City Limits archives

Koch’s plan created or preserved 180,000 units of affordable housing, a figure the de Blasio agenda aims to beat.

It’s a testament to the endemic difficulty of providing decent housing to New Yorkers that each of the city’s four most important mayors—the ones elected to three terms—are remembered for major housing initiatives. Fiorello LaGuardia built public housing, and so did Robert Wagner. Mike Bloomberg oversaw 165,000 units of affordable housing production and preservation.

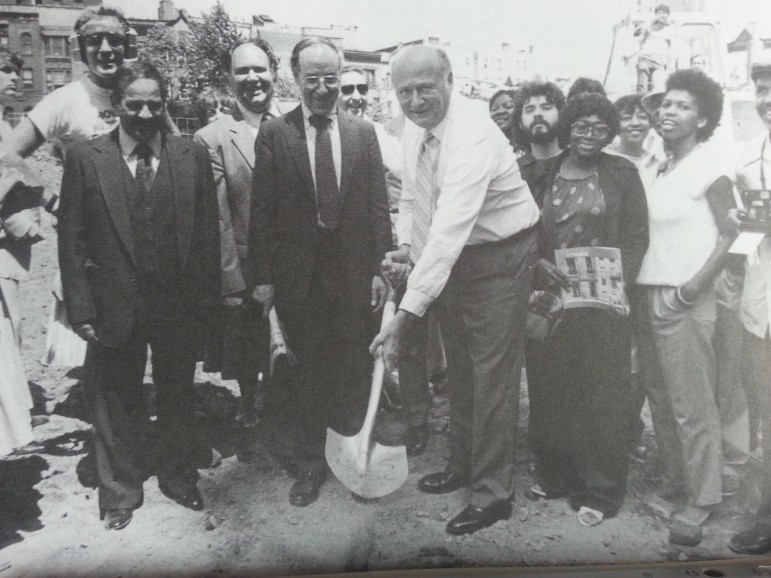

And, of course, there’s Ed Koch, whose 10-year housing plan marked a pivot point in how the city approached housing, and in the history of the city itself.

Where LaGuardia and Wagner channeled generous federal subsidies to create new housing in a growing city, Koch and his many allies figured out a way to capitalize on the city’s 1970s shrinkage and build homes without much federal help. The Koch plan took the massive portfolio of property acquired by the city in fiscal-crisis tax foreclosures and turned it into a resource not just for building housing but also for stabilizing neighborhoods.

As the journalist Wayne Barrett said at a conference Thursday on Koch’s legacy, the new housing was probably as much a part of New York’s dramatic reduction in crime—and subsequent renaissance—as the NYPD’s efforts were.

Bloomberg encountered a different dilemma: how to protect affordable housing in a city with surging population, little federal support and a decreasing inventory of cheap land. We could write a book (and if you’ve got a lucrative advance to dangle, we’d be happy to start on such a tome) about whether the former mayor met those challenges successfully.

But now comes Bill de Blasio. At Thursday’s conference, sponsored by the Association for Neighborhood Housing Development (ANHD), Deputy Mayor Alicia Glen—who helped coordinate the final buildout of the Koch plan while an HPD official in the Giuliani administration—linked Mayor de Blasio’s housing agenda to Koch’s.

“We definitely take a page from the Ed Koch housing playbook,” which, she said, “may have in fact saved out city” by doing more than creating apartments but also “giving New Yorkers hope and doing it in a physical way.” Both Koch and de Blasio, she said, faced the existential question: “What is the future of New York?”

But de Blasio confronts an even stingier federal government, an even smaller supply of available land, vastly changed capital markets, a booming population and the expectation that he can mitigate the affordability and inequality crisis that was his rationale for election.

“The amount of housing we need to build is of an order of magnitude greater than anything we’ve contemplated before,” Glen said. That will require, she said, making affordable housing a condition of all housing development, a reference to the mandatory inclusionary zoning that played out in the Astoria Cove saga.

“When you go down the mandatory route, you better get it right. Because if you don’t get it right, no one is going to build anything,” she added.

Some critics think policies like the ones employed at Astoria Cove will only deepen the affordability crisis because they skew housing production toward market-rate units.

Anticipating that such critics will only grow louder as the de Blasio team fleshes out its plans for East New York, Flushing West, Cromwell-Jerome and elsewhere, Glen implored the advocates and developers in the room not to “throw stones.”

But when the conference turned more fully toward exploring Koch’s legacy, there was a reminder that collaboration is a two-way street.

“When the housing push started aligning itself with communities in planning, that’s when things took off—getting people not just to be sponsors of housing but to get them to really be your partners” recalled Fernando Ferrer, who served as Bronx borough president for virtually the entire length of the Koch plan.

Sometimes this meant the city backing down before anyone picked up a stone—saying to itself, as Ferrer put it, “Maybe that urban renewal plan is no good. Let’s stop the music and do something different.”

One thought on “Koch’s Housing Legacy, Through a de Blasio Lens”

I think that deBlasio’s goal of 200,000 units is unrealistic. Many areas do not want large apartment buildings in their neighborhoods. deB should first find communities that want such large-scale apartment complexes and build there. Less political trouble for him, better chance of getting anything built. But 200,000 will never happen.