Melanie Bencosme

Juan Carlos Guzman didn’t find out about the 26-year-old error on his rap sheet until he was detained by immigration authorities on his way back into the United States.

Melissa wasn’t aiming terribly high: She wanted to be a substitute teacher in New York City’s school system, a job that would combine her passion for education with a decent paycheck. Yet her modest goal had to go on hold thanks to the inability of an upstate court to verify that her almost 20-year-old shoplifting arrest was long ago resolved when she agreed to spend 200 hours in community service.

Kevin Cleare, having served his time for a robbery committed while he was homeless, wanted a chance to go to school and train for a job. His ambition was thwarted as well when three open arrests—criminal encounters that never even occurred—somehow appeared on his official record of arrests and prosecution, or “rap sheet” as it is universally called.

The stories in this series were reported by Sarah Barrett, Melanie Bencosme, Rebecca Bratek, Laura Bult, Terence Cullen, Briana Duggan, Erica Edwards, Natalie Fertig, Frank Green, Rosa Goldensohn, Victoria Johnson, Caroline Lewis and Rikki Reyna. The project was conducted in a class on urban investigative reporting at the City University of New York Graduate School of Journalism taught by Errol Louis and Tom Robbins who served as editors with assistance by Jack D’Isidoro.

Then there’s Richard Norat, who decided after sitting behind bars for 20 years for crimes to which he pleaded guilty that he’d become an exterminator. That’s a trade that will always be in demand, he figured. It’s also one that requires a license, and when Norat looked at his own record of encounters with the criminal justice system, he saw a batch of crimes wrongly listed as open, even though they were all more than 20 years old. His cockroach-killing plan quickly stalled.

That kind of collision with faulty court and law enforcement record-keeping is encountered by tens of thousands of New Yorkers every year. They involve cases that should have been sealed, but were not; arrests that were voided but are still listed as active; warrants that were answered but somehow never vacated; and cases never pursued in the first place, but which stubbornly cling to records like old chewing gum.

They are mistakes that come with major consequences, frustrating the best efforts of people trying to turn their lives around, leading to rejections by schools, employers, lenders and landlords. And legal records are littered with them. By one estimate, an astonishing 2.1 million New York state residents have mistakes on their criminal justice histories, errors that must be painstakingly corrected one by one, in a complicated, time-consuming and sometimes fruitless effort.

A society that prides itself on the rigorous prosecution of those who break the law is stunningly slipshod and careless when it comes to keeping those records straight. That’s the finding of a team of reporters at the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism who spent three months interviewing people caught up in the trap of rap-sheet errors, those who try to help fix them and those in charge of the records themselves.

The investigation found that, despite the epic size of the problem, few funds are directed at correcting those record mistakes. There is also no clearly marked path to guide those attempting to do so. In fact, the agencies where those errors likely originated—police precincts, prosecutors’ offices and courts—are often not only unaware of their own role in creating those potholes, they are actively disinterested in filling them.

‘What are you doing here?’

When Kevin Cleare, accompanied by a paralegal from one of the few organizations that aid those trying to repair their records, went to police headquarters at One Police Plaza to try to track down the source of the mistakes, he was directed to an office that handles computerized arrest records. Officials there were baffled even at the nature of their request. “How did you get in here? What are you doing here?” they were told, recalled Sebastian Solomon, the advocate from the Legal Action Center who accompanied Cleare to the office. (See “The 7-Year Quest to Fix 1 Skewed Sheet.”)

Melissa has endured her own Kafkaesque journey through the bureaucracy. A Masters in education candidate at Columbia University, she knew that the city’s Department of Education meticulously examined the backgrounds of teaching applicants. With the help of her own guide from another group, the Center for NuLeadership on Urban Solutions in Brooklyn, she obtained a copy of her rap sheet. Although Melissa had been assured at the time of her arrest that the record would be sealed once she’d completed her community service, it was still there, minus any details on status or disposition. A call to a court clerk in Poughkeepsie in Dutchess County, where the arrest had been adjudicated, brought a reassuring response: There was nothing pending, she was told. So Melissa went ahead with her teaching application. A few months later, she was told she couldn’t qualify for a certificate. Her arrest was still open.

Erica Edwards

Melissa, who asked that her real name not be used so she can move on from the rap-sheet errors she has fought to correct, thought she'd taken care of a two-decade-old arrest for shoplifting. She was wrong.

Like many we spoke with, Melissa asked that her real name not be used. She did so for the simple reason that, if she can ever straighten out her arrest record, she’d like to put the episode permanently in her past, where authorities had long ago promised it would stay if she complied with the rules and did her community service. So far, she’s had no such luck. She’s made three trips to the Poughkeepsie courts, paying small fees on each visit to obtain copies of old records. None of them show the disposition of the case. Without one, the education department’s Office of Personnel Investigation won’t budge on her application.

Richard Norat had better luck digging his way out of the trap he found himself in after completing his prison term, but he needed a lot of help. His first post-incarceration job was with The Doe Fund’s Ready, Willing, and Able, a program that trains recently released convicts. When he described his career goal, job counselors directed him to the Community Service Society, which also aids those trying to correct criminal record errors. [CSS is a funder of City Limits.] Still, it took Paul Keefe, a senior staff attorney there, months of wading through old records, along with repeated visits to court to straighten out Norat’s rap sheet. When Norat presented himself in criminal court at 100 Centre Street, the judge looked at him askance when she saw his 20-year-old record. “What brings you back from the dead?” she asked. Keefe was able to obtain several more dispositions for cases that should’ve been logged as closed long ago, and forwarded them to state officials who compile rap sheets. Norat finally won his exterminator’s license in November.

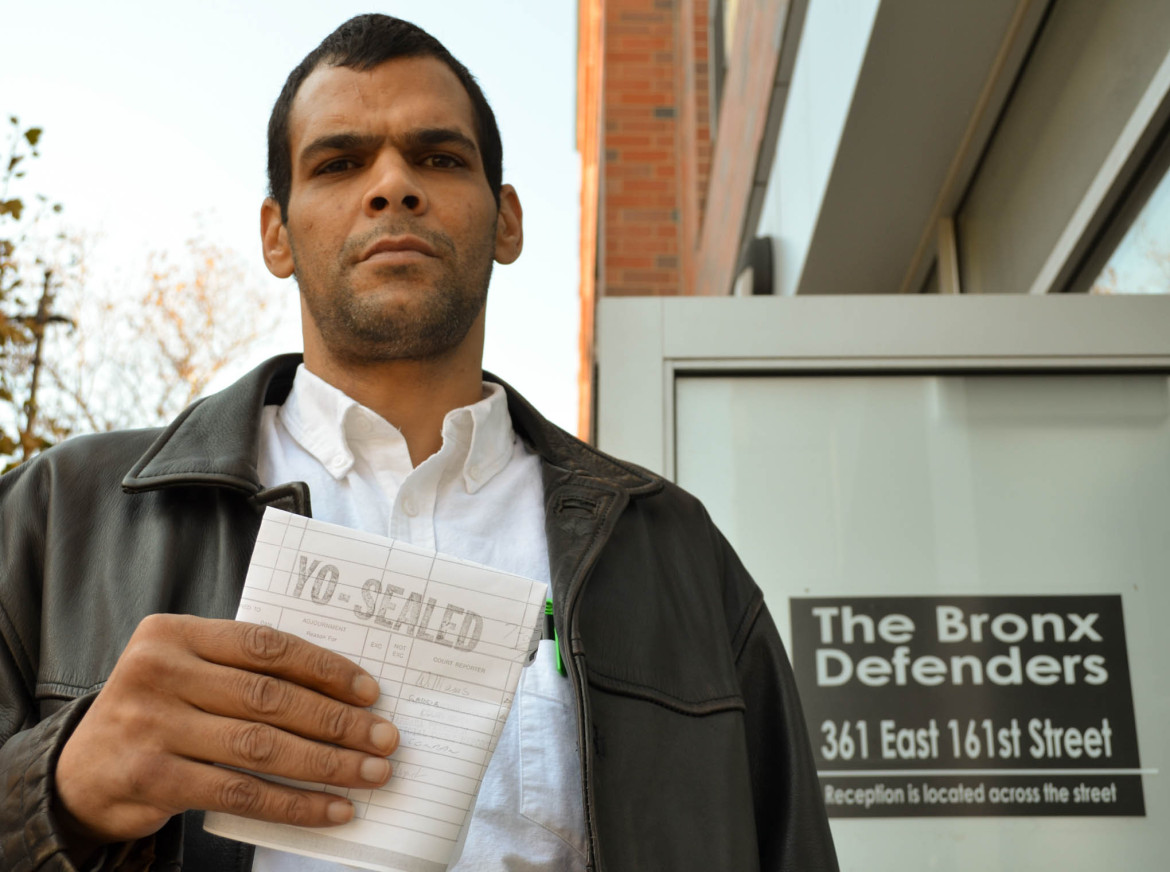

Most people don’t find out about rap-sheet mistakes until there’s a problem. That’s what happened to Juan Carlos Guzman when he returned in October 2013 to New York after visiting his native country, the Dominican Republic. Guzman, 40, had lived in the U.S. since the age of 9 and had obtained lawful permanent resident status. But immigration authorities detained him at the airport and held him for months thanks to a pair of outstanding robbery felonies that showed on his record. Guzman was 14 at the time he committed the robberies, and he served a year of incarceration to pay for his crimes. Since he was under 18, he sought and was granted designation as a youthful offender. A “YO” adjudication, as the designation is known in courtroom lingo, was supposed to be sealed. But when immigration officials looked, the old cases were listed as open. The culprit was likely simple human error, Guzman’s lawyer surmised.

“There’s an enormous amount of cases going through the system, and there’s one cranky clerk sitting there jotting stuff down on a folder,” says Jennifer Friedman, an attorney from The Bronx Defenders, a legal assistance group. “I think that’s how it happened.”

Clerks might have good reason to be cranky. State budget cuts have sharply pared the workforce responsible for handling court records since 2010. “We have fewer clerks and clerical personnel doing the same amount of work,” says Justin Barry, the chief clerk for New York City’s criminal courts. A budget report issued in 2013 by state court administrators noted that the cuts had resulted in “delays in processing court documents, frustrating the timely disposition of cases.”

In Guzman’s case, once the original records were dug out of the archives they showed that authorities had literally missed a red flag: Stamped on the outside of his criminal case folder, in big, bold letters, was a reminder: “YO Sealed.”

No one accountable

There is no precise accounting of how many records contain the kind of errors that sidelined Melissa, Cleare, Norat and Guzman. But each attempt to quantify them has arrived at astonishing figures. When the Legal Action Center examined 3,499 rap sheets of people who came looking for help in 2013, it found that 30 percent of them had at least one mistake; some contained several. If the percentage holds true of the 7.1 million criminal record histories generated by state agencies, that means there are some 2.1 million people with rap-sheet errors, the group found.

Sarah Barrett

Errors two decades old hampered Richard Norat’s hopes to build a new life as an exterminator.

But the number could well be higher. Youth Represent, a group that works with young people in both the criminal and juvenile justice systems, reported finding errors in more than one out of three of the 800 cases it examined in 2013. And a survey by The Bronx Defenders of its own clients found a higher error rate yet of 60 percent.

The vast scope of the rap-sheet errors dilemma became clear to Martin Horn when he served as New York City’s commissioner for correction and probation under Mayor Bloomberg. In that post, he regularly encountered people passing through the city’s criminal justice system burdened by inaccurate data on their records. The task of correcting them, he says, has long been an orphan.

“Nobody owns the problem, and no one is accountable for fixing it,” says Horn, who now teaches at CUNY’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “And pretty much the system says to the individual that it’s your responsibility to fix it.”

Indeed, efforts to get the key law enforcement players to discuss why so many mistakes slip through the system went largely for naught. Court officials referred questions to the District Attorneys; the DA’s directed them to the police. Inquiries to police officials went largely unanswered.

Part of that reluctance stems from the very abundance of people seeking help with rap-sheet errors: Officials are leery of getting overwhelmed by the afflicted. One lawyer who helps correct rap-sheet mistakes told about how, desperate to reach someone knowledgeable in the NYPD, she posted a pleading email to then police commissioner Ray Kelly on the department’s Web site. Eventually, a police official responded and agreed to help. But it was a one-of-a-kind arrangement. There remains no official mechanism for correcting errors stemming from police mistakes.

Even the few easy fixes that would bring relief for those who are dealing with decades-old mistakes have received short shrift from those with the power to change the system. More than 250,000 of the mistakes on criminal record histories are at least 15 years old, according to state statistics. These aging errors primarily consist of cases that were never prosecuted, or were dismissed, but never sealed. Some, like Melissa’s old shoplifting arrest, were resolved, but never properly recorded as such. Many date from as far back as the 1960s and 70s and are cases whose resolutions got lost as records were transferred from paperwork to computer data. A bill that would prevent those older and inactive cases from being included in the criminal record histories supplied to potential employers has failed to pass the state legislature in each session since 2009. So have several other modest legal adjustments advanced by a coalition of advocates trying to address the issue. (See “Legislature Falls Down on Fixes”)

Bult/Goldensohn

When Kevin Cleare and a paralegal went to police headquarters to try to track down the source of the mistakes, officials were baffled even at the nature of their request.

The advocates are generally the only ones focusing on the problem. The coalition includes those nonprofit groups shouldering the task of trying to help individuals repair their records, like the Legal Action Center, Community Service Society and Youth Represent. And those organizations do that work on a shoestring, cobbling together state grants with donations from foundations and money from the organizations’ own coffers to fund the lawyers and associates needed to pursue the cases.

Winning funding for any efforts aimed at helping those with criminal backgrounds is always an uphill battle. After years of pushing, groups helping formerly incarcerated New Yorkers find jobs and adjust to life on the outside won support in 2012 from the legislature and the Cuomo administration for a $12 million program to fund reentry training. But none of the funding was earmarked for fixing rap-sheet errors, even though the problem affects a wider swath of New Yorkers.

Organizations have had to be creative. For example, the Community Service Society’s Next Door Project trains older adult volunteers, many of whom hail from the same communities as the organization’s clients, to become adept at understanding often dense and confusing criminal record histories and how to correct them. The volunteers provide one-on-one assistance to clients. At the Legal Action Center, attorneys have resorted to bringing so-called “mass sealing motions” that cover dozens of cases at a time, rather than filing individual and time consuming actions.

Missing dispositions and wary employers

The extent of the rap-sheet trap faced by so many New Yorkers is no mystery to state officials who handle the records. All arrest information and follow up data in New York State is funneled through the state’s Division of Criminal Justice Services, the agency charged with trying to forge a coherent system out of data produced by the state’s disparate law enforcement entities. For a fee (which can be waived on proof of low income status), the agency issues individuals with copies of their own official rap sheets. The agency also handles the chore of correcting them. Based in Albany, a small staff at the agency struggles to keep up with problems generated by mistakes buried in its vast incoming data. In 2013, DCJS processed 24,311 requests by individuals seeking to fix their records.

New York’s Office of Court Administration maintains its own set of criminal history records, based on court appearances. Unlike rap sheets, which are based on fingerprint records and can be viewed only by the individual, law enforcement and those employers with statutory authority to do so (who see limited rap sheet information only), the court’s records are open to any member of the public willing to pay a fee. But these records may have their own problems, such as cases that should have been sealed but never were. (See “A Q&A on Rap Sheets”)

And even though official spokespeople for the state’s Office of Court Administration said they were unfamiliar with the issue of errors on criminal history records when queried about them, the office has been wrestling with the problem for many years. At one point, its Criminal Disposition Reporting unit ran a project aimed at reconciling mistakes in its data. More than 727,000 records were corrected before funding for the project ended in 2011.

Last year, officials at DCJS examined cases from 1990 to 2007. It found 415,700 rap sheets included one of the most vexing problems confronted by people—arrests that were missing dispositions. Even though most such cases turn out to have been voided, they appear on paper to be open, active criminal cases. To employers, that raises a major question mark about potential job candidates. “Why would I hire you, or pay money to train you, and then you go to jail?” says Frank Murphy, a paralegal at the Legal Action Center who spends hours tramping through the courts every week in a bid to assist inmates soon to be released from Rikers Island. (See “One Man Vs. a Multitude of Errors”)

And criminal records, mistakes and all, follow people for life. Unlike a number of other states, New York does not expunge, or delete, criminal records. That’s something that many people – individuals with records as well as the general public – do not understand. The common misconception that criminal records somehow disappear after a certain period of time is one encountered often by those who work with people trying to get their criminal history sorted out. Criminal convictions, aside from a few very limited exceptions, never disappear from publicly available records. Likewise, cases that were either terminated in an individual’s favor, or in a noncriminal conviction such as disorderly conduct, also remain on the books, although sealed from public view.

This confusion, between full deletion of records, known as expungement, and suppression, the legal term for sealing a record, often leads to more problems. “Individuals who mistakenly believe their criminal convictions have been expunged and so do not list them on employment applications can be denied jobs on this basis alone,” says Judy Whiting, general counsel for the Community Service Society.

As they stand, state and city laws bar employers from asking about arrests, or taking disciplinary action against workers on the basis of an arrest that did not lead to a criminal conviction. But there’s no protection against being asked about arrests when applying for apartments, loans, or for higher education. As a result, applicants may be denied simply for having been arrested.

Individuals whose cases are churned through the criminal justice system, particularly young people, can be justifiably confused. “They are offered non-criminal offenses as a plea bargain for very minor crimes, like jumping the turnstile, or marijuana possession,” says Alison Wilkey, a lawyer with Youth Represent, about her young clients. “The conduct is so minimal, and it’s their first contact with the criminal justice system. They’re told by their attorney, ‘This is going to seal.'” And the number of potential mixups is huge. In 2013, there were more than 21,000 dispositions of cases involving 16- and 17-year-olds in New York City courts, according to state figures. Statewide, the number was 34,000, about half of them for misdemeanors.

As both Melissa and Juan Carlos Guzman learned the hard way, the system doesn’t always work. Compounding the problem, individuals whose arrests are prosecuted by an overburdened criminal justice system often misinterpret what’s going on, given the rush of courtroom arraignments and adjudications.

“Sometimes people don’t realize they were convicted of a crime when they took a plea,” says Whiting of CSS. She adds that this confusion is not surprising in the city’s bustling arraignment courtrooms, where individuals have often been held in custody for hours and frequently get very little time to discuss their situations with counsel before their arraignment takes place. Others, she notes, wrongly assume the worst about their past arrests. “Not a month goes by when our Next Door Project doesn’t have a client who believes they have a felony conviction on their record when it turns out they don’t even have a misdemeanor,” says Whiting.

‘Hanging’ arrests

Making criminal records even more complicated and error-ridden is a police practice of taking multiple sets of fingerprints from the same individual when they’re taken into custody, sometimes based on the theory that the individual is responsible for a string of crimes. On the law enforcement end, the extra paperwork makes sense: Each alleged crime requires a separate arrest sheet, hence a separate set of accompanying fingerprints, even when they’re taken from the same suspect on the same day.

Briana Duggan

Legal Action Center paralegal Frank Murphy has devoted himself to the tedious, painstaking task of correcting rap-sheet errors.

But since charges are often dropped, or consolidated, it presents a challenge to police and prosecutors to make sure the uncharged crimes are properly voided. That’s where many cases slip between the cracks.

“They’re called ‘hanging arrests’ and they’re a huge source of the problem,” says Kate Wagner-Goldstein, a senior staff attorney at the Legal Action Center. “The police have a confusing procedure. If the DA writes it up as a single complaint, the other arrests are often just left hanging unless someone makes sure to mark them as dropped.”

Frank Murphy, the paralegal at Legal Action Center, spent months trying to sort through multiple such “hanging arrests” listed in the criminal record history of a woman finishing up a short sentence at Rikers Island. At first glance, he says, the rap sheet appeared to show 15 separate encounters with the criminal justice system.

On closer inspection, however, she had only two misdemeanor cases that were actually prosecuted. One of them had been properly adjudicated and sealed as a noncriminal offense, while the other was for the crime for which she was serving her sentence. The 13 additional arrests had all been generated on the same day as the arrest that led to this conviction. All were still listed as open, even though individual cases had never been prosecuted. It took many months, Murphy says, to obtain confirmation that the arrests should have been voided.

Until he sorted it all out, Murphy adds, the rap sheet looked like that of someone the average employer would choose to avoid. “It appeared as though this person, basically, was a career criminal,” he says. “But she wasn’t.”

This story is part of a series by

a class on urban investigative reporting at

the City University of New York Graduate School of Journalism

taught by Errol Louis and Tom Robbins,

who served as editors.

* * * *

3 thoughts on “The Rap-Sheet Trap: Mistaken Arrest Records Haunt Millions”

I have a similar problem in Kansas with my civil record when the courthouse accidentally entered other people’s transgressions on my civil record while I was in college for my second degree. I lost my house and lived in my car for 9 years and 89 days. We need to write a law

permitting mistakes to be corrected but the legislators will not help and I’ve

been told THREE times they won’t until I start giving them campaign donations

like the lobbyist do. The awful details are on my website: UncorrectableGovernmentDatabases.com scroll down to the picture of the Kansas

capitol building for the rant. Norm Crawford

Pingback: » Clips of the Week

I was detained and let go at the police precinct with no charges filed from the D.A but it ended up on my rap sheet and I lost my law enforcement job over this. Can you guys help.