City Limits

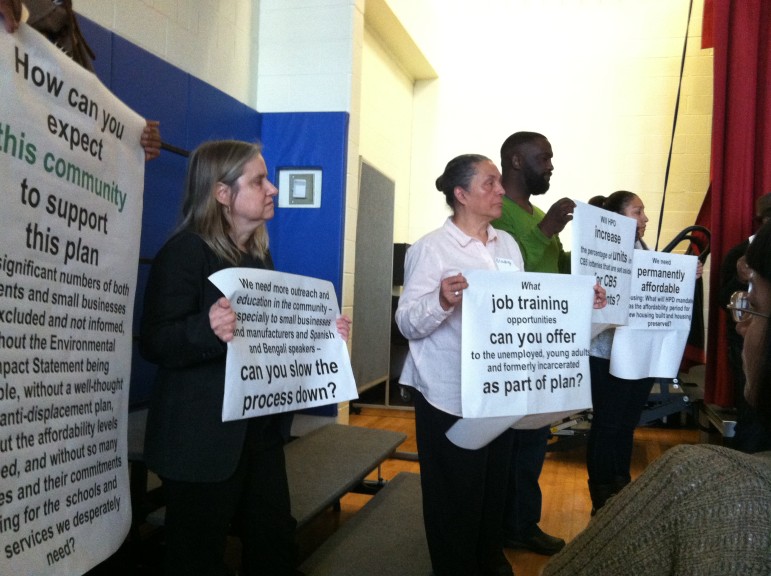

East New York residents presented some of their concerns about the de Blasio administration plans at a recent meeting.

At a Department of City Planning meeting convened in Cypress Hills this January, nine residents marched to the front of the auditorium to face a group of top city commissioners. The residents’ signs, voicing frustration with the city’s proposal to remake the neighborhood, said:

“We need new schools, child care, a community center, health services, more public transit. Where are the service commitments from the agencies not here today?”

“We need permanently affordable housing: What will HPD mandate as the affordability period for housing built and housing preserved?”

“Will HPD increase the percentage of units in CB5 lotteries that are set aside for CB5 residents?”

The protesters, members of the Coalition for Community Advancement, announced they had collected 1,700 signatures on a petition that demanded a guarantee of affordable housing based on the income brackets of the neighborhood and policies to prevent displacement, along with living-wage jobs, the preservation of manufacturing businesses, new schools, early-childhood education and higher-education programs, community centers, green spaces, improved infrastructure and “full participation and input from the community in the planning process.”

A holistic approach to development, guided by community input, is exactly what the city says it wants—and says it has actively facilitated through over 50 meetings with community residents at which it has registered residents’ desires. East New York and Cypress Hills, to its north, are Mayor de Blasio’s first target neighborhoods for affordable housing development and revitalization, and his commissioners know that all eyes are on them to get it right. As DCP Commissioner Carl Weisbrod told the crowd, “This neighborhood is our poster child.”

Yet the Coalition for Community Advancement formed because residents saw the need for discussion outside of the strictures of city-facilitated planning meetings, (where, for instance, officials have tried and failed to control the conversation by having people express their questions silently, on index cards).

In December, in a gathering closed to officials and the press, about 40 residents congregated to begin developing their own vision for East New York. Their diverse mix included concerned residents and representatives from community organizations, local development corporations, churches, small businesses, and block associations.

“We don’t want to be told what we need,” says Darma Diaz, a community organizer with the Coalition. “We want to explain what we need and see how the city can work with us to make that happen.”

The city’s case

The East New York Community Plan has been in the works for a while: DCP began studying the neighborhood’s potential for redevelopment after receiving a grant from the federal department of Housing and Urban Development in 2011, long before de Blasio set his hopes on the neighborhood’s potential for a vibrant, mixed-income community.

At the January 24 meeting, things were starting to get serious. The commissioners of six agencies and their staff had come out to the neighborhood on a snowy Saturday to present the most detailed version of the plan yet to be discussed. The city hopes to commence the Uniform Land Use Reform Procedure (ULURP) in May in order to pass zoning changes that will scale up residential and commercial development.

Through more than two hours of PowerPoint presentations, the city tried to demonstrate its dedication to the community’s interests. Kyle Kimball, president of the Economic Development Corporation, said EDC will collaborate with neighborhood groups to strengthen the Industrial Business Zone. Department of Small Business Services Commissioner Maria Torres-Springer said her agency hoped to establish a more local presence to help connect locals to jobs, target services to Minority and Women-owned (M/WBE) businesses, and support East New York entrepreneurs through programs like Chamber on the Go and Business Acceleration. Other agencies discussed street-scaping and park improvements.

The Department of Housing Preservation and Development explained it plans to use subsidies, tax credits, and mandatory inclusionary zoning to get developers to build rent-regulated housing. Commissioner Vicki Been said that in some of their potential projects, especially at the beginning, 100 percent of the units would be targeted to affordability levels that match the current incomes of neighborhood residents, and that all HPD developments now include set-asides for the homeless.

Yet HPD has not yet specified the specific percentage of units that will be allotted to each income bracket under the inclusionary zoning program, or offered details on the exact types of HPD-supported housing developments that may appear in the neighborhood over the next few years. Given this lack of specificity, many audience members were skeptical. De Blasio’s Housing New York Plan says only 20 percent of units created or preserved under his plan will go to low-income families making less than about $42,000. But such low-income families make up two thirds of East New York’s population, and about 40 percent of East New York families make less than $25,000 a year.

As Andrew Rice reported recently in New York magazine, the announcement of the plan may already be driving up property values and speculative activity. A home that sold two years ago for $160,000 sold last year at $600,000. Brother Paul Muhammad, student director of protocol at Muhammad Mosque 73 and a member of the Coalition, said that he rents a three-bedroom apartment at the reduced rate of $1,991 a month with the help of an HPD program, but has repeatedly received offers from people outside of the neighborhood willing to rent at over $2,500.

Been admitted at the meeting that the revitalization could lead to rising property values that threaten to displace current homeowners and tenants, and that most HPD affordability programs involve loans or tax benefits that only last 30 to 40 years, allowing owners to opt-out of the regulations. But she emphasized the department’s efforts to renew developers’ participation in government-assisted programs, implement code-enforcement programs, inform tenants about their rights and strengthen rent laws. In his State of the City address, de Blasio announced that the city would provide free legal representation to any tenant in a rezoned area that faces landlord harassment.

HPD already has a significant presence in the neighborhood—from managing Mitchell-Lama complexes to allotting $30.3 million in tax credits to a number of developers—and not all residents have been satisfied with its performance.

Pamela Lockley, president of the Linden Plaza Tenant Council, a Mitchell-Lama building in East New York and a participant in the community planning meetings, said that tenants in her building have been repeatedly frustrated by their interactions with HPD. From 2008 to 2010, residents had their rent increased, allegedly to cover the cost of building repairs, by an unprecedented 93 percent over the course of the two years, leading to hundreds of evictions. In 2014, a Supreme Court judge recognized that rents charged by the owners of Linden Plaza were far above the allowable Mitchell-Lama rent increases, and that HPD had erred by signing off on increased rents.

“HPD is going to turn a blind eye to anything that is going to harm the tenants,” she says. “[HPD]’s main goal is to protect that mortgage, and if it means throwing tenants under the bus to help these investors make these millions and billions of dollars, they will do it.”

HPD did not respond to requests for comment regarding Linden Plaza.

In pursuit of the details

“Where was the language: ‘You will have to hire from the neighborhood twenty to thirty percent of the hires from here,’ ‘You will have to use a certain percentage of funds and training to get the people there to become deployed?'” asks Muhammad.

He was among many at the meeting who demanded more specific numbers: specific affordable housing percentages, specific numbers of new schools and jobs. Members of the Coalition say that with details like these still forthcoming, the planning process should be slowed down to allow for more discussion. Coalition member Teresa Toro, a board member of Cypress Hills Local Development Corporation, believes the planning department needs to improve on its outreach to the Spanish and Bengali communities of Cypress Hills.

The city says that both a draft environmental impact statement that assesses the need for infrastructure improvements and schools, and more information about the specific income targets for the city’s affordable housing programs, will be released before ULURP begins. “We’re not hiding anything,” Commissioner Been emphasizes.

Yet with most of the land owned by private developers and with the city refusing to consider the expensive path of eminent domain, there are some elements of the revitalization that will never be known—at least not until the jackhammers start drilling. For instance, while certain rules on hiring practices do apply to businesses that receive a city contract or city subsidy, other private businesses can only be encouraged to hire locally or at a living wage. De Blasio, hoping to make businesses do their part tackling the city’s income inequality and has promised to battle Albany for an increase in New York City’s minimum wage to $13 by 2016.

Melinda Perkins, executive director of East New York Restoration Local Development Corporation, thinks a community-benefits agreement might need to be part of the toolkit for addressing neighborhood demands for resources and good jobs. The LDC is currently managing the community-benefits agreement that emerged from an agreement with the development of phase II of the Gateway Mall; it led to 1,100 local hires and a funding package for Man Up! Inc., which provides job-training and mentorship for at-risk youth.

Joshua Jacobo, a 28-year-old who says he has been through the criminal justice system, has been attending the city’s planning meetings since October. He was frustrated by the city’s focus on the neighborhood’s commercial development and believed that without more programs like Man Up! Inc., new opportunities would remain out of reach to young men exiting prison.

“We don’t even have programs to help these felons to get back into civilized life,” he told the crowd. “They come out to these streets and they have to go right back into criminal activity.”

The city insists that the planning process is far from over and that there is plenty of time—before and after ULURP begins—to think about how to secure community resources. With pressure on the mayor to begin delivering his much-promised affordable housing, it is not likely that the city will want to push back ULURP much longer. From this perspective, residents’ requests to delay the process may run counter to the city’s larger needs—as would Diaz’s request that East New York residents receive priority for a larger set-aside of units than the standard 50 percent.

“Every neighborhood feels like they should have a larger percentage of those units,” says Been. “Every neighborhood in New York City thinks that it has more than their share of whatever.”

Yet Diaz says the Coalition, now at 60 members, plans to take their demands—for more detailed commitments and more time—to City Council committee chairs, their elected officials, and to the public advocate.

Politically charged

In a testament to the way the East New York Community Plan has become the neighborhood’s defining issue of the year, seven of the neighborhood’s former and present political representatives attended the January 24 session, including Councilmembers Inez Barron and Rafael Espinal, Assemblymembers Erik Dilan and Latrice Walker, State Senator Martin Malavé Dilan, Congresswoman Nydia Velázquez and state housing commissioner Darryl Towns.

Councilwoman Barron—who with her husband, Assemblyman and former Councilman Charles Barron, are celebrated by residents for bringing in housing at affordability levels targeted to neighborhood incomes—called for caution.

“You got to be careful with the words that are used. I’ve come to find out that the word ‘perpetuity’ which you would normally think mean forever and ever and ever, doesn’t necessarily mean that. … We have to do a lot of scrutinizing.” She assured residents that she would not support a plan that caused displacement, and told City Limits that if residents feel they need more time to get their questions answered, the ULURP process should be delayed.

Yet Velázquez praised the city for what she said was an unprecedented effort at community involvement.

“I’ve been through this so many times. I represented the Lower East Side. I represented Bushwick, Williamsburg, Greenpoint. … I never witnessed a community-planning process sponsored and lead by a city administration like this one. I have to recognize that our Mayor Bill De Blasio is providing for the community to have a say in this process.”

For all the community meetings on Saturdays in the snow, the multiagency involvement and protesters holding their city’s feet to the fire, will the city really succeed at creating a new model of development—one that includes coffee shops, bike lanes, and the people who lived there to begin with?

Even for Velázquez, there’s not enough information to make conclusions now. “I’m not there yet,” she said. “I need to see the details.”