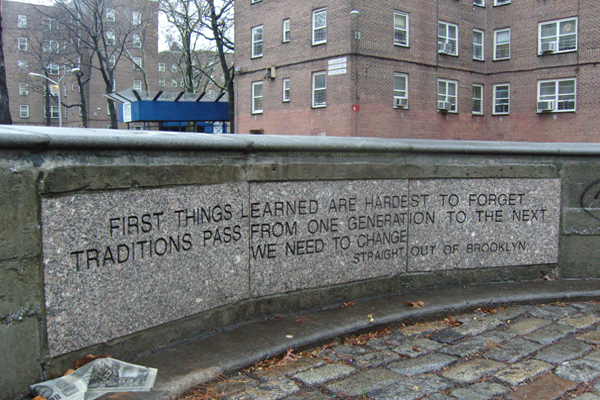

Photo by: Jarrett Murphy

Words of wisdom at the Red Hook Houses, one of more than 300 NYCHA developments that must be operated and maintained on a shrinking budget of federal aid.

The federal government should shift the way it funds public housing, a New York City Housing Authority board member said at a panel discussion of NYCHA’s funding crisis on Thursday.

Federal support for public housing operating expenses has been lagging costs for a decade, costing NYCHA—the nation’s oldest and largest public housing authority—tens of millions of dollars a year. Washington has also shortchanged housing authorities on money for maintenance and repairs, leaving NYCHA with a $6 billion capital backlog.

In the face of those deficits, NYCHA is proposing leasing land at eight public housing developments for private development, hoping to generate lease payments that will cover some of the capital to-do list.

The land-lease approach has been presented as a more realistic option than hoping for a restoration of federal aid, or even counting on Washington maintaining current levels of help.

Emily Youssouf, a NYCHA board member, told a panel at the New School’s Center for New York City Affairs that she thought one way to shore up federal support would be to develop a new form of that aid, in the shape of tax credits.

Right now, Low-Income Housing Tax Credits fund most privately developed affordable housing. The federal government grants the credits to affordable housing developers, and they then sell them to investors who use the credits to lower their tax exposure. The investor gets the tax break, and the developer uses the money from selling the tax break to pay for affordable housing.

Youssouf believes a similar approach could work for public housing.

“One of the problems with rental subsidies is you can’t control the cost of the program and there’s no way to anticipate what those costs are going to be,” Youssouf said. Tax credits would give the feds more control over their costs, while also offering housing authorities the chance to tap into a market for a very popular investment.

“I think it’s clear the federal government is not going to be giving us more money,” she added.

Damaris Reyes, executive director of the Good Old Lower East Side, attributed public housing’s political predicament to the decades-long campaign to paint it as a failure of policy. “The reason we get diminishing support from the feds is because of the negative perception of public housing,” she said. In fact, when it comes to providing a diverse community with an affordable housing option that otherwise wouldn’t exist, NYCHA is a success, Reyes argued.

She added that residents of public housing are suspicious of the land-lease deal because they were excluded from shaping the plan and because they fear that, “Once the get their foot in the door, the developers, they’re going to run free.”

Residents see alternative sources of income, like permitting more retail and commercial development on economically isolated NYCHA campuses, as a way to raise revenue and improve life for residents.

Or, the city could simply stop charging NYCHA $70 million a year for police services. After all, while the feds’ financial withdrawal stings most sharply, New York State (one of only four that built its own, non-federal, public housing) and New York City (the only city to build its own public housing) have stopped year-to-year funding of public housing altogether.