NY Fed

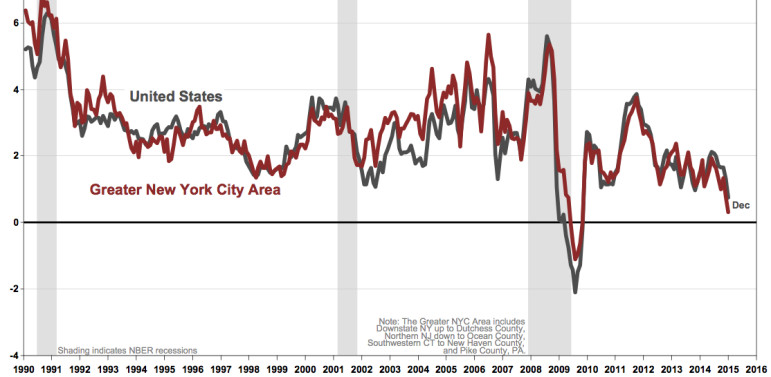

Year-over-year changes to the Consumer Price Index for the U.S. (black line) and the NYC region (red line).

The turmoil over the past few weeks in European currency markets can seem pretty remote from New York City’s economy, which has been adding jobs at a healthy clip. But living as we do in a global financial capital that attracts loads of tourists, you don’t need to resort to chaos theory to wonder if events across the pond could affect prospects here.

In 2011, then-Comptroller John Liu warned of significant “downside risks” to the city from the European debt crisis, mainly because many banks holding lots of debt from struggling Euro countries have a presence in the city. Those risks did not materialize in any obvious way.

But the complexion of the Euro crisis is different now because the very serious problem of deflation, or falling prices, has reared its head in Europe.

Why are falling prices bad? Because people will hold off buying things if they think prices are going to drop further, and because the real value of the debt people owe can swell.

The Euro’s slide is partly a reaction to the steps central bankers over there plan to take to counteract deflation—namely, buying lots of bonds so as to lower interest rates. That’ll put more euros into the economy, reducing their value. Currency investors are trying to get ahead of that by selling euros now, which decreases their worth in dollars.

When the Euro falls against the dollar, U.S. exports become more expensive and it becomes more expensive for Europeans to visit here. The latter effect could have a direct impact on New York City. How big depends on whether the slide persists and how deep it gets.

In the background for New York City is what U.S. central bankers do. The Federal Reserve has signaled it may soon start letting interest rates rise to fight off inflation as the American economy gathers steam. Higher interest rates generally discourage hiring, though it’s not like a linear thing.

What’s striking is the chart above from the New York Fed. It shows growth in the Consumer Price Index, the main measure of inflation. The black line is the U.S. rate and the red line is what’s going on in the broad New York City area. Notice that local prices are growing significantly slower than U.S. prices generally. Also notice that at the end of 2015, price growth was incredibly modest and trending down in a way that it hasn’t since the recession. Falling gasoline prices are likely a big factor in that.

(Vocabulary note here: The chart shows “disinflation” in recent months, or a decrease in the rate at which prices increase. That’s different from “deflation,” which is when prices actually decrease; that occurred briefly in 2009, when the trend went below the zero line.)

Slow price growth is good for workers in some ways: It maintains the real-world value of their salary longer. But super-low inflation also reduces the wiggle room that business owners have to grant raises. And wage stagnation is a problem that many of us know full well the “downside risks” of.