Adi Talwar

The line outside Bronx Housing Court on a typical morning.

This is the first part in a four-part series on housing court.

To read the whole series, click here.

* * *

The line to get into Bronx Housing Court zig-zagged three blocks to Carroll Place — a steady replenishing stream of about 100 people marching toward the glass doors even an hour past the 9:30 a.m. calendar call.

It was Halloween morning, and moving against traffic was Charles Alexander, who had been in engaged in an animated discussion with his lawyer near the entrance before turning and walking briskly south on the Concourse. He was agitated. His disability benefits, he said, could not cover his rent and he was sick with full-blown AIDS and unable to work. After leaving The Brook shelter in the Bronx, he finally “got me a one bedroom” on St. Ann’s Avenue, he said. Now he was losing his Section 8 benefits because a third-party subsidizer failed to pay their share of the rent.

Still waiting to get inside was Esmerlin Valdez, there for her third appearance on what started as a non-payment case. With help from Bronx Works, a nonprofit occupying the white, castle-like building looming beside the court, she had applied for what’s called a One Shot Deal loan from the Human Resource Administration to pay back what she owed. She was rejected twice, she said, based on a salary she no longer earned, but reapplied and needed more time to hear an answer back. She was afraid that by the time she went back to work full-time, she would no longer qualify for the deal, or that by the time she got help she would already be evicted. Her knees shook constantly.

Landlord attorneys and tenants alike tell tales like these, of tangled bureaucracies that fuel gratuitous litigation even when they are meant to help. But the catch-phrase echoing through the crowded courthouse is always “more time.” It’s the best most tenants are hoping to leave with, and for too many it is a first stop to homelessness.

A three-month City Limits investigation found that tenants in Bronx housing court are at a severe disadvantage facing their landlords in court, not only because legal advice and basic instruction remain elusive for most, but also because the system is overburdened—trying to keep up with a tide of housing need in a borough where rent levels and tenants’ incomes are increasingly mismatched.

An uneven field

The power differential is often exacerbated, rather than equalized, by a civil court that serves as a de-facto debt-collection agency and which processes tenants rather than treating them as equals to the landlords’ attorneys. The attorneys are the ones who regulate the flow of court transactions. And even the most astute pro se litigants get few chances to wage a solid defense. From the landlord perspective, it can seem nearly impossible to get a tenant out of a rent regulated apartment. (Full disclosure: This reporter was in housing court recently over a case which was dismissed.)

Like the Bronx neighborhoods they represent, the tenants are predominantly women of color, often with children, and disproportionately elderly or suffering from serious health problems. Consumer and health-care debt, childcare costs, low-wage jobs, unemployment, and rising rents all show up at doorstep of the courthouse, which falls under the jurisdiction of the New York State judiciary. Those at the mercy of a glitch with their disability check or other benefits or who live on a fixed income and find their rent rising come to Housing Court clutching canes and pushing baby carriages.

The court’s challenge is immense. It is no less than keeping above the tide of human need that the city’s economic evolution is spilling onto its sidewalk every weekday morning.

“Clearly, I think that the system, the housing court system, is flawed in many ways,” says Mitchell Posilkin, general counsel of the Rent Stabilization Association, a trade group for landlords. “The system is flawed because cases are in housing court that shouldn’t be in housing court,” he says. “The system is flawed in the sheer number of cases.”

Caseload leads the city

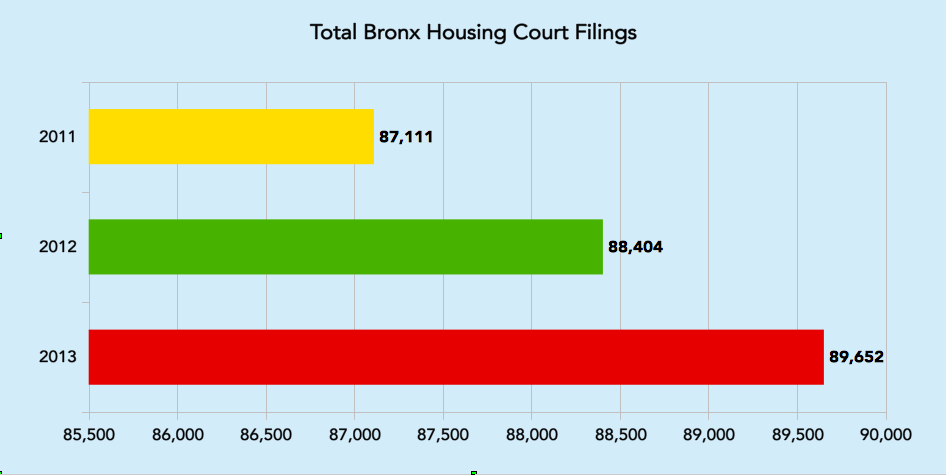

According to reports compiled by court clerks, more petitions were filed in Bronx Housing Court than in any other borough in 2013 — more than 33 percent of the 248,732 filed citywide, though Bronx residents make up less than 20 percent of the city’s population.

Housing Court data

Even as the economic crisis ebbs, the Bronx has seen more disputes head to housing court. That's usually bad news for tenants.

The number of non-payment cases in the five boroughs had been on a fairly steady decline since 1998, according to NYC Civil Court and NYC Department of Investigations data compiled by Housing Court Answers, a nonprofit with a desk in the lobbies of Bronx and Brooklyn Housing courts that provides an array of useful information on the system.

But those cases spiked again from 217,914 in 2012 to 218,400 in 2013, the last full year available. And out of the nonpayment cases filed citywide in 2013, 28,849 led to evictions performed by a marshal, either by default or other judgment.

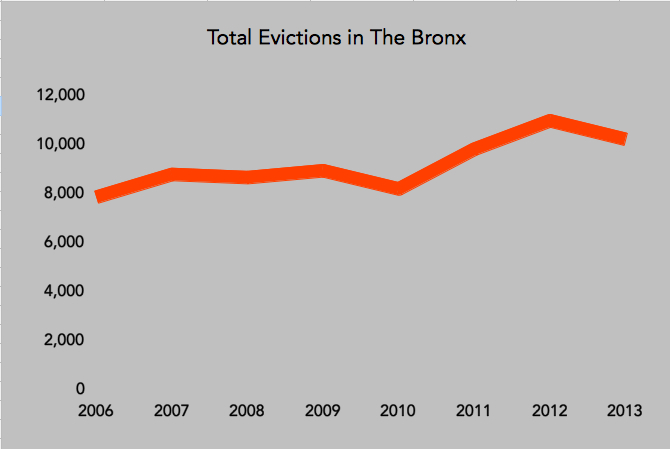

The number of cases resulting in actual evictions by marshals have been steadily increasing since 2006 in every borough, but the Bronx has ranked highest of any borough for evictions each year from 2006 to 2013.

In 2012, 10,966 evictions were ordered in Bronx Housing Court, the highest number any year since 1997 in any borough. While the number fell slightly in 2013, the Bronx still led the city—it was home to roughly a third of evictions citywide—and the borough is on pace to see its eviction numbers climb again when the 2014 data is released.

An economy of plight

Not every court-ordered eviction actually occurs. Organizations such as Bronx Works and Legal Aid routinely intervene and are able to get people back into their homes. Records on how many evictions remain permanent are kept in a way that makes it difficult to track.

DOI

Housing court is on the pathway between the city's overall affordability crisis and the homelessness crisis: families evicted by the court often end up in shelters.

But evictions account for about one-third of homeless intakes, according to the Department of Homeless Services, a growing number that includes a disproportionate share of Bronx families.

While the courthouse serves the entire borough, many who pass through its doors do not come from far. Home Base, a Department of Homeless Services homelessness prevention program, targets Bronx Community District 4 and Community District 1. Housing Court sits in board 4; board 1 is just south.

Perhaps it is oddly convenient, then, that those facing a high risk of homelessness and eviction live in the vicinity of the only stand-alone housing court, which — situated in the shadow of some of the borough’s shiniest beacons, like Yankee Stadium and the Bronx Museum of Art—is the center of its own local economy.

Men peddling cell phone plans spread out pamphlets on plastic tables near the curb. And a guy handing out flyers for free moving and storage service from a company that accepts public assistance views the line as a targeted marketing opportunity.

The firm’s ad is also featured on the food truck right outside the courthouse. It reads: “Evictions. Homeless families. Emergency storage. Public assistance. Domestic violence. Shelter residents. Court orders. Fire victims. Marshal notices,” all watchwords of the crisis that Housing Court oversees daily.

This is the first part in a four-part series on housing court. To read the whole series, click here. The series was made possible through the generous support of the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

This story first appeared on City & State, with which City Limits is partnering to cover crucial housing policies stories in 2015.

* * *

2 thoughts on “Deepening Housing Crisis Plays Out in Bronx Courthouse”

It’s scary how you miss the whole point and that point is there is no “self accountability” in any of this. Not everything is someone else’s fault, the tenant used a service “the apartment” and then didn’t want to pay for it. The LL is not wrong for expecting to be paid and not wanting to shoulder societies problems. Eat at restaurant and then tell them you don’t have money, stay at a hotel and then upon checkout give them your sob story about not having the money and see what happens. LL run a business and I’m so tired of them made a scapegoat be they expect to paid after the provide an apt for someone.

Pingback: Crisis in The Bronx as Residents Being Evicted At Higher Rate Than Any Borough in NYC - Welcome2TheBronx™