Adi Talwar

Clients at New Alternatives for LGBT Homeless Youth on Christopher Street gather for Sunday dinner in March. Street homeless are very hard to count, and young people living on the street are particularly elusive.

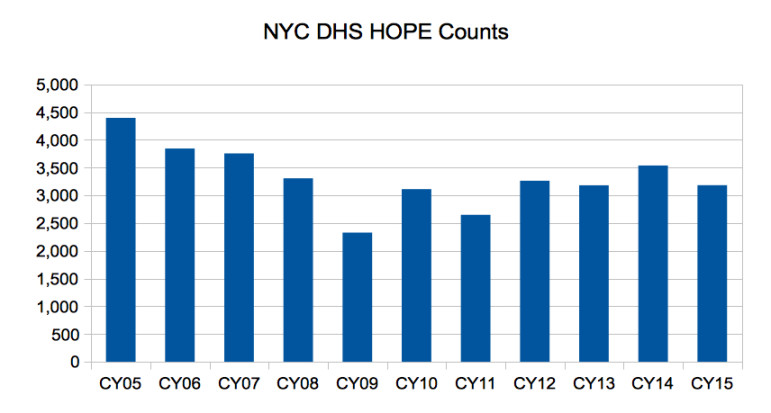

Through all the talk this summer of a new homelessness crisis in New York City— from media reports of rampant homelessness to rising vagrant-related 311 calls and a police union’s politically charged viral “quality of life” campaign — the official numbers stuck to their story: Street homelessness, according to New York City’s Point-In-Time (PIT) Homeless Outreach Population Estimate (HOPE), decreased five percent from 2014 to 3,182 in 2015, and is down from 4,395 a decade ago.

So which is to be believed: the HOPE data or the photographs, media reports, and complaints? Actual glimpses into the local street homeless population show a far more complex and obscure reality, one that many argue is critically underrepresented and misunderstood by snapshot efforts like HOPE or public perception.

New York, like cities across the U.S., is federally required to count street homelessness through the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) PIT Counts. They are a prerequisite for participating in HUD’s Continuum of Care (CoC) program— a network of local and nonprofit organizations that deliver and organize services to local homeless populations —or to apply and compete for billions of dollars in HUD Homeless Assistance grants.

After HUD launched its first national PIT count in 1983, New York soon became a pioneer—along with Philadelphia, it was one of the first cities to require the collection of client-level data from local homeless shelters. Today, HUD regards New York’s HOPE count as a “gold standard,” because, among other factors, it is held annually instead of biannually — the minimum HUD requirement — and employs a “shadow count” in which decoys are placed in canvass areas to test each tally’s accuracy.

And like all PIT counts around the nation, New York’s HOPE’s results are pivotal to federal policy. PIT numbers are the basis for HUD’s Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress, and were the premise for the federal government’s “Opening Doors”2010 strategic plan to prevent chronic homelessness, the first ever of its kind.

Yet HOPE is known as much for its praise as it is for rebukes over its methodology. A lot of the criticisms however, are about features that HUD, not the city, imposes—like that requirement to hold the count only during one night at the end of January, instead of during the summer when many argue there is more street homelessness, and to disqualify any homeless person who says he is doubled up or couch surfing on the night of the count.

Benjamin Charvat, the New York Department of Homeless Services’ (DHS) Deputy Commissioner for Policy and Planning, dismisses the widespread criticisms of HOPE as a misunderstanding of the point and scope of the count.

“The reasons we don’t do the PIT count in the winter is both because of the HUD requirement and because it is the most accurate count of the most vulnerable – the people who have nowhere else go to as opposed to those who can find short-term or temporary housing.”

But it is this circumscribed scope that leads many to attribute a certain arbitrariness to PIT numbers — numbers that, despite being obtained through a consistent methodology, only ranged from 2,328 to 4,395 over the past decade and don’t readily correlate to economic trends, like recessions, or to the local homeless shelter population numbers.

The Kids Aren’t Alright

The arbitrary nature of PIT counts is especially clear when one looks at DHS’s efforts in recent years to count a particularly elusive and vulnerable group, homeless youth.

The demographic was the focus of the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and HUD, which in 2013 jointly launched a Youth Count, a pilot program designed to access and develop effective methods to count street homelessness among youth aged 13 to 24 across nine communities, including New York.

The local Youth Count 2013 required HOPE canvassers to document the age of those surveyed and opened 14 Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD)-funded drop-in youth shelters during the same night as HOPE, where youths could fill out a 27-question survey in exchange for MTA Metrocards and food. Of the 182 participants who dropped in, only 132 met the HUD definition of homelessness. (Another 128 youth were counted by the separate HOPE survey).

The numbers of homeless youth documented by the 2013 effort were far smaller than the only other statistic known to have been generated on the population— the Coalition for Homeless Youth’s 2007 count, which enumerated 945 homeless youth and estimated at least 2,841 city-wide. It involved canvassing over many days during daylight hours in summer months and expanding the definition of homelessness to include the temporarily sheltered, like couch surfers.

The great discrepancy between the figures on homeless youth, says James Bolas, Executive Director at The Coalition for Homeless Youth, belie the reliability of PIT numbers. “I would seriously be skeptical of any cases of youth homelessness that doubled from 2012 to 2013 or dropped from around 3,000 in 2008 to 128 in 2013.”

The problem with PIT counts stem from the fact that “youth are counted differently,” he explains. “They are much more mobile, especially in the middle of January and February during 10 p.m. to 4 a.m. when it’s cold — they are going to find, and they are going to negotiate, a place to stay. To count a transient and largely invisible population – invisible mainly due to self-preservation– well, you are not going to find it as easy.”

Stephanie Gendell, Associate Executive Director for Policy and Government Relations at the Citizens Committee for Children, says homeless youth are simply hard to count. “Aside from sleeping on streets, subways and in youth shelters, homeless youth often couch surf and unfortunately sometimes engage in survival sex. And youth out in New York can easily blend in with their stably sheltered peers—there is no way to know for sure whether a young person out in McDonalds, Union Square, or other places youth congregate has a place to live without actually asking them.”

A class action lawsuit filed against New York City in December 2013 sought to force the city to provide more shelter to homeless youth, a population it argued was around 3,800 a night, with shelter beds numbering around 250. And in a sign of an ongoing shortage of services, one of the largest young shelters in the city, Covenant House, recently admitted turning away around 75 youths per month due to lack of space.

PIT Politics

Yet much to the chagrin of homeless service providers, PIT numbers and PIT methodology are still regarded by city officials as main standard in determining the extent of homelessness and needed services in the city.

“The PIT HOPE count comes from the idea, and is essentially a component of, a cost-benefit analysis: ‘in order to figure out how to fund this population, we need to count them,’” says Bolas. “And there has been a huge reliance on this PIT tool as this ‘answer’, but what it does is shoot us in the foot.”

Like crime statistics, the HOPE figures have gone from being a useful tool for policymakers to being a political football. When pressed on local vagrancy, former Mayor Bloomberg, for example, once infamously declared: “Nobody’s sleeping on the streets,” a statement his administration quickly attributed to his rounding down from the 3,262 that HOPE counted for 2012. The Bloomberg administration was also given to routinely touting declines in HOPE numbers — even in times of deep economic recession — as proof of tangible progress in dealing with street homelessness.

DHS

The de Blasio administration hyped the good news in the 2015 HOPE Count.

More recently, the De Blasio administration used a similar defense— citing the decrease in 2014 HOPE numbers to push back on claims the city had a growing homelessness problem. It wasn’t until after De Blasio declared the much talked about homelessness problem in New York a reality, one he described as “historic”, and “decades old,” that he finally noted that the street homeless population was likely to have “grown a bit over the summer” from the year’s HOPE estimate.

A different HOPE would not be easy to create: Some changes would require federal approval. Some aspects of the survey are the city’s decision. There, the city opposes any change.

“We don’t go into private areas because it would be very annoying to a business owner, and some locations like ATMs are unavailable to go in,” explains Charvat. “We are also responsible for the safety of all our volunteer canvassers.”

Bolas, however, disagrees, arguing that any annoyance is minimal and that such an effort is not only possible with the right logistics and preparation, but necessary as well.

The count as outreach

“Maintaining the safety of canvassers comes down to adequate training and teaming — don’t send inexperienced individual members into risky neighborhoods,” he says. “This is important because while HOPE canvassers are not doing outreach per se, they are engaging people directly in asking intimate questions.”

Engagement was key to the 2013 Youth Count, which in part showed the value of surveys not so much at determining the absolute number of homeless people but at learning things about the population that can help policymakers shape responses.

“I think that despite the methodological issues with the 2013 Youth Count, we learned a lot of information from the survey of the homeless youth,” says Gendell. “While it was only 132 young people, it was a 132 youth telling us where they stayed, what their needs are, and how the City could help them. In that sense we got extremely valuable information out of it even if we didn’t get the exact number of homeless kids.”

DYCD used the findings from the 2013 Youth Count to improve the methodology and reach of the most recent iteration of the Youth Count, which took place during the 2015 HOPE Count.

“The lesson learned from the experience was that unless the site is somewhere that youth frequent naturally, there wasn’t great likelihood that they would go there on the night of the count,” says Mark Zustovich, a spokesman for the city’s Department of Youth and Community Development.

And it paid off: According to a preliminary report, 857 youths dropped in to take the 2015 Youth Count survey. The effort still fell offered a narrow snapshot— while it took place over the course of four days, it only counted youths who were homeless on the week’s Monday night, during HOPE count, meaning that only 68 youths met HUD’s PIT definition of homelessness. The other 789 surveyed were either transitionally sheltered, couch surfing, or trading sex for shelter on that Monday night.

This time, however, advocates do report an improved exchange of information between critics of the DHS counts and the agency.

“One of the things we’ve done better this year: There has been an increase in relations between the researchers and the homeless youth population and providers,” says Bolas. “What we needed really happened: for local government officials to listen to the population. And frankly, we were a little shocked that there was this government response of: ‘We really want to work with you’. It was a huge relief for homeless youth providers.”

City Limits’ coverage of housing policy is supported by the Charles H. Revson Foundation.

* * * *