake when it de-institutionalization tens of thousands of mentally ill people in the 1970s and 1980s.

Another key post-Attica reform was the establishment of inmate liaison committees (ILC), to gather inmate complaints and relay them to prison management and to regulators and watchdogs. In a recent letter from the Clinton ILC, addressed to the state’s Inspector General obtained by City Limits, the prison is reported to be “on edge and tensions are high” because of continued assaults on inmates by staff in side rooms and out-of-view hallways.

Guards are also alleged to be destroying inmate letters to the ILC, and the committee asked to meet with the state’s Inspector General when the IG conducts its post-escape investigation. “We are merely convicts, but even we can see the clear and present danger which exists at this facility and we sincerely hope you will not turn a blind eye towards this letter and its contents,” said the July 12 letter.

To Murtagh, the letter was “eerily reminiscent” of correspondence Attica inmates sent Governor Nelson Rockefeller months before the uprising – which went unanswered, except by force.

6 thoughts on “NYS Prison Budget Climbs, Despite Fewer Inmates”

nice piece . Please read my new book. Anthony

Papa is the manager of media and artists relations for the Drug Policy

Alliance. He is the author of This Side of Freedom: Life after Lockdown.

I don’t suppose the immense amounts of featherbedding has anything to do with this?

Job sharing? As an example, one CO sharing his job with another, works 2 double shifts, has 4 to 5 days off and still receives full wages and benifits without physically working those hours.

Imagine having off 5 days, getting vacation credits (and all the other benifits) and tacking on another week or two on top of that for a payed for vacation without performing any actual work. Sounds sweet. I won’t mention night shift not actually doing rounds because they know that the prisoners are in a particular place and do all the paperwork at the beginning of the shift without actually doing the actual round. Oops, just did.

Well… Lets correct your statement you made. First… Job Sharing. Yes, CO’s can “Job Share” but the correct term is Swap. Swaps are permitted in Corrections. A CO can work and 80 hour week and take the next week off. Example. CO Bob working Unit A works Monday to Friday 7-3. CO Joe works the same unit but 3-11. CO Bob agrees to work Monday through Friday for CO Joe’s 3-11 shift. CO Joe agrees to work for CO Bob’s 7-3 shift the following week. Paper work is submitted for authorization from staffing, then approved. In the 2 week period, both CO’s work there 40 hour week. Sounds sweet? Naaa. Your working the double shift so you can go home to your family 4 hours away on your days off. Now about not doing “Rounds” on the night shift. Does it happen? Sure it can. If you get caught not doing your rounds… instant termination. Not doing your paper work… well all paper work is time sensitive. Nice try Shark

At bare hill correctional, there was a c o they called sleepy,he’d do a head count an go right to sleep,then have an alarm to wake him minutes before brass would do there walk. It was crazy,inmates up doing whatever they want using drugs,sharpening weapons in shower. Brass knew what he was doing,they just didnt care. All officers stick together,its a joke. Ive seen inmates beaten in side hallways an corridors for doing nothing but facial expressions

Pingback: The Incalculable Costs of Mass Incarceration - Justice Not Jails

Pingback: Following the Money of Mass Incarceration | Exposing a multibillion dollar...