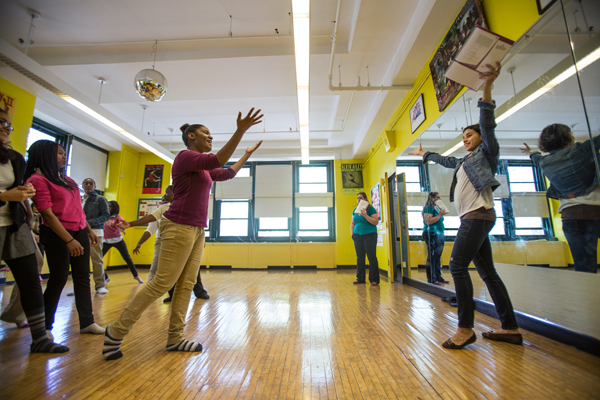

Photo by: Anthony Lanzilote

Students at Ron Brown Academy practice for a performance of “Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory.” The Bedford-Stuyvesant school defies the stereotype that schools in low-income neighborhoods lack arts ed.

Seventy-five 10th graders, who in other schools might ordinarily be texting, flirting, laughing, razzing each other, maybe even giving teachers a hard time, enter Laurie Friedman-Adler’s music classroom at Brooklyn College Academy (BCA) on Coney Island Avenue ready to play—and work. Members of the World Music Ensemble, they spend four days a week learning to play Indian tablas, Japanese taiko drums, African djembes, Native American flutes, Senagalese balaphones, Australian dijerydos, a banjo, a shofar, a harmonium and an Appalachian hammer dulcimer.

These are among the 150 instruments that Friedman-Adler, a professional clarinetist, has collected on travels around the world, and they are the tools for this remarkable orchestra and opportunity for musical development. Every year since 2003, Friedman-Adler and her students have spent a year working on a piece that she composes for a concert in June, melding together all these instruments.

While the World Music Ensemble would be remarkable if it existed in Great Neck, Scarsdale or Montclair, N.J., it is even more so here in New York City since, thanks to a variety of factors, arts and music programs are struggling in the schools, according to arts education advocates.

A combination of forces—budget cuts, the pressure on schools to focus on standardized tests, the elimination of dedicated funds for the arts, the replacement of large high schools with smaller schools with more limited budgets—have worked together to crowd the arts out of many schools. The trend makes a program like Friedman-Adler’s doubly amazing.

Nicholas Mazzarella, Friedman-Adler’s principal, compared her to “the Pied Piper,” and sees what she does as central to BCA. “Lots of schools are dropping arts and music,” he says. “Kids need the arts. Kids in the suburbs get them; our students should get them as well.”

A history of pressure

The erosion of the arts in the New York City schools did not start in the last decade. Before 1975, all community school districts had art and music coordinators and there was an central arts office that provided guidance and support around curriculum. When the fiscal crisis hit, 14,000 teachers lost their jobs and the first ones to go were arts teachers.

While by the 1980’s, many teachers—including arts teachers—were hired back, there is no question that the arts community has always had to make its case for the importance of arts in the schools. “Arts education, long dismissed as a frill, is disappearing from the lives of many students—especially poor urban students,” read a 1993 New York Times story, headlined “As Schools Trim Budgets, The Arts Lose Their Place.” It went on to say that “in New York City, a mecca for artists, two-thirds of public elementary schools have no art or music teachers.”

It was in response to that situation that in 1993 the Annenberg Foundation pledged $12 million to New York City, specifically focusing on the arts, on the condition that the city and other private funders match it two to one. In 1997, Then-mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani, (running for reelection) and the City Council agreed to provide another $75 million over three years. He and the City Council then doubled the arts budget from $25 million to $50 million.

Even more importantly, from this money, the Giuliani administration established a program called Project Arts, in which all principals were allocated $62 per child to be spent specifically on arts education—on teachers, supplies and services by arts-in-education organizations which worked in collaboration with schools. This program of separate funding for the arts continued until 2007 when restricted allocations for the arts were ended by the Mayor Bloomberg’s first schools chancellor, Joel Klein. The move came as the city Department of Education gave fiscal autonomy to individual principals. Arts funding continued to each school, but principals no longer had to spent it solely on the arts and many no longer did.

Doug Israel, the director of research and policy of The Center for Arts Education, a nonprofit established with some of the Annenberg money to restore and sustain arts education in New York City’s schools, calls the elimination of Project Arts and the passage of No Child Left Behind, the 2001 Bush-era federal act which ramped up the focus on high stakes tests in very school, “the perfect storm for arts education.”

“When [the city] eliminated that provision and, federally, the push for accountability focusing on testing in two subjects began, it caused a drastic decline in arts in the schools,” he says.

Today’s picture

National arts education statistics suggest that these days, arts are a persistent—but uneven and thinning—presence in American schools. A 2012 U.S. Department of Education report that compared surveys from 1999-2000 and 2009-2010 found that music was offered in 94 percent of elementary schools during both timeframes, and that visual art offerings dropped only slightly, from 87 percent of schools in 2000 to 82 in 2010.

But dance fared far worse, slipping from 20 percent to 3 percent. And drama went from being offered in one in five schools in 2000, to only one in 25 schools in 2010.

While the growing reliance on standardized tests is a national trend, some believe that city policies have exacerbated pressure on arts in local schools. “It was really local policies—the overemphasis on high states tests, the report card marks, that had the biggest impact,” says Carol Fineberg, a long-time arts consultant who has worked with schools all over the city. “When people are afraid for their jobs, they’re not going to try out new ideas. They’ll muddle along to get along.”

But tests aren’t the only education reform to affect the arts. One of the signature policies of the Bloomberg/Klein administration has been to close large low-performing neighborhood high schools and replace them with smaller schools. Big, neighborhood high schools have traditionally had fine art and photography classes; band, chorus and dance classes. Page through school yearbooks or photographs from as recently as the 1990’s proudly displayed on school walls reveal neighborhood high schools across Brooklyn with choruses, bands and a variety of art classes. Edward R. Murrow High School, the highly successful 4,000-student high school in Midwood, has a renowned arts program with seven music teachers, eight visual arts teachers and five theater teachers.

While small schools clearly have many plusses—not the least among them, offering a chance for teachers to know their students well—they by definition have small staffs and budgets. Students often get just the “basics”: math, English, science and social studies and maybe one language or one art, but many don’t get the “extras” like the a full exposure to the arts, AP classes or other electives.

Kati Koerner, co chair of the New York City Arts in Education Roundtable, a coalition of arts-in-education organizations, says the threat to art today is different from the outright bloodletting during the fiscal crisis. “There is not a massive firing of arts teachers like in the 70’s where all the arts teachers were let go,” she says. “The curriculum is really being narrowed, under the pressure to prepare for tests.”

Working from the DOE’s data, Israel points to the fact that in 2011-12 there are 69 fewer certified arts teachers working in the New York City schools than five years earlier in 2006-7 (2,458 to 2,389) but 304 more schools (1,252 to 1,556 as of 2011-12; more have opened this year and will open in the fall.)

Since 2007, the city DOE has issued an annual “Arts in Schools” report, a survey of principals across the city about arts—visual, music, theater and dance—in the schools, K-12. The most recent report, covering the 2011-2012 school year, paints a complex picture, depending on the grade level, discipline and type of instruction one looks at.

Among elementary schools, for instance, the percentage of facilities offering school-based instruction in the visual arts fell from 82 percent to 77 percent from 2006 to 2012. The share of schools offering school-based theater instruction rose from 26 percent to 29 percent over the same period. But when the scope expands to include art education provided not by teaching staff but by outside cultural organizations, DOE says, 91 percent of elementary kids get visual arts instruction, and 68 percent get theater.

Middle-schoolers, however, get far less art. According to the report, only 12 percent of eighth graders get theater or instruction, 12 percent dance, 29 percent music and a meager 41 percent visual art. In high schools, the offerings grow thinner: Fewer than one in three 10th graders received instruction in visual art.

For Friedman-Adler, the raw statistics don’t encompass what kids are missing. “Eight-five to 90 percent of kids we get in 9th grade never studied music, can’t read music and haven’t learned an instrument,” she says sitting in her room after her students had finished practicing and had put their instruments away. “They don’t know how to hold a pick, they don’t know how to hold the instrument or how to take it out of the closet.”

“These kids are 14 or 15. It’s like students starting to read in 9th grade when other parts around the state—the suburbs—are learning to read in 4th grade,” she says.

Tough choices for schools

Principal autonomy has been a big initiative of the Klein administration. The idea is that the principal should have complete decision-making power on how to spend the money the school receives from the DOE. Some decide to spend some of it on the arts.

Mazzarella, the principal of BCA, not only puts $10,000 into the music program every year for reeds, repairs and other expenses. He, Friedman-Adler and a couple of other teachers constructed a taiko, an immense Japanese drum from a wine cask, nautical cord and skins. “If you have a great person, it’s a no brainer,” he says of his arts spending. “In our case, it’s non-negotiable. BCA wouldn’t exist without the music program.”

World Music Ensemble students also display a deep commitment. Amber Linton, 16, who plays the glockenspiel, got so excited about playing the instrument that she researched it. “It’s typically played in the highest pew of the church so all people could hear it,” she tells a reporter. She also plays the tambourine, as many students play more than one instrument.

Tiara Whitehead, 15, plays one of the taikos, with another girl. “I felt a lot of females don’t get to play big instruments,” she says. “I wanted to show I was as strong as a boy.”

Jeremiah Ayeni, 15, who played a lute-like xiou ruan from China and soloed several times during the class piece, says he had never played an instrument before. “I think it is cool that we all play different instruments and they sound good together.”

The students echo what arts educators have long said. According to Riki Braunstein, who teaches music education at Brooklyn College Conservatory of Music and was a New York City public school music teacher for 25 years, “Studies have shown that students who get an arts education are better students academically. They learn the discipline of practice, the ability to concentrate for a long time, and teach children to get along in a group and depend upon each other.”

But students get more out of it than the individual skills, she says. “Every child needs a hook,” she adds. “Becoming part of a volleyball team, the theatre, working on the high school newspaper. It’s a hook. You get the feeling that, ‘I’m good at this.’ Sometimes it’s the reason you get up in the morning.”

Got art?

Doug Israel estimates that 20 percent of New York City schools do not have an arts teacher or a substantial arts program. Others, like Kati Koerner and Carol Fineberg agree with him “That’s over 300 schools,” he says, “which are equivalent to the number of public and charter schools in the city of Philadelphia.”

But the DOE’s 2011-12 Arts in the Schools report refers to only 75 schools, “whose children had few, if any exposure to the arts,” and adds that the DOE is committed to focusing on and supporting art in those facilities by working directly with their principals.

Paul King, the director of the Office of Arts and Special Projects, the top arts person at the DOE, says some numbers overstate the problem. “It’s not necessary to have a certified arts teacher in the elementary schools. The state only mandates middle schools and high schools to have certified arts teachers,” he says. He adds that the DOE has established a Middle School Committee that is addressing the particular needs and supports for middle schools and will make recommendations this summer.

King acknowledges the pressures that middle schools are under in math and English, the two subjects where standardized tests determine a large portion of the school’s Progress Report. “Schools sometimes have to double up in those areas, making it difficult to program not only the arts and physical education but social studies and science,” he says. He adds that the arts are “a challenge” in co-location sites, where three, four or five schools have to share facilities. But he believes his office can help them figure out ways to share a teacher or a dance space. “We need to do this,” he said.

When King was asked about the 75 schools DOE says offer little or no art, he declined to identify them. “I don’t want to call them out.”

Many assume that these arts-deprived schools tend to be in low income communities, where principals are particularly under the gun to produce higher test scores. According to the DOE report, 100 percent of middle schools on Staten Island offer their students at least one art discipline; only 53 percent of those in the Bronx do.

After all, parents in affluent neighborhoods have long been raising money to supplement the budget—especially in the arts. P.S. 321, the much-admired elementary school in Park Slope, raised $100,000 at a fundraiser two weeks ago, where, according to one attendee, the auctioneer at one point asked, “Who can bid $10,000?” The money raised by parents annually is estimated to be a least $800,000. Principal Elizabeth Phillips says their three music teachers, three visual arts teachers, a dance teacher and more come from a mix of DOE funds and money raised from parents.

However, Ron Brown Academy (MS 57K) in Bedford Stuyvesant defies the stereotype that schools in low-income neighborhoods lack arts ed.

It is a Title 1 School; 76 percent of the students are eligible for free or reduced lunch. Fifteen percent of the population lives in homeless shelters or temporary housing. Eighty percent are black; the remaining 20 percent are Latino.

Celeste Douglas became the principal at the small middle school—it has only 235 students—in 2006. By her own telling, Douglas wasn’t an arts person. “I was more of a technical person. I loved to read and write, but wasn’t that much into the arts,” she says.

When she took over, the school was on the Schools Under Registration Review (SURR) list, meaning it had been cited by New York State as being persistently low performing. There were fights all the time among the students. She and her staff worked on issues around academics but she began to see that it was more than just how they scored on tests.

“I came to realize that the problems the kids were having were that they weren’t connected to themselves and to their community,” she says. “They couldn’t connect to the beauty that exists in the world.”

The school was selected to be part of the School Arts Support Initiative, (otherwise known as SASI) a project of the U.S. Department of Education, the Center for Arts Education and the New York Times Foundation, to fund high-poverty middle schools that previously had little or no arts programming. Ron Brown Academy received $30,000 and Douglas received coaching and professional development on how to integrate arts into her school and write grants.

Douglas went on to win a two-year, $280,000 grant from the 21st Century Foundation and a five-year, $500,000 grant from the Matisse Foundation. The school has an array of arts partners—from TDF’s Stage Doors, which takes students to Broadway plays to Jazz at Lincoln Center, to the Epic Theatre, which introduces the students to Shakespeare.

The grant money pays for extra teachers, tutors who work specifically around arts and literacy, and supplies. But Douglas believes there’ll be a payoff beyond the rehearsal room.

“We not only have an achievement gap, we have an engagement gap,” she says in May as she leads visitors to a rehearsal for the school’s June production of “Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory.”

“Until we realize we have to educate the whole child, until we give them the passion in that the arts do, we’ll always have that gap,” she adds.

Drawing upon art

In a rehearsal room at 3:30 on a Friday about 15 students are rehearsing a song and dance from Willie Wonka, “The Candy Man.” Laura Hill, an English teacher and the director of the musical, is having the groups rehearse bits of the song and dance over and over. After each run through, she gives them some notes and they go through it again. Also on hand are Kristen Crespo, a science teacher and vocal coach, and June Boyd, the dance teacher and the choreographer.

Hill came to the school with Douglas, seven years ago. She had just started teaching through Teach for America and had done children’s theater in Minnesota, where she grew up as a child. She has directed the three musicals the school has done, which have gotten the students involved in a variety of ways—acting, dancing, singing, but also creating props and scenery in art classes, helping put together costumes. They have performed each on Broadway with other schools as part of the Junior Broadway organization.

Arts educators (and Douglas) point to the impact the arts have on kids, even if they are not going to grow up to be an artist themselves.

“Private schools have arts at the center,” says Linda Louis, the coordinator of Art Education at Brooklyn College. “They know there is cultural capital attached to the arts. They wouldn’t dream of not having the arts in their schools. Arts teach you how to make judgments in absence of rules, to tolerate ambiguity and weigh alternatives and pay attention to nuance. These are important aspects of critical thinking and learning that arts provide.”

Out in the hallway at Ron Brown Middle School, a coach from NYU Liberty Partnership, another non-profit that works in the school, is rehearsing five or six other students, including one boy who seems a bit desultory.

“His girlfriend just broke up with him,” confides Douglas. But despite that, he keeps running through the scene.

This sentence has been corrected. The original sentence read: “Before 1975, there was a citywide arts curriculum, which provided instruction in all the grades in visual arts, music, dance and theater.”

This sentence was added for clarity.

This sentence has been corrected. The original article said the DOE’s annual arts survey was self-reported; in fact, it is only partially self-reported.

One thought on “Amid Tests and Tight Budgets, Schools Find Room for Arts”

Pingback: The Music Education Crisis in America | That Tall Guy Over There