DHCR

New York City’s politicians have long chattered about creating affordable housing at the same time that they have let the number of rent-regulated apartments plummet. Mayor de Blasio has expressed somewhat more interest in this problem than his predecessor and an important place for him to look for a solution is the NYS Division of Housing and Community Renewal (DHCR).

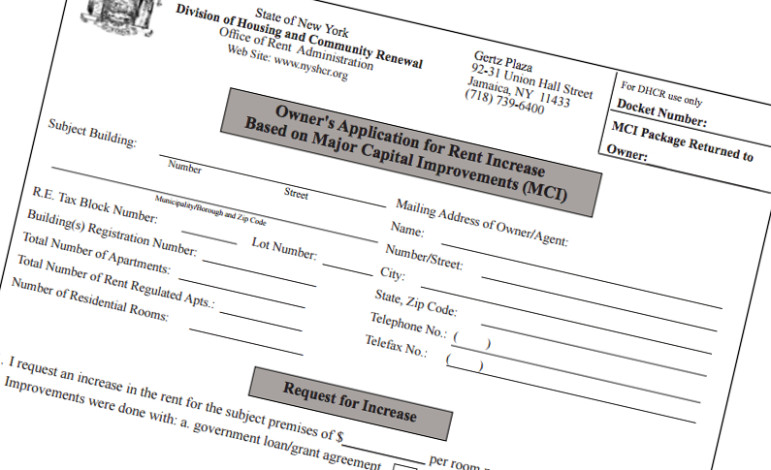

Among the responsibilities of the DHCR is “protection of rent regulated tenants.” In my extensive dealings with the Major Capital Improvement (MCI) division of this state agency, however, what it actually does is protect the very landlords who are sending city rents soaring. These MCI rent increases need great attention because they are permanent increases that force tenants to reimburse their landlords over and over again for one-time expenses such as installing a new boiler, or new windows, electrical rewiring or restoring a building’s facade. Nonetheless, the DHCR approves 90 percent of these increases, all the while accepting landlord’s self-serving testimony on the honor system basis; “good faith reliance” as the DHCR called it in Court testimony. Further, these MCI rent hikes increase even more every year due to their compounding in lease renewals.

But, it gets even worse. If MCI increases succeed in bringing your rent over $2,500 a month, you will be obligated to respond to “luxury decontrol” notices from your landlord every year, drowning you in complicated, poorly explained paperwork that may lead to your apartment going market rate. That means your rent could double or triple or more in the immediate future.

Lessons from experience

Twice in the past decade I have taken my landlord and the DHCR to NYS Supreme Court on appeal in MCI cases. (The DHCR is a state agency, not a “court.”) My first case concerned the fact that MCI work must be completed building-wide, in a single effort (regulations that exist in order to prevent landlords from passing along MCI increases every year). Even though my evidence made it crystal clear that my landlord had by no means met these core requirements, the DHCR did not “protect” me. Instead it attempted to keep my case out of the record based solely on legal technicalities, completely ignoring the merits of my case. It didn’t work. The Court remanded the case back to the DHCR and forced them to consider my evidence, and I won. My landlord had to write rent-refund checks for about three-quarters of a million dollars, ranging from $17,000 to $50,000 per apartment, and reduce rents throughout the building.

In my second case, I clearly proved to the DHCR that the MCI completion date my landlord repeatedly, emphatically claimed was incorrect, meaning he could by no means prove compliance with the mandatory two-year filing deadline. But the DHCR wanted to grant the increase anyway, so they created their own case on behalf of my landlord. On appeal, in what I consider a lazy, autoresponder decision, NYS Supreme Court Justice Alexander Hunter upheld the decision, relying on the ubiquitous cliché that cites the “expertise” of state agencies in making their decisions. The DHCR MCI division, however, has no architects, engineers or construction workers on staff, and therefore certainly does not have the expertise—and also lacks the legal authority—to override a landlord’s own testimony as to an MCI completion date or the construction event that marked its completion.

From those two experiences, here’s what I have learned about protecting yourself from illegitimate MCIs:

First, know the grounds for fighting MCI increases. When the DHCR sends notices to tenants about their landlords’ applications for MCI increases, they deliberately withhold everything tenants need to know about the legal grounds to respond to the notices to fight the increases. MCIs must be:

- building-wide

- completed in a single effort,

- on all same or similar parts of the building,

- to the direct or indirect benefit of all tenants

- and not due to delayed maintenance.

As throughout our legal system, lawyers get paid to manipulate such standards, and in this case the last two items on the list above are particularly vulnerable. So, unless there’s a tenant in your building who has a lot of time to spend informing himself about how to build your case, if you indeed have one, form a tenants’ association and hire a lawyer.

Second, supervise your lawyer. To fight our $77-per room increase (risen to almost $100 a room by the time the case was settled), the rent-regulated tenants in my building hired a lawyer. As that lawyer was about to lose the case for the third time (and did), I dove in and took the helm for the next six years, becoming a named party in the case. During those years, I was dismayed to find that I was the only person in the 60 affected apartments who was actually reading the filings—our lawyer’s, our landlord’s lawyer, and the DHCR’s lawyer. In fact, in my final submission in the case, I put into the record a document that was devoted solely to correcting the major errors in fact and major omissions by the tenant association’s lawyer in his own final submission.

To avoid having your case compromised by similar problems, here are some guidelines:

- Several tenants should volunteer to read all your lawyer’s filings before they are submitted to the DHCR or Court.

- Check the documents for accuracy and clear up any misunderstandings, omissions or wrong facts.

- Get explanations for the legalese and procedures you do not understand.

- Tell your lawyer to also give your volunteers copies of all submissions made by the DHCR and your landlord’s lawyer as he receives them.

- Check those documents for accuracy, too. Call your lawyer’s attention to any facts or arguments where you believe your landlord or the DHCR is misrepresenting the case: any substantiating evidence that is missing, exaggerations—or lies—and make sure your lawyer takes action on them.

Also, lawyers frequently ask for postponements of Court or agency appearances. Tell your lawyer you want to be informed about such requests, his (in advance), or opposing counsel’s or the DHCR’s. If your lawyer tells the agency or Court that he objects to a requested delay, they may deny the postponement. (Once, after my landlord’s lawyer caused a year-long delay in our proceedings, I called Sen. Liz Krueger’s office and asked for her intervention. It was just, yes, three days later that the case was back on the calendar.)

Third, remember there is no time limit on appeals. In the notices the DHCR sends tenants about the decisions they have reached, they also withhold the fact that there is no time limit on appeals in MCI cases—as long as there was no appeal to the NYS Supreme Court. (The DHCR has its own in-agency appeal procedure.) For example, say your landlord repairs deteriorating mortar between the bricks on the lower floors of your building facade (“repointing”) and testifies to the DHCR that the work was completed everywhere in the building that it needed to be done. The DHCR awards him an MCI rent increase. Then let’s say your landlord comes back two years later, or seven years or 10, and does the same work on the upper floors of the building. This gives you grounds to reopen the case on appeal to the DHCR and ask that the MCI increase be revoked on the grounds that the original work was not performed “building-wide,” in a “single effort” on all “same or similar parts.” (The DHCR has posted at its website the legal lifetime of each type of repair, often 25 years, so at least in theory you have up to 24 years to appeal.)

Room for improvement

Of course, tenants shouldn’t have to battle both their landlord and an unhelpful or antagonistic state agency. Not only does the agency withhold from the public crucial information they need to know about the legal requirements for MCI increases and appeals, the DHCR web site is too difficult and time-consuming to navigate to find reliable answers on your own. More important, landlords assume little risk in making exaggerated claims or even lying in MCI cases because penalties meted out by the agency are precious few. Remarkably, when the DHCR was finally forced to consider my evidence and revoke that big rent increase, their Revocation Decision stated that my landlord’s dishonest testimony merely “strains one’s sense of credulity.” What was the DHCR penalty to my landlord for misleading it for years about this huge increase? Nothing.

What was the DHCR penalty to my landlord for continuing to send High Income Decontrol notices to tenants whose rents were below the legal cutoff for these notices? Nothing.

Does the agency make routine site visits to buildings in MCI litigation to bring contested claims to a quick end, saving both time and taxpayer money? No. And on the very rare occasions that they do make site visits do they invite landlords and exclude tenants? Yes.

The DHCR also provides no oversight when landlords take vacant apartments market rate, also done on the honor system basis. This includes when landlords would need to demonstrate expenditures of tens of thousands of dollars renovating a studio or one bedroom apartment. In the case I won a few years ago, in its nine-year slog through the court system, 30 of the 60 rent-regulated apartments in play had gone market rate as the tenants passed away or gave up and moved away. But the DHCR never investigated whether all those apartments were legally taken market-rate, since the increase was retroactively revoked.

In its pro-landlord stance in MCI decisions as well as its failure to adequately supervise vacancy decontrol, the DHCR is a major participant in driving middle class families out of the city.

2 thoughts on “Tips for Tenants Battling Rent Increases in Court”

I am dealing with this stupidity right now, and its incredibly how obviously corrupted everything is, with no fix in place.

Affordable housing; What affordable housing!!. How about rent stabilize building. Government Cuomo made a law- that landlords can increase rent thru major capital improvements to the tenant. FORCED tenants to pay increase rent for their building. Theyre the only ones that benefit. Who ever heard tenants repairing somebody else property. It should be landlord. We got yearly increase and now MCI. Where’s the affordable housing in rent stabilize building. It got to stop. Im afraid that my children will not be able to stay in NEW YORK as well as others I dont think you can afford to have lots of people leaving new york its getting toooo expensive. And it’s all the government Cuomo fault MCI.